Drugs Affecting the Cardiac Cycle

Background

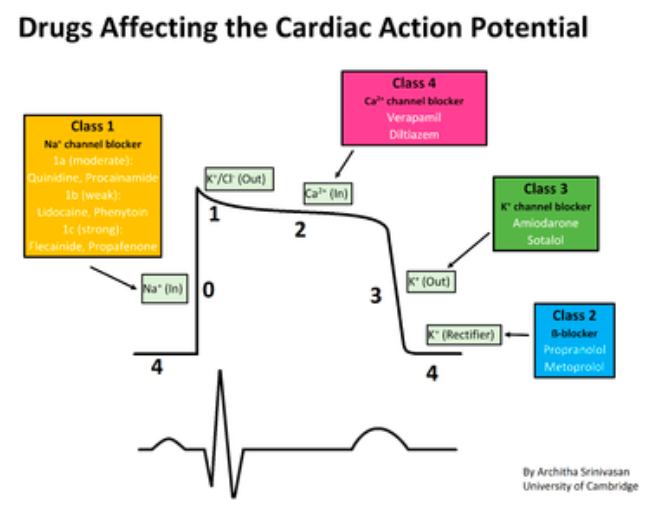

Amiodarone is a class III antidysrhythmic first released for human use in 1962. As with other drugs in this class, amiodarone acts by blocking potassium channels thus prolonging the action potential. This, in turn, leads to a lengthening of depolarization of the atria and ventricles. The drug spread rapidly through US hospitals as it was touted as “always works, and no side effects,” by it’s pharmaceutical manufacturer (Bruen 2016).

Of course, nothing comes free and soon after the drug became widely used, a multitude of adverse effects became apparent. These included minor issues – sun sensitivity and corneal deposits – to major ones – thyroid dysfunction (hypo- and hyperthyroidism), pulmonary toxicity and liver damage. Additionally, the medication’s mechanism of action wasn’t clean and simple – amiodarone is no known to have sodium-channel blocking (Class I), beta-blocking (Class II) and calcium-channel blocking (Class IV) effects.

Despite the multitude of issues, the drug continued to be used extensively because of it’s purported benefits. The drug was most commonly applied in the Emergency Department (ED) for conversion of atrial fibrillation, conversion of stable ventricular tachycardia and in refractory VF/VT cardiac arrest.

This post dives into the three most common places amiodarone is employed in the ED: cardioverion of atrial fibrillation, cardioversion of VT and in refractory VF/VT cardiac arrest and demonstrates that superior evidence points to better options for management.

Amiodarone for Atrial Fibrillation Cardioversion

Termination of recent-onset atrial fibrillation (AF) or flutter (AFl) can be accomplished either by chemical or electrical cardioversion in the ED. Chemical cardioversion is typically pursued with amiodarone. Meta-analyses have demonstrated an increased conversion rate for amiodarone versus placebo (Chevalier 2003, Letelier 2003). However, the effect was delayed. Letelier looked at conversion within 4 weeks of administration of the drug; a time table that is not useful in terms of ED management (Letelier 2003). Short-term outcomes are subpar as well with no increased conversion in comparison to placebo at 1 or 2 hours after administration (Chevalier 2003). It was only at the 6-8 hour mark when amiodarone began to show superiority to placebo. Similarly, amiodarone was worse in terminating AF when compared to class Ic drugs including flecainide and propafenone at up to 8 hours after administration (Chevalier 2003). It was only at 24 hours that amiodarone reached a similar conversion rate to these drugs. This timetable for conversion is unacceptable in the ED.

Procainamide (Class Ia antidysrhythmic) has shown similar conversion rates to amiodarone but, has the benefit of a more rapid effect. Median time to conversion has been shown to be around 55 minutes with procainamide (Stiell 2007). Since the drug needs to be given as an infusion over 45-60 minutes, this means that in many patients, conversion will occur during the infusion. I generally expect to have a result of the infusion during the infusion up to 15-30 minutes post-infusion. If the patient hasn’t terminated at this point, the procainamide attempt has failed and we should move on to alternate options. Flecainide and propafenone are frequently unavailable for use.

For the patient with a wide-complex AF (i.e. AF with Wollf-Parkinson-White) amiodarone, though recommended by the America Heart Association (AHA for over a decade as 1st line chemical therapy, should not be given. Due to it’s effects on sodium channels, calcium channels and beta-blocking properties, the drug may lead to adverse outcomes including acceleration of rate and ventricular fibrillation (Tijunelis 2005). Procainamide has a more established track record in these patients and should be considered first line if chemical conversion is pursued.

Electrical cardioversion (with procedural sedation), unlike either medication, has a considerably higher success rate (> 90%) and works immediately (Stiell 2010). The Ottawa aggressive protocol recommends starting with procainamide and following with electricity if the drug fails but many providers will start with electricity thus obviating the need for any medication. Electrical cardioversion is similarly safe and efficacious in AF with WPW.

