Definition:

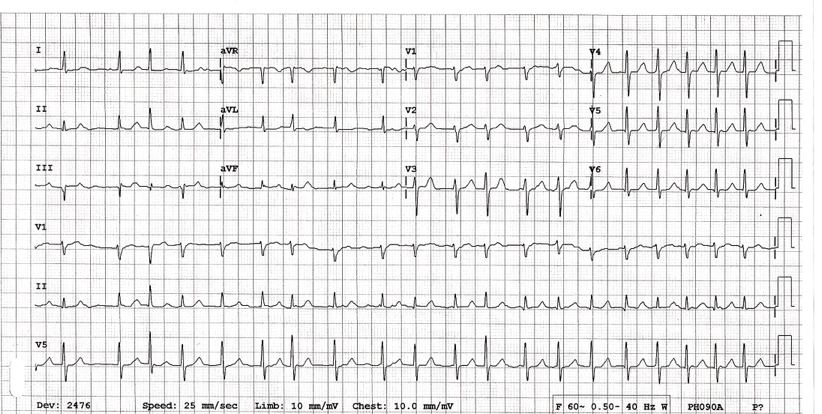

Atrial Fibrillation (AF): Dysrhythmia resulting from depolarization of multiple microreentry circuits. These circuits bombard the AV node with 300-600 atrial impulses per minute. Due to the refractory period of the AV node, this chaotic electrical activity is intermittently transmitted down the conduction system resulting in the hallmark “irregularly irregular” ventricular response (up to 150-170 beats/minute)

Recent-Onset: Typically defined as atrial fibrillation that has been present for < 48 hours.

Lone AF: Isolated AF without another underlying process (see causes below)

Differential to Consider

- Atrial Flutter with Variable Conduction

- Multifocal Atrial Tachycardia (MFAT)

- Multiple Extrasystoles

- Wandering Pacemaker

Causes of AF

- Congestive heart failure (CHF)

- Structural causes: Valvular heart disease, Cardiomyopathy

- Endocrine disorders: Hyperthyroidism, pheochromocytoma

- Drug & Alcohol: stimulants, amphetamines, acute alcohol intoxication (aka “Holiday Heart”)

- Catecholamine excess

- Cardiac surgery

- Sick sinus syndrome

- Cardiac ischemia

- Inflammation: Myocarditis, Pericarditis

Effects of Atrial Fibrillation on the Heart

- Prolonged atrial fibrillation leads to cardiac remodeling and can lead to cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure

- Atrial Clot Formation

- During atrial fibrillation, the atria do not contract effectively resulting in stagnation of blood in the atria (particularly the left atrial appendage)

- After 48-72 hours of atrial fibrillation, the risk of clot formation is significant

- Clot formation in the left atrium increases the risk of systemic embolization

Basics: ABCs, IV, Cardiac Monitor and 12-lead EKG

Directed Management

- Establish patient stability

- Unstable AF

- Defined as the presence of hypotension or hypoperfusion of end organs (i.e. presence of ischemic cardiac symptoms, altered mental status)

- Unstable patients should be considered for immediate electrical cardioversion regardless of duration of dysrhythmia

- Stable AF

- Area of active debate within EM

- Case for rate control (Decker 2011)

- Case for rhythm control (Stiell 2011)

- Unstable AF

- Determine whether the AF is in response to another underlying process (see causes above) or is simply lone atrial fibrillation. In patients where AF is a response to another underlying process, management should be directed at treating the underlying process NOT at the dysrhythmia. (Atzema 2015)

- Establish time of onset of symptoms

- Patients with clear onset of symptoms < 48 hours prior to presentation are candidates for cardioversion (electrical or chemical) to sinus rhythm in the ED without an echo to confirm absence of left atrial clot

- Patients with a vague history of onset of an onset > 48 hours prior to presentation who are not already effectively anticoagulated should not be considered for rhythm control without a transesophogeal echo to rule out clot in the left atrium

- Rhythm Control

- Goal: Convert patient from AF to sinus rhythm using either chemical agent or electricity

- The longer a patient is in AF, the more difficult it is to convert the patient out of the rhythm.

- Chemical Cardioversion

- Procainamide

- Dose: 18-20 mg/kg IV (administer 30-50 mg/min)

- Conversion rate: 60% success rate

- Monitor patient for QT and QRS prolongation and hypotension

- Amiodarone

- Dose: 3-5 mg/kg IV over 15-20 min

- Conversion rate:

- ~ 60%

- Delayed efficacy (Chevalier 2003)

- No benefit at 1 or 2 hours post-administration vs placebo

- Increased conversion rate vs placebo at 6-8 hours

- Complications: Hypo/Hyperthyroidism, pulmonary fibrosis

- Ibutilide

- Dose: 0.015 – 0.02 mg/kg IV over 10-15 min

- Typically successful w/in 20 minutes if it works

- Procainamide

- Electrical Cardioversion

- Electricity administration: synchronized cardioversion with 100-200 J (biphasic)

