Definition: Complex clinical syndrome resulting from any structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or ejection of blood. It is divided into 2 broad categories as defined by the AHA/ACCF guidelines: (Yancy 2013)

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) or diastolic HF = EF ≥ 50%

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) or systolic HF= EF ≤ 40%

Those with EF 40-49% are in a borderline area and likely represent patients with mild systolic dysfunction.

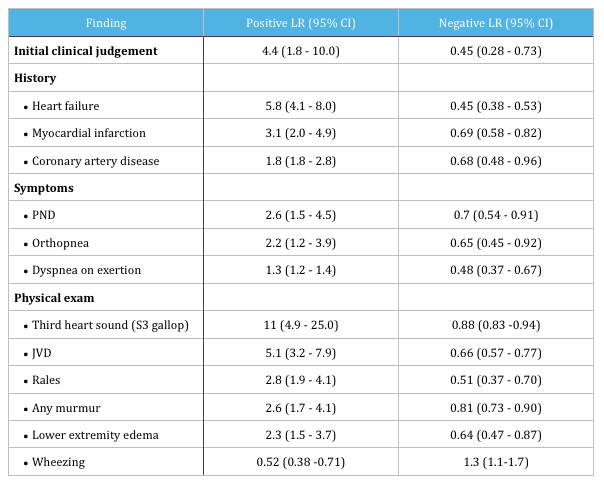

History and Physical Exam: Review of literature assessing diagnostic accuracy of history and physical exam findings in ED patients presenting with dyspnea found that the following increased the likelihood of heart failure (Wang 2005):

Assess for common precipitants of acute decompensated HF (ADHF) These can include:

- Acute myocardial ischemia or infarction

- Arrhythmias – atrial fibrillation

- Pulmonary embolism

- Cardiovascular disorders – valvular disease, myopericarditis, endocarditis, aortic dissection

- Infection

- Anemia

- Uncontrolled HTN

- Medication or diet non-adherence

- Medications – negative inotropic agents, those that promote salt/fluid retention (steroids, NSAIDs)

- Alcohol or illicit drug use

- Endocrine abnormalities – DM, thyroid disorders

Diagnostics:

- EKG

- Look for evidence of ischemia, dysrhythmias (AFib), PE (right heart strain), or other relevant

abnormalities - HF is very unlikely in a patient with a normal EKG

- Look for evidence of ischemia, dysrhythmias (AFib), PE (right heart strain), or other relevant

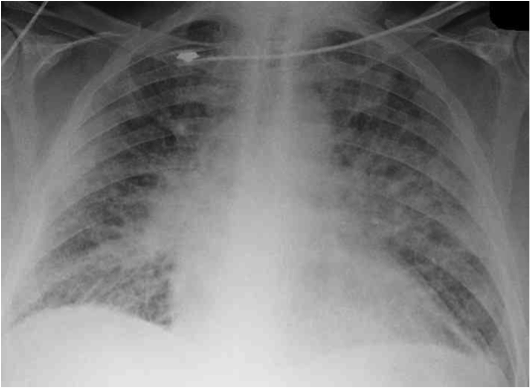

- CXR

- Presence of cardiomegaly, pulmonary venous congestion and interstitial edema are highly suggestive of heart failure (Wang 2005)

- Caution: 15-18% of patients with ADHF will have absence of any findings of congestion on CXR (Horton 2013)

- May be helpful in identifying alternative diagnoses

- Labs including comprehensive metabolic panel including Mg, CBC, troponin, +/- BNP or NT-proBNP

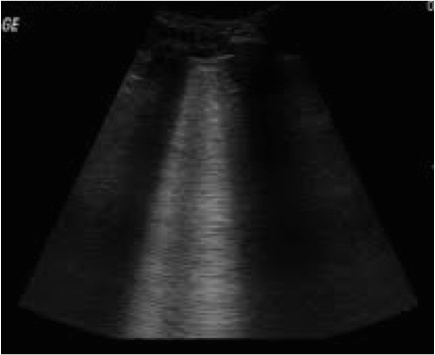

- Obtain prior echocardiography results, if available, and strongly consider performing point of care ultrasound (POCUS) to assess systolic function + the presence or absence of pulmonary edema

Ultrasound Evaluation of Dyspnea (Ultrasound Podcast)

Ultrasound Evaluation of Dyspnea (Ultrasound Podcast)

Utility of BNP or NT-proBNP:

- BNP is a neurohormone secreted mostly by the ventricles in response to volume expansion and pressure overload and can be increased secondary to both cardiac and non-cardiac causes, and decreased in obesity

- Cardiac causes: HF, ACS, LVH, valvular heart disease, pericardial disease, atrial fibrillation, myocarditis

- Non- cardiac causes: advancing age, anemia, renal failure, cirrhosis, pulmonary (PE, OSA, infection, pulmonary HTN, COPD), critical illness (severe burns, sepsis), toxic metabolic insults (chemotherapy, envenomation)

- In patients presenting with acute dyspnea the measurement of BNP or NT-proBNP is may be useful to support clinical judgment for the diagnosis of acutely decompensated HF, especially in the setting of diagnostic uncertainty (Yancy 2013, McMurray 2012, Maisel 2008)

- At this time, there is insufficient evidence to support BNP/NT-proBNP-guided management.

