Case:

86-year-old female with a past medical history of CHF and O2-dependent COPD is brought in by EMS for acute onset abdominal pain in the setting of 10 days of diarrhea. On arrival, T 38, HR 160, BP 70/50, RR 30, SpO2 87% on room air and her exam is notable for a rigid, distended abdomen. You are able to stabilize her with IVF, supplemental O2, and antibiotics. The CTAP demonstrates toxic megacolon with associated pneumoperitoneum. Surgery is urgently paged. The patient is intermittently confused but you are able to gather from her that she has no advanced care directive or health care proxy form.

Palliative Care (PC):

- Definition: An approach dedicated to improving the quality of life of patients and their families who are facing life-threatening illness.

- It involves preventing and alleviating physical, emotional, social, and spiritual components of suffering as well as communication strategies focused on eliciting and discussing goals of care.

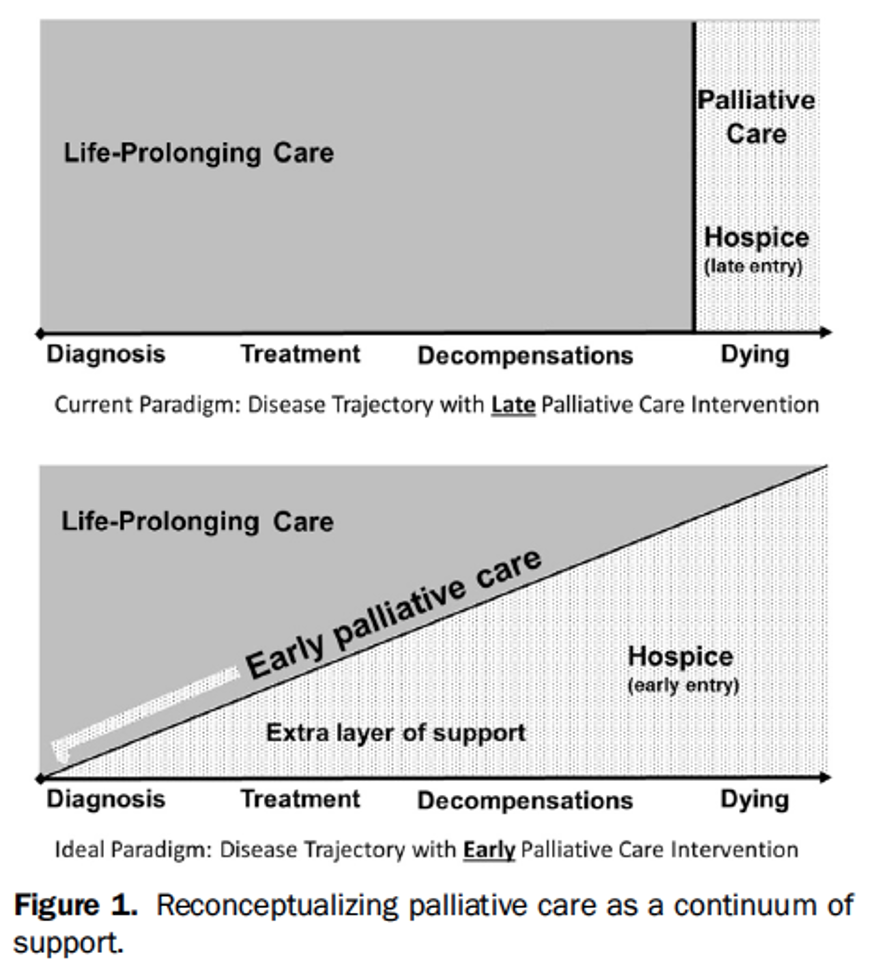

- It is important to know that palliative care may be provided while a patient is still receiving disease modifying therapy (e.g. chemoradiation, surgery, dialysis).

Hospice:

- Definition: Hospice care is palliative care in the last 6 months of life and is focused primarily on managing symptoms and providing comfort.

- Palliative care can be provided alongside curative care; however, hospice is only offered when life prolonging care is no longer beneficial and treatment goals are instead focused on symptom management.

- Hospice service is paid for by Medicare for most patients, whereas palliative care is typically covered by private insurance.

Palliative Care in the ED:

- As demonstrated by the case above, patients frequently present to the ED with complications of their underlying advanced cancer, dementia with multiple comorbidities, severe or incurable neurological conditions, or other organ failure.