- Stable patients should receive concomitant procedural sedation and analgesia

- Multiple studies demonstrate safety of electrical cardioverion (Michael 1999, Stiell 2010, Scheuermeyer 2010 Coll-Vinent 2013)

- Ottawa Aggressive Protocol (Stiell 2010)

- Pathway for management of recent-onset AF with goal of cardioversion

- See Core EM Journal Update Post for further details

- Rate Control

- Goal: Reduce rate of ventricular response to a target number (< 110) (Van Gelder 2010)

- Standard therapy is with an AV nodal blocking agent (beta-blocker or calcium channel blocker)

- Beta Blocker

- Metoprolol: 0.15 mg/kg (max of 10 mg) IV push

- Contraindications: Active reactive airway disease (i.e. asthma), acute decompensated heart failure, drug sensitivity

- Calcium Channel Blocker

- Diltiazem: 0.25 mg/kg (max of 30 mg) IV push

- Verapamil: 0.25 mg/kg (max of 30 mg) IV push (CONFIRM DOSING)

- Contraindications: Acute decompensated heart failure, drug sensitivity

- Preferred agent in the ED

- It is unclear from the current available data whether a beta blocker or calcium channel blocker is the preferred agent for rate control

- A small (n=40) randomized, non-blinded study demonstrated equal efficacy of metoprolol + diltiazem but faster rate control with diltiazem (Demircan 2005)

- A more recent small (n = 54) randomized, double-blinded study demonstrated more rapid rate control with diltiazem than with metoprolol at 30 min (95.8% vs. 46.4%) (Fromm 2015)

Note: Recent-onset atrial flutter is treated similarly to recent-onset atrial fibrillation.

Anticoagulation

- Patients with paroxysmal or permanent AF are at increased risk for systemic embolism and stroke

- All patients with AF should be evaluated for systemic anticoagulation

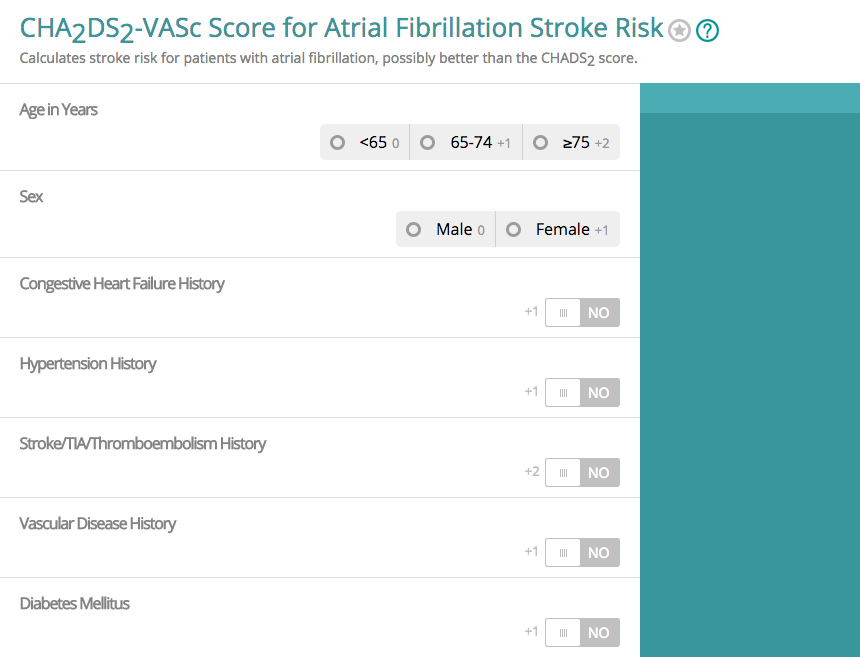

- Numerous risk stratification instruments exist but the CHA2DS2-VASc Score is the most widely accepted tool (Lip 2010)

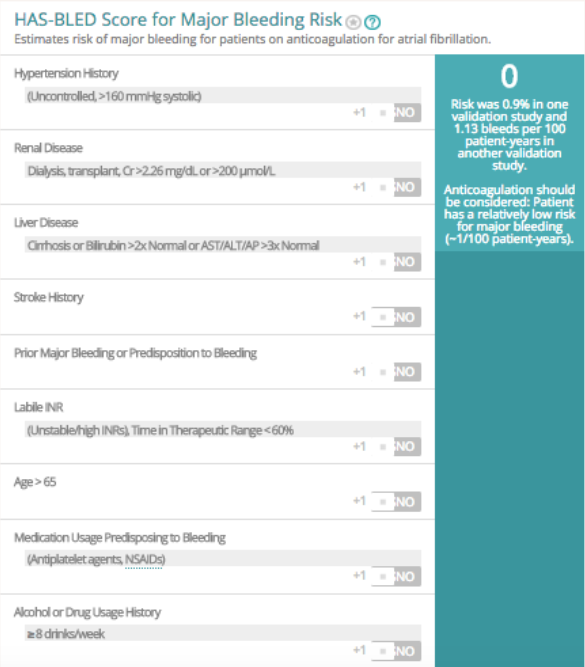

- The risk for developing a systemic embolism should be balanced with the risk for bleeding. The HAS-BLED Score can help with this decision

