Background

- Developed as a bridge for cardiac transplant patients, now also being used as a temporary measure in cardiomyopathies and as a final treatment for those not qualifying for transplant

- Shown to prolong survival in these clinical settings (months to years)

- Can have left VAD, right VAD or both ventricles with separate pump

- Goal is to assist heart function and augment cardiac output

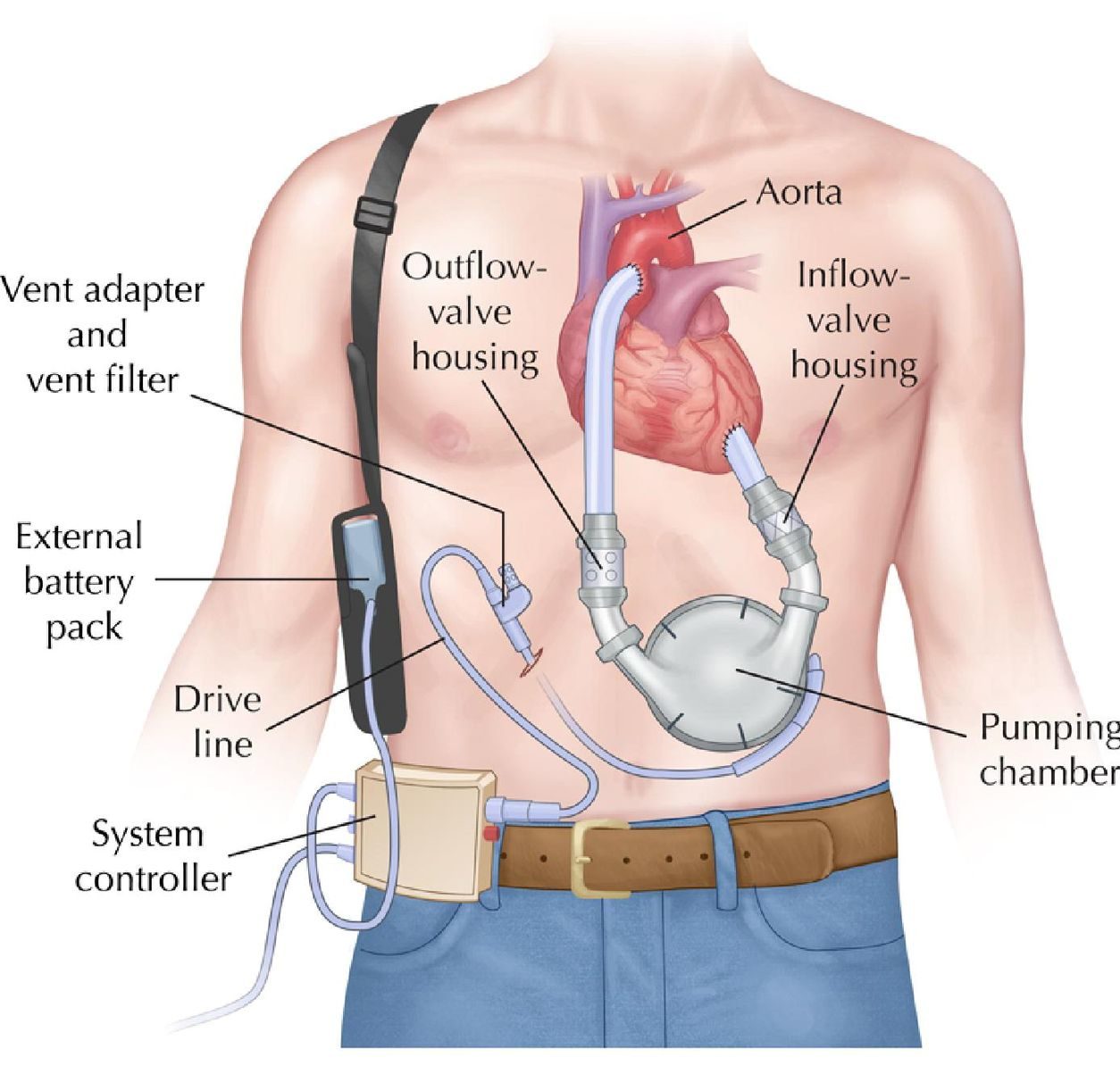

- Components:

- Control box: displays battery power, recent alarms

- Pump: Internal pump, taking blood from ventricle and putting into aorta

- Driveline: connects pumps to external battery and controller (usually out of abdomen)

- Power supply: battery packs and a power base station (at home)

- Large console at LVAD centers: shows power, flow, speed, pulsatility

- These are the major variables that will be set by their cardiologists

1st generation: pneumatic pump → pulsatile blood flow

(Wilson 2009)