- A longitudinal study conducted from 1992-2006 followed 4518 patients 65 years or older and found that more than half of these patients visited the ED in the last month of life and 75% visited in the last six months (Smith et al 2012).

- ED physicians are uniquely positioned to intervene on behalf of this vulnerable patient population and discuss goals of care in these critical moments, in addition to connecting these patients expeditiously with palliative care services. By doing so, we can promote care that aligns with patients’ goals and the avoidance of potentially unwanted, resource intensive interventions.

- Palliative care is typically thought of as a specialty service; however, it can also be provided by other providers – this is known as primary palliative care. In fact, primary palliative care skills are considered core competencies for emergency medicine physicians.

- ACEP has developed a quick guide for practicing palliative medicine in the ED.

- As part of the Choosing Wisely Campaign, ACEP has recommended to avoid “delay[ing] engaging available palliative and hospice care services in the emergency department for patients likely to benefit”.

PC Skills as Part of the ED Toolkit:

- EM physicians must be comfortable with basic primary palliative care which includes the ability to discuss goals of care with the patient and their family to provide the care most beneficial and desirable for the patient in time-sensitive situations.

- As emergency department providers, we have seen chronically ill patients receiving a full array of resuscitation efforts because we did not pause to search for an advanced care directive, reach out to a longitudinal provider, or speak to a family member about how this patient would wish to live or die. Too often, we simply follow our resuscitation algorithms without thinking critically about the risks and benefits of our interventions and whether or not these actions are aligned with the patient’s goals.

- Although the resuscitation of a critically ill patient is central to the practice of emergency medicine, we must learn to pause before aggressive interventions in the patient with advanced illness. We ought to put the patient, their autonomy, and their goals back into the center of our practice.

- Briefly, a “pause” in the resuscitative efforts may include:

- The initiation of interventions such as supplemental O2, BIPAP, IVF resuscitation that may offer a few minutes to quickly investigate the patient’s goals of care.

- If possible, designate a member of the team to chart review to rapidly locate documentation within the electronic medical record or alternatively, this team member should ask the person accompanying the patient if they have any knowledge of or access to these documents. If no documentation is available, quickly assess goals of care with the appropriate decision maker. See this great resource from ALiEM for tips on how to lead this conversation.

- If there is no formal documentation, the appropriate decision maker is not available or the patient’s mental status prohibits shared decision making, it is appropriate to proceed with the clinically indicated emergent measures to stabilize the patient, followed by reaching out to family members and/or additional resources including the palliative care team for assistance.

Benefits for our Patients:

- Early initiation of palliative care has been associated with improved quality of life and extended survival by 3 months, despite receiving less aggressive care at the end of life.

- In patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer randomly assigned to standard care vs early palliative care, the latter reported better quality of life, fewer depressive symptoms, and demonstrated longer median survival of approximately 3 months (Temel et al. 2010).

- Avoidance of undesired interventions with enhanced patient autonomy.

- Focus on patient centered outcomes with aggressive symptom management that is associated with improved satisfaction with care, as reported by patients and families.

Benefits for EM Providers & the Hospital System:

- Nearly 65% of EM physicians reported burnout in a 2017 survey placing EM physicians at particularly high risk for depersonalization and subsequent compassion fatigue. Palliative care’s focus on patient engagement and compassion helps to place patients back at the center of our practice. This in turn, can help protect against this emotional exhaustion when caring for patients.

- Connecting patients with palliative care and/or hospice services allows for more appropriate resource utilization.

- One study found that expedited palliative care engagement led to a 50-75% reduction in both length of stay (on average 4-5 days) and cost when compared to typical inpatient consult initiation (Wang et al. 2020).

Indications for Emergent PC Involvement in the ED:

- If you answer “no” to the question “would you be surprised if this patient died during this hospitalization?”

- Assistance with clarifying goals of care in patients with serious life-limiting illness with acute complications.

- Advanced symptom management including pain, nausea and shortness of breath.

- Decline in patient’s ability to function, decline in weight, inability to eat/ drink (aka failure to thrive) in the setting of a serious life-limiting illness.

- Previously enrolled with a hospice service.

- Acute catastrophic event including out-of-hospital cardiac arrest or an acute devastating neurologic injury.

Hospice Referral from the ED:

- Referral should be placed for a patient with a prognosis of less than six months when disease modifying therapies are no longer beneficial or when the patient’s goals are focused on comfort.

- UCSF has formulated an easy-to-use algorithm to help physicians estimate prognosis for patients using functional and lab data. This has primarily been validated in patients with cancer and clinical judgement should be used in other illnesses.

