Definition: Acute inflammatory process of the pancreas; a retroperitoneal organ with endocrine and exocrine function.

Epidemiology (Rosen’s 2018)

- US Incidence: 5 – 40/100,000

- Mortality: 4-7%

- Progression to severe disease: 10-15% of cases (mortality in this subset 20-50%)

Pancreas Anatomy (Rosen’s)

Etiology

- Alcohol (~ 35% of cases)

- Gallstones (~ 45% of cases)

- Medications/toxins

- Hypertriglyceridemia

- Non-gallstone Obstruction (i.e. strictures, masses)

- Trauma

- Infectious (Mumps, HIV, Salmonella)

Pathophysiology

- Mild Pancreatitis

- Results from obstruction of the pancreatic or bile ducts or direct toxicity to pancreatic cells

- Inflammation results in pancreatic enzyme activation within the pancreas and ducts

- Premature enzyme activation leads to pancreatic autodigestion

- Moderate Pancreatitis

- Enzyme digestion leads to necrosis of the pancreas

- Erosion into vascular structures can occur as well leading to hemorrhage

- Severe Pancreatitis

- Release of systemic inflammatory mediators

- systemic immune response syndrome and multisystem organ dysfunction (i.e. acute renal failure, cardiac dysfunction, ARDS, disseminated intravascular coagulation)

Presentation

- History + Symptoms

- Abdominal pain

- Typically epigastric but may be RUQ or LUQ

- Will become more diffuse as inflammation progresses

- Rapid onset of pain over a few hours

- Pain is constant, often severe and often radiates to the back (>50%)

- Nausea and vomiting (90%) (Banks 2006)

- Patients often have a history of prior similar episodes

- Dyspnea: Severe pancreatitis can present with dyspnea from diaphragmatic irritation or ARDS

- Abdominal pain

-

Cullen’s Sign

Signs

- Vital sign abnormalities dependent on stage of disease

- Early on may be normal or with slight tachycardia in response to pain

- Later in disease, hypotension, tachycardia and frank shock may develop

- Low grade fever common

- Epigastric tenderness with or without peritoneal signs

- Jaundice: indicates obstruction of common bile duct as etiology

- Hemorrhagic pancreatitis

- Rare complication

- Ecchymosis/discoloration around the umbilicus (Cullen’s sign)

- Ecchymosis/discoloration of the flank(s) (Grey Turner’s sign)

- Vital sign abnormalities dependent on stage of disease

Differential Diagnosis

- Abdominal Pathology

- Perforated viscus

- Peptic ulcer

- Biliary colic

- Cholecystitis

- Cholangitis

- Bowel obstruction

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Cardiopulmonary Pathology

- Acute myocardial infarction

- ARDS

- Pericarditis

Diagnostics

- Basic Diagnostic Criteria (must have at least 2 out of 3)

- Signs/symptoms consistent with pancreatitis

- Lipase elevation: > 3X normal reference range (value depends on lab)

- Imaging (CT scan) consistent with pancreatitis

-

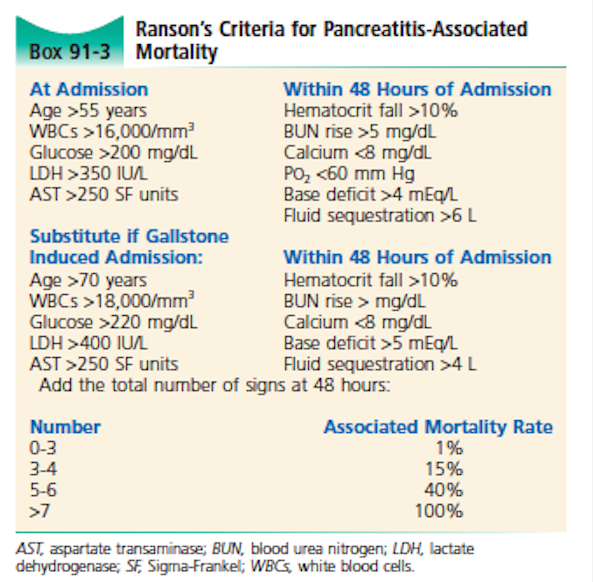

Ranson’s Criteria for Pancreatitis-Associated Mortality (Rosen’s)

Diagnostic Laboratory Tests

- Amylase

- Enzyme produced by pancreas, salivary glands, muscle, intestines and other organs

- Nonspecific marker of pancreatitis as can be elevated as result of various disease processes (Matsull 2006)

- May not be elevated in alcohol pancreatitis (>20%)