- Read More on BNP: The Case of the Dubious Squire (EM Nerd)

Directed Management:

- ADHF may be due to systolic or diastolic dysfunction with the presence or absence of cardiogenic pulmonary edema

- For unstable patients proceed immediately with emergency stabilization starting with ABCs

- IV, O2, Monitor

- Provide oxygen if O2 < 90% or PaO2 < 60mmHg

- Consider Non-invasive Positive Pressure Ventilation (NIPPV) in setting of respiratory distress, hypercapnia or persistent hypoxia despite supplemental O2

- Cochrane Review showed decreased hospital mortality and decreased need for intubation (Vital 2013)

- NEJM multi-center prospective RCT showed no improvement in short term mortality or need for intubation, but showed more rapid improvement in dyspnea, HR, acidosis, and hypercapnia (Gray 2008)

- Use with caution in hypotensive patients. Positive pressure ventilation can decrease preload and further decrease cardiac output. You need to balance this risk with the need to decrease the patient’s work of breathing.

- Caution: Hyperoxia can cause pulmonary vasoconstriction which can lead to decreased cardiac output. Only provide supplemental oxygen if necessary! (Lewis 2014)

- Loop diuretics

- Administer 1-2 times their TOTAL DAILY DOSE. PO:IV conversion is 2:1.

- Example: If a patient is on 40mg BID of furosemide , their total daily dose = 80mg. Therefore, you should give 40-80mg IV.

- For loop diuretic naive patients, a safe starting dose is furosemide 40mg IV

- Use with caution in patients with aortic stenosis and hypotension

- Administer 1-2 times their TOTAL DAILY DOSE. PO:IV conversion is 2:1.

- Vasodilators: Nitroglycerin

- Nitroglycerin most commonly used and acts primarily as venodilator to decrease left ventricular filling pressures (at higher doses reduces afterload)

- Dose: 5-10mcg/min initial, and increase by 5-10mcg/min q 3-5 minutes (dose range 10-200mcg/min)

- Caution: Avoid in hypotension and in patients with severe mitral or aortic stenosis as they are pre-load dependent. Contra-indicated in patients on PDE-5 inhibitors (i.e, sildenafil)

- Read More: Cardiogenic Shock (Core EM)

Review – Treatment based on presenting BP: (Horton 2013)

- Hypertensive: SBP > 140mmHg:

- Often present more acutely with pulmonary edema and have a rapid response to therapy with lower 60-90 day mortality

- Treatment aimed at preload and afterload reduction with vasodilators as mainstay of therapy

- Caution with over-diuresis as symptoms of pulmonary edema may be due to fluid-shifts from increased hydrostatic pressure rather than volume overload

- Normotensive

- More insidious presentation as result of gradual volume overload

- Treatment should be aimed at diuresis

- Hypotensive

- High inpatient mortality

- Require ICU level care and may require invasive hemodynamic monitoring, mechanical ventilation, IABP, inotropes/vasopressors, diuresis

Take home points:

- Don’t forget to assess for and treat precipitants of ADHF, including potentially dangerous causes such as myocardial ischemia, dysrhythmias, PE, or infection.

- POCUS is an invaluable tool both for the diagnosis and management of ADHF

- BNP or NT-proBNP may be useful to exclude ADHF in the ED patient with undifferentiated dyspnea, however at this time there is insufficient evidence to support its use in guiding management

- Treatment of ADHF should be tailored to the patient’s clinical presentation often includes a combination of diuretics and vasodilators, +/- NIPPV

References:

- Yancy CW et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128(16):e240-e327. PMID: 23741058

- McMurray JJ et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(8):803-869. PMID: 22828712

- Wang CS et al. Does This Dyspneic Patient in the Emergency Department Have Congestive Heart Failure?. JAMA. 2005;294(15):1944-1956. PMID: 16234501

- Lewis T. Current guidelines for the evaluation and management of heart failure. EM Practice Guidelines Update. January/February 2014; 6 (1):1-12

- Maisel A et al. State of the art: Using natriuretic peptide levels in clinical practice. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008 Sep;10(9):824-39. PMID: 18760965

- Horton CF, Collins SP. The role of the emergency department in the patient with acute heart failure. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2013 Jun;15(6):365. PMID: 23605467

- Vital FM et al. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (CPAP or bilevel NPPV) for cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 May 31;5:CD005351. PMID: 23728654

- Gray A et al. Noninvasive ventilation in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jul 10;359(2):142-51. PMID:18614781