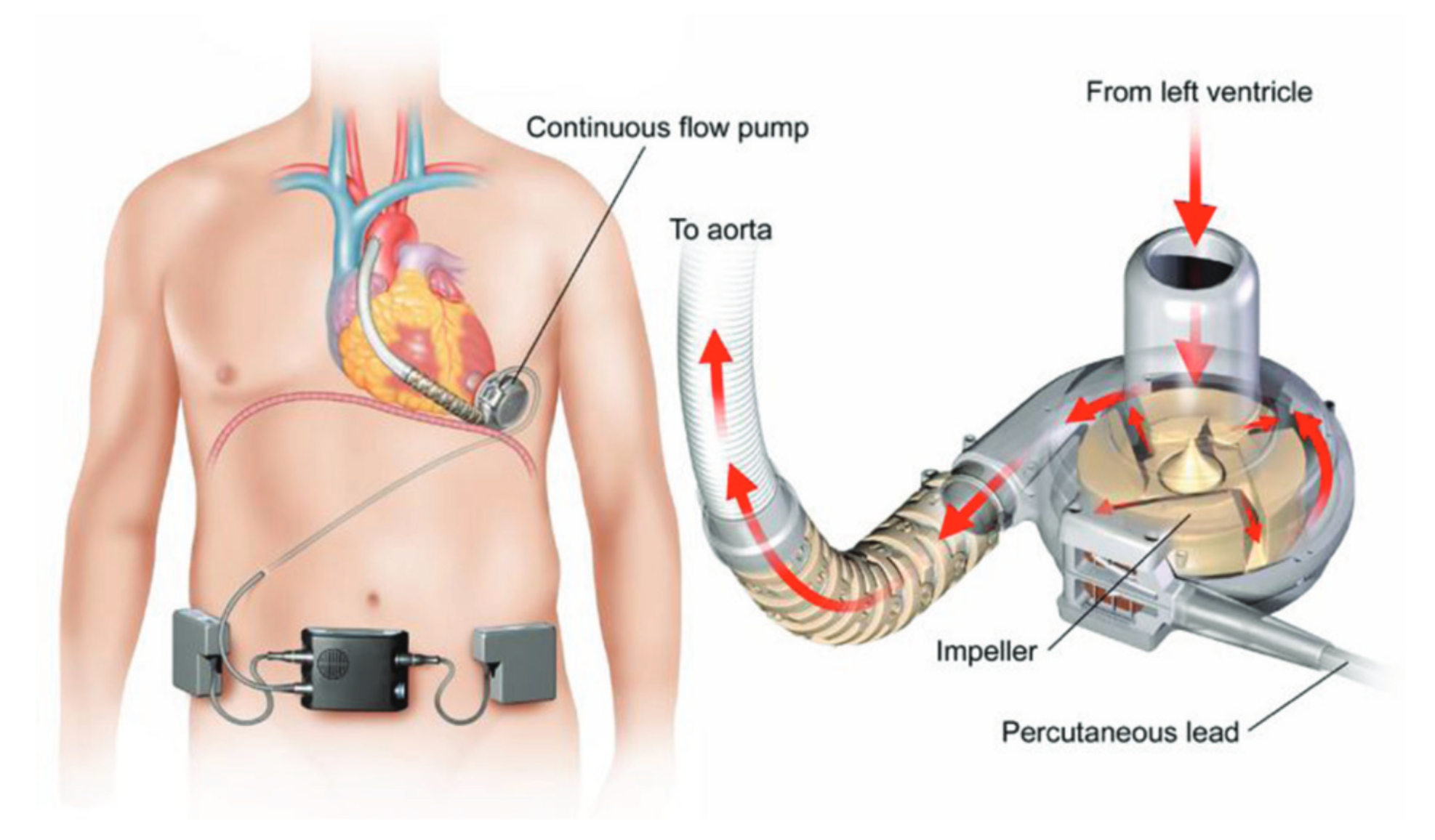

2nd generation: centrifugal/axial flow pump → continuous flow

- Directly connected to patients LV (lies above the diaphragm within the pericardium)

- Blood back to ascending aorta by separate outflow cannula

- Advantages to 1st generation:

- Smaller size

- Increased durability

- Increased efficiency

- Decreased thrombogenicity

(Aaronson 2012)

General Management

- Contact the LVAD team immediately

Focused History

- Type of device, placement date, previous complications (most devices have this information on it or the patient should know)

Physical exam

- With continuous flow devices, the patient will not have a pulse!

- Blood pressure

- Obtain a manual cuff and arterial doppler device – find brachial or radial artery

- Inflate manual cuff until arterial flow cant be heard, then release; MAP is recorded when arterial flow returns through doppler

- Target MAP Is 70-80 mmHg, max of 90

- Can also monitor with a-line in more critical situations

- Pulse oximetry: may not be accurate if no pulsatile flow – consider obtaining ABG if concerned for respiratory issues

- Cardiac exam: a “hum” should be heard, check for JVD or pulmonary edema (signs there may be right heart failure)

- Power cord: from abdomen usually, evaluate for infection

Diagnostics

- Labs: CBC, CMP, PT/PTT/INR, LDH, haptoglobin, TEG (if available), LDH, BNP, troponin, UA, T&S

- EKG should be performed

- CXR: To evaluate for signs of heart failure, cardiomegaly, pulmonary edema, PNA, driveline damage

- POCUS: LV and RV function, signs of RH strain may signify pulmonary hypertension or a PE. Overdistended LV may indicate pump malfunction, thrombus or severe aortic regurgitation. Check for pericardial effusion or tamponade as well.