- May not be elevated if late presentation (>24h) of pancreatitis (amylase levels return to normal quickly)

- Lipase

- Enzyme more specific to pancreas than amylase

- Specificity: 80-99% depending on where cutoff set (Matsull 2006)

- False negatives may occur early in disease (levels increase in 4-8 hours of onset of inflammation)

- Degree of elevation is not a marker of disease severity

- Triglyceride Level

- Should be obtained in the absence of gallstone or alcohol as the likely etiology

- A level > 1000 mg/dl is suggestive that hypertriglyceridemia may be the cause (Tenner 2013)

- Amylase

- Ranson’s Criteria

- Aids in determining risk of mortality from pancreatitis

- Higher score = greater risk of mortality

- Labs required: CBC, BMP, Hepatic Panel, LDH

-

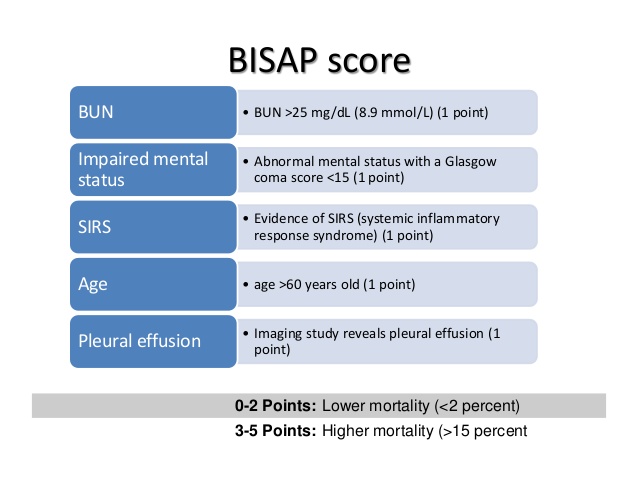

BISAP Score

BISAP Score (Wu 2008, Papachristou 2010)

- Clinical score used to predict mortality from pancreatitis

- Requires less tests than Ranson’s criteria but performs equally well

- Additional Laboratory Tests

- Basic Metabolic Panel (BMP)

- Hepatic Panel

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH)

- Complete Blood Count (CBC)

- Imaging

- Plain Radiographs

- Numerous non-specific findings

- CXR may show pleural effusions, atelectasis or ARDS

- AXR may show an ileus, gallstones, calcified areas of pancreas

- Ultrasound

- Suboptimal imaging modality to diagnose pancreatitis but useful in establishing the presence or absence of a biliary cause

- US superior to CT for finding gallstones and common bile duct dilation (Harvey 1999, Reitz 2011)

- Obtain US as soon as possible

- One study found that US changed management in 55% (6/11) cases (Harvey 1999)

- Converts a medically managed disease to a surgically/interventionally managed one

- High suspicion for biliary disease with negative US should prompt Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP)

- Computed Tomography

- Should not be obtained in all patients with pancreatitis during ED evaluation

- Useful in evaluation of other causes of abdominal pain and for the presence of complications (pseudocyst, abscess, hemorrhagic pancreatitis)

- Which ED pancreatitis patients should get an immediate CT

- Diagnosis of pancreatitis is uncertain

- Presence of severe pancreatitis

- Hemodynamic instability

- Organ failure (Hypotension, ARDS, GI bleed, AKI)

- Ranson score > 3, BISAP > 3 or APACHE > 8

- Concern for early complications

- Plain Radiographs

Management

- Supportive Care

- Intravenous fluids

- Pancreatitis causes 3rd spacing of fluid from the vasculature mainly via increased capillary permeability

- Traditional recommendations for large volume crystalloids (250-500 cc/hr X 12-24 hours) appears flawed (Farkas 2014)

- More conservative resuscitation approaches recommend 2 – 4L of balanced solution over 24 hours

- Give IV fluid boluses as needed for hypotension and volume depletion

- Consider early administration of vasoactive substances if necessary to support blood pressure

- Antiemetics

- Analgesia

- Pain often refractory to traditional analgesics and patients are likely to require opiates

- If patient tolerating oral intake, oral administration of analgesia is appropriate

- Intravenous fluids

- Oral Intake

- Traditional approach discouraged any oral intake and recommended nasogastric tube (NGT) placement

- Recent evidence supports early enteral nutrition (Kahl 2003)

- Recommendations

- If patient tolerates oral intake, start immediately

- If patient does not tolerate oral intake and has continuous emesis, NGT may be useful along with parenteral nutrition

- Antibiotics

- There is no evidence for the use of prophylactic antibiotics in pancreatitis (Tenner 2013)