MDCalc – CHADS-VASC Score

MD Calc – HAS-BLED Score

Disposition:

- AF alone is not an indication for admission to the hospital

- Consider discharge

- Successful rhythm control in patients with low CHA2DS2-VASc Score and follow up (von Besser 2011)

- Successful rate control in patients with low CHA2DS2-VASc Score, minimal symptoms and follow up

- Consider admission

- Patients with high CHA2DS2-VASc Score regardless of successful rate/rhythm control

- Patients requiring multiple doses of IV medications for rate control

- Patients with ischemic symptoms before or after rate/rhythm control

- Patients without lone AF (i.e. other illness leading to AF)

Take Home Points

- Determine whether the atrial fibrillation is chronic or recent-onset and delineate the time of onset if possible.

- Consider that the AF is being caused by another underlying process and treat that cause

- In lone, recent-onset (< 48 hours) AF, either rhythm control or rate control management may be pursued

- Evaluate all recent-onset AF patients for anticoagulation therapy based on their CHA2DS2-VASc Score

Read More

Yealy D, Kosowsky JM: Dysrhythmias, in Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al (eds): Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, ed 8. St. Louis, Mosby, Inc., 2010, (Ch) 79: p 1034-63.

The SGEM: Shock Through the Heart (Ottawa Aggressive Atrial Fibrillation Protocol)

ALiEM: Atrial Fibrillation Rate Control in the ED: Calcium Channel Blockers or Beta Blockers.

ALiEM: Beta Blockers Vs. Calcium Channel Blockers for Atrial Fibrillation Rate Control: Thinking Beyond the ED.

References

Atzema CL, Barrett TW. Managing atrial fibrillation. Ann Emerg Med 2015; 65(5): 532-9. PMID: 25701296

Besser KV, Mills AM. Is Discharge to Home After Emergency Department Cardioversion Safe for the Treatment of Recent Onset Atrial Fibrillation? Ann of EM 2011; 58: 517-20. PMID: 22098994

Chevalier P et al. Amiodarone Versus Placebo and Class Ic Drugs for Cardioversion of Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation: A Meta-Analysis. JACC 2003; 41: 255-62. PMID: 12535819

Coll-Vinent B et al. Management of acute atrial fibrillation in the emergency department: a systematic review of recent studies. Eur J Emerg Med 2013; 20: 151-9. PMID: 23010989

Decker WW, Stead LG. Selecting rate control for recent-onset atrial fibrillation. Ann Emerg Med 2011; 57(1): 32-3. PMID: 21183084

Demircan C et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of intravenous diltiazem and metoprolol in the management of rapid ventricular rate in atrial fibrillation. Emerg Med J 2005;22:411–4. PMID: 15911947

Fromm C et al. Diltiazem vs. metoprolol in the management of atrial fibrillation or flutter with rapid ventricular rate in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2015. PMID: 25913166

Lip GY et al. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest 2010;137(2):263-72. PMID: 19762550.

Michael JA et al. Cardioversion of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 1999; 33(4): 379-88. PMID: 10092714

Scheuermeyer FX et al. Thirty-day Outcomes of Emergency Department Patients Undergoing Electrical Cardioversion for Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter. Acad EM 2010; 17: 408-15. PMID: 20370780

Stiell IG et al. Association of the Ottawa Aggressive Protocol with Rapid Discharge of Emergency Department Patients with Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter. CJEM 2010; 12(3): 181-91. PMID: 20522282

Stiell IG, Birnie D. Managing reent-onset atrial fibrillation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2011; 57(1): 31-2. PMID: 21183083

Van Gelder IC et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. NEJM 2010; 362: 1363-73. PMID: 20231232 (FREE OPEN ACCESS ARTICLE)

Hello. Probably should add pulmonary disease to “causes of AF”. The mnemonic PIRATES might be helpful, but depends on how you feel about mnemonics. Thanks. Love the website and podcast (it’s like free EMRAP!)

Hi, in a new onset AF patient ( heart rate persistent >150 bpm) which is precipitated by infection, do we control the heart rate with antiarrthymic drugs?

Depends on the situation. Often, the tachycardia is necessary to maintain an increased CO to meet the stressed state so treating the rate isn’t the right call (may lead to hypotension and hypoperfusion). I would recommend treating the underlying cause first as you normally would – fluids, antibiotics, source control – and let the heart rate ride for a bit.

AF is a not so uncommon presenting rhythm in submassive/massive PE. I similarly wouldn’t rate control those folks but, rather, treat the underlying issue.

Great article source to read. Thank you for sharing this.