- Notably, a palliative care consult does not need to be obtained in order to refer to hospice services. Case managers and social workers in the emergency department are typically able to complete the enrollment process.

Case Conclusion:

Ms. Cooper is seen by surgery who recommends an emergent exploratory laparotomy and bowel resection. You initiate a brief goals of care discussion. She states that she is willing to have the operation, however, she opts to have a “do not resuscitate” (DNR) order following the surgery. She also designates her brother as her health care agent. She undergoes surgery and is admitted to the SICU. She is extubated on POD #2, however she soon develops ventilator associated pneumonia causing respiratory distress. The inpatient palliative care team meets with the patient who elects to not be intubated in addition to her DNR. She develops worsening respiratory distress. Her brother decides to transition goals to primarily comfort measures. Small doses of morphine are used to alleviate her dyspnea and she is transitioned to the inpatient hospice unit.

Take Home Points:

- Palliative care focuses on preventing and treating all forms of suffering in patients experiencing a life-threatening illness. Hospice care is a form of palliative care that applies to patients in the last six months of life, when patients are no longer receiving disease modifying therapy.

- Patients frequently present to the ED in the last six months of life and would benefit from palliative care (provided by ED physicians or palliative care specialists) regardless of their stage of illness or current interventions in order to provide patient-centered goal-concordant therapy.

- In accordance with ACEP’s Choosing Wisely Campaign, if you believe a patient may benefit from the involvement of palliative care, err on the side of obtaining the referral on behalf of your patient.

References:

Denny, S. (2020, December 10). Palliative medicine. Retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://wikem.org/wiki/Palliative_medicine

May, P., Normand, C., Cassel, J. B., Del Fabbro, E., Fine, R. L., Menz, R., Morrison, C. A., Penrod, J. D., Robinson, C., & Morrison, R. S. (2018). Economics of Palliative Care for Hospitalized Adults With Serious Illness: A Meta-analysis. JAMA internal medicine, 178(6), 820–829. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750

Meier, D. E., MD. (2020, June 12). Benefits, services, and models of subspecialty palliative care. Retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/benefits-services-and-models-of-subspecialty-palliative-care

Meier, D. E. (2020, December 7). Hospice: Philosophy of care and appropriate utilization in the United States. Retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/hospice-philosophy-of-care-and-appropriate-utilization-in-the-united-states

Mierendorf, S. (2014). Palliative Care in the Emergency Department. The Permanente Journal, 18(2), 77-85. doi:10.7812/tpp/13-103

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America. Alexandria, VA, Released September 2017. https://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2016_Facts_Figures.pdf

(Accessed on 12/10/2020)

Quest, T. E. (2020, August 17). Palliative Care and Emergency Department. Retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://www.capc.org/toolkits/integrating-palliative-care-practices-in-the-emergency-department/

Quest, T. E., Marco, C. A., & Derse, A. R. (2009). Hospice and Palliative Medicine: New Subspecialty, New Opportunities. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 54(1), 94-102. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.11.019

Smith, A. K., McCarthy, E., Weber, E., Cenzer, I. S., Boscardin, J., Fisher, J., & Covinsky, K. (2012). Half of older Americans seen in emergency department in last month of life; most admitted to hospital, and many die there. Health affairs (Project Hope), 31(6), 1277–1285. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0922

Schenker, Y., MD. (2020, March 5). Primary Palliative Care. Retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/primary-palliative-care

Tan, A., DO, & Krafchik, B., MD. (2019, July 23). What is palliative emergency medicine and why now? What is palliative emergency medicine and why now? Retrieved January 20, 2021, from https://www.aliem.com/palliative-emergency-medicine-what-why/

Temel, J. S., Greer, J. A., Muzikansky, A., Gallagher, E. R., Admane, S., Jackson, V. A., Lynch, T. J. (2010). Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 363(8), 733-742. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1000678

Twaddle M.L. (2012) Palliative Care and Hospice: Advancing the Science of Comfort, Affirming the Art of Caring. In: Harrington J., Newman E. (eds) Great Health Care. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-1198-7_21

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care

Wang DH, Heidt R. Emergency Department Admission Triggers for Palliative Consultation May Decrease Length of Stay and Costs. J Palliat Med. 2020 Sep 8. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0082. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32897797.

Wang, D. H. (2017). Beyond Code Status: Palliative Care Begins in the Emergency Department. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 69(4), 437-443. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.10.027