- Necrotizing pancreatitis without signs of infection does not benefit from antibiotics (Isenmann 2004, Dellinger 2007)

- Antibiotics should be administered to patients with infectious complications from pancreatitis or infectious cause of their pancreatitis (i.e. cholangitis from gallstones)

- Evaluation for Complications

- Pancreatitis is a common cause of alcohol withdrawal. Carefully evaluate patient for signs of withdrawal if they have a history of alcohol use (tongue , tachycardia, hypertension, anxiety etc)

- Cholangitis

- Broad spectrum antibiotics

- Surgical and interventional radiology consultation for drainage

- ARDS

- Gallstone Pancreatitis

- All patients with pancreatitis should have an assessment for biliary pathology

- Presence of gallstones should be treated as gallstone pancreatitis until proven otherwise

- Look for concomitant cholangitis (fever, SIRS, lab abnormalities)

- Consultation

- Consult surgery for possible surgical intervention

- Consult gastroenterology for possible ERCP if biliary obstruction suspected (elevated bilirubin > 5.0 mg/dl) (Tenner 2013)

- Hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis

- Addition of gemfibrozil 600 mg (lipid lowering medication)

- Plasmapheresis (plasma exchange)

- Allows for removal of triglycerides from circulation

- Requires hemodialysis catheter placement

- Insulin therapy

- Reduces triglyceride levels by reducing synthesis and accelerating metabolism

- Dose: 0.25 units/kg/hr (along with a dextrose infusion)

- Plasmapheresis vs. Insulin therapy

- Studies comparing plasmapheresis to insulin therapy are limited (Farkas 2017)

- Plasmapheresis is invasive, more expensive, requires anticoagulation, and requires hematology thus making performance more difficult

- Consider insulin therapy in conjunction with your ICU team

Disposition

- Admission to Hospital

- Any patient with signs or symptoms of severe pancreatitis should be placed in a high-monitored area (ICU) as decompensation is common

- Patients with inability to tolerate oral intake

- Patients with pain refractory to oral medications

- Patients without reliable follow up (i.e. those without insurance, homeless patients, chronic alcoholics etc)

- Patients with gallstone pancreatitis

- Patients who are stable, tolerating oral intake, have their pain controlled with oral medications and are able to follow up or return to the ED may be discharged home on a low fat diet

Take Home Points

- Pancreatitis is diagnosed by a combination of clinical features (epigastric pain with radiation to back, nausea/vomiting etc) and diagnostic tests (lipase 3x normal, CT scan)

- A RUQ US should be performed looking for gallstones as this finding significantly alters management

- The focus of management is on supportive care. IV fluids, while central to therapy, should be given judiciously and titrated to end organ perfusion

- Patients will mild pancreatitis who are tolerating oral intake and can reliably follow up, can be discharged home

Read More

Hemphill RR, Santen SA: Disorders of the Pancreas; in Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al (eds): Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, ed 8. St. Louis, Mosby, Inc., 2010, (Ch) 91: p 1205-1226

PulmCrit: The Myth of Large-Volume Resuscitation in Acute Pancreatitis

PulmCrit: Hypertriglyceridemic Pancreatitis: Can We Defuse the Bomb?

References

Banks PA, Freeman ML. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(10): 2379-400. PMID: 17032204

Matsull WR et al. Biochemical markers of acute pancreatitis. J Clin Pathol 2006; 59:340. PMID: 16567468

Harvey RT, Niller WT. Acute biliary disease: Initial CT and follow-up US vs. initial US and follow-up CT. Radiology 1999; 213(3): 831-6. PMID: 10580962

Reitz S et al. Biliary, pancreatic, and hepatic imaging for the general surgeon. Surg Clin North Am 2011; 91(1): 59-92. PMID: 21184901

Tenner S et al. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(9): 1400-15. PMID: 23896955

Wu BU et al. The early prediction of mortality in acute pancreatitis: a large population-based study. Gut 2008; 57: 1698-1703. PMID: 18519429

Papachristou GI et al. Comparison of BISAP, Ranson’s, APACHE-II, and CTSI scores in predicting organ failure, complications and mortality in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 435-51. PMID: 19861954

Kahl S et al. Acute pancreatitis: Treatment strategies. Dig Dis 2003; 21:30. PMID: 12837998

Isenmann R et al. Prophylactic antibiotic treatment in patients with predicted severe acute pancreatitis: A placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Gastroenterology 2004; 126(4): 997-1004. PMID: 15057739

Dellinger EP et al. Early antibiotic treatment for severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Ann Surg 2007; 245(5): 674-683. PMID: 17457158