Complications and Management

Always consult patients LVAD team!

Bleeding:

- Etiology:

- Usually from supratherapeutic INR (patients are usually on coumadin, antiplatelet therapy with INR goal of 2-3)

- AV malformations

- Acquired von Willebrand disease from pump shear forces

- Signs

- GI bleeding

- Epistaxis

- Intracranial hemorrhage

- Pericardial tamponade /effusion

- Treatment

- Reverse with FFP or PCC (for INR, treat until back to 2-3 to avoid clotting in pump)

- DDAVP or cryoprecipitate (vWD)

- Consider TXA

- Platelet transfusions

- Vitamin K

Infection

- Etiology

- Sepsis

- Pump endocarditis

- Driveline infection

- Signs

- Can result in low flow, hypovolemia

- Most common cause of death (usually within 3 months of placement)

- Treatment

- Antibiotics (cover for MRSA)

- Fluids as needed

- Obtain US/CT to evaluate abscess/collection

Thrombosis

- Can see in 2-35% of patients, suspect in any arrest or cardiogenic shock or decreased flow

- Evaluation

- Knocking sound on cardiac exam can be sign of rotor thrombus

- POCUS: Overdistended LV with shift of septum indicates blockage and can possibly see hypoechoic mass near inflow cannula

- Labs: elevated LDH, hemoglobinuria

- Treatment

- Anticoagulation with a continuous heparin infusion and antiplatelet therapy

- Consider tPA in life threatening situations

Arrhythmia

- Primary – Intrinsic to heart

- Ventricular arrhythmias are common from scarring

- SVT and ventricular tachycardia can be common

- Cardiac output is from the LVAD and not the heart ∴ the patient should have no signs or symptoms if they are VAD-dependent

- Secondary

- Can occur if LV septum/free wall are sucked into conduit vs hypovolemia

- Difficult to distinguish

- Can occur if LV septum/free wall are sucked into conduit vs hypovolemia

- Treatment:

- Prompt fluid challenge

- Emergent bedside echo

- RV failure and reduced LV filling occur if primary arrhythmia not treated

- Manage with cardioversion if unstable or antiarrhythmic meds (amiodarone vs. lidocaine vs beta blockers [no specific choice])

- Use standard ACLS energy recommendations

- Do not place defibrillator pads over the driveline

Stroke

- Risk increases with MAPs >90 (ischemia and hemorrhage)

Pump failure

- Inability to detect MAP

- No sound on exam

- May be due to control box malfunction

- Treatment

- IVF

- Standard ACLS with epinephrine drip, heparin drip

- If suspicion of clot consider VA ECMO early

- If no response after 1 minute of above (fluids, epinephrine) CPR can be initiated (more below)

“Suckdown”

- Occurs when patient’s septum or other part of heart is entrained into inflow cannula

- Etiology

- Decreased LV (from RV failure) volume

- Cardiomyopathies

- Arrhythmias

- Cannula migration

- Hypovolemia

- Tamponade

- Signs

- Hypotension

- Syncope

- Arrhythmias

- Treatment

- Decrease RPM rate

- IVF

Cardiac arrest

- Avoid CPR at all costs if possible, it can theoretically dislodge the LVAD

- Some first generation LVADs have hand pumps that can help with circulation

- Evaluate for other causes of pump failure before doing compressions (i.e. thrombus, battery)

- Check alarms, check the power. Call LVAD team!

- If no flow, no hum, no MAP detectable, and the patient has not responded to any other measures, start ACLS like normal as a last ditch effort (i.e. start compressions and perform CPR)

Take Home Points

- Always contact patient’s LVAD team to assist in care

- Ensure controller is powered on and has backup battery

- BP obtained with doppler, MAP should be between 70-90. Many will not have a pulse.

- If hemodynamically unstable, try fluids first; LVADs are preload sensitive

- If concern for thrombus, use tPA in emergencies

- For cardiac arrests, evaluate for pump failure and then move to ACLS if epinephrine gtt unsuccessful

Resources

- Aaronson KD, Slaughter MS, Miller LW. Use of an intrapericardial, continuous-flow, centrifugal pump in patients awaiting heart transplantation. Circulation 2012 June 26, 125 (25): 3191-200

- Mancini, D. Practical management of long-term mechanical circulatory devices. UpToDate. Mar, 2018. Link: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/practical-management-of-long-term-mechanical-circulatory-support-devices

- Winters M, et al. Emergency Department Resuscitation of the Critically Ill. Second Edition. Texas: American College of Emergency 2017: p145-154.

- Miller LW, Pagani FD, Russell SD, et al. Use of a continuous-flow device in patients awaiting heart transplantation. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:885-896. PMID: 17761592

- EM:RAP. Episode April 2019, Chapter 9

- Tintinalli, Judith E., et al. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. Eighth edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2016: Section 7: 382.

- Sen, A., Larson JS., Kashani, KB., Libricz SL, Alwardt CM, Pajaro O., et al. Mechanical circulatory assist devices: a primer for critical care and emergency physicians. Critical Care, 2016 Jun 25; 20(1): 153. PMID: 27342573