Amiodarone for Ventricular Tachycardia Cardioversion

Similar to atrial fibrillation, patients with hemodynamically stable ventricular tachycardia (VT) can be managed with either chemical or electrical cardioversion. Amiodarone is frequently used for this indication and has been recommended by the AHA for this indication since 2000. Prior to the addition of amiodarone for hemodynamically stable VT, lidocaine was the drug of choice. To date, there are no high-quality studies directly demonstrating the superiority of amiodarone to lidocaine in the emergency management of VT. Two small ED retrospective studies demonstrate the ineffectiveness of bolus dose amiodarone for termination of VT (Marill 2006, Tomlinson 2008). What about our friend procainamide?

The PROCAMIO study compared amiodarone to procainamide in a randomized open-label trial with a primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac events and a secondary endpoint of efficacy (Ortiz 2016). Procainamide won on both endpoints. Procainamide (10 mg/kg over 20 min) had a lower frequency of adverse events (9% vs. 41% OR 0.1 NNH = 3) as well as a superior termination rate (67% vs. 38% OR 3.3 NNT = 3.3) in comparison to amiodarone (5 mg/kg over 20 min). The rate of adverse events in the group of patients with structural heart disease was lower in the procainamide group as well. Though it’s only one study, it represents the best quality of evidence we have to date.

Once again, electrical cardioversion is the superior approach for tachydysrhythmia termination. In the PROCAMIO study, only 33/62 patients converted when given either procainamide or amiodarone – almost half of the patients needed to proceed to electricity for termination. Though some patients will remain in hemodynamically stable VT for prolonged periods of time, the risk of decompensation to unstable VT or VF is always present. All of this underscores the need to always have defibrillator pads applied to the patient and have a plan for failed chemical cardioversion in place. Based on the overall low rate of chemical cardioversion, electing to go directly to electricity is a reasonable and possibly superior approach.

Amiodarone in Refractory VF/VT Cardiac Arrest

Amiodarone is a staple drug in refractory cardiac arrest where it replaced the use of lidocaine for the same indication. However, the available evidence has never supported it’s use in terms of meaningful outcomes. Amiodarone was embraced and brought into the ACLS algorithm on the result of two studies demonstrating improved rates of ROSC and admission to hospital (Kudenchuk 1999, Dorian 2002). Neither of these studies demonstrated an improvement in neurologically intact survival which is the more important outcome. Two subsequent meta-analysies again revealed an improvement only in ROSC but not in discharge home in good neurologic condition (Laina 2016, Sanfilippo 2016). The topic was revisited in 2016 in ALPs trial looking at amiodarone versus lidocaine versus placebo in patients with refractory VF or VT arrest. In this high-quality RDCT, the researchers found no increase in ROSC or neurologic outcomes in comparison to placebo (Kudenchuk 2016). This study did show a possible benefit in early administration of amiodarone but further studies would be necessary to elucidate this hypothesis.

Regardless of potential benefits in subgroups, the whole of the available evidence demonstrates a possibility for increased ROSC rates but no improvement in neurologic outcomes. Instead of considering the use of amiodarone, we should instead focus on interventions that are known to improve outcomes – good compressions and defibrillation when indicated.

Bottom Line

There is a danger in summarizing a complicated topic with a one liner but, in regards to amiodarone, the best available evidence does not show any clear benefit for any of the major indications for ED use. However, the drug does have proven harms (i.e. hypo/hyperthyroidism, pulmonary toxicity, acute liver disorders). Given that we have better options for stable AF and VT cardioversion and that we have more important interventions to focus on in cardiac arrest, amiodarone should not be routinely used for any of these indications.

Read More

Amiodarone in Atrial Fibrillation

Core EM: Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation

Core EM: Episode 98.0 – Cardioversion in Recent Onset AF

Core EM: Ottawa Aggressive Atrial Fibrillation Protocol

Amiodarone in VT

Core EM: Procainamide vs Amiodarone in Stable Wide QRS Tachydysrhythmias (PROCAMIO)

EM Nerd: The Case of the Dysrhythmic Heart

REBEL Cast: PROCAMIO Trial

Amiodarone in Cardiac Arrest

Core EM: Amiodarone, Lidocaine or Placebo in OHCA

References

Bruen C. Spontaneous Circulation: Rebellions of the Heart: The End of Amiodarone. Emery Med News 2016; 38(11): 6-8. Link

Letelier LM et al. Effectiveness of amiodarone for conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163: 777-85. PMID: 12695268

Chevalier P et al. Amiodarone Versus Placebo and Class Ic Drugs for Cardioversion of Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation: A Meta-Analysis. JACC 2003; 41: 255-62. PMID: 12535819

Stiell IG et al. Emergency department use of intravenous procainamide for patients with acute atrial fibrillation or flutter. Acad Emerg Med 2007; 14: 1158-64. PMID: 18045891

Stiell IG et al. Association of the Ottawa Aggressive Protocol with Rapid Discharge of Emergency Department Patients with Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter. CJEM 2010; 12(3): 181-91. PMID: 20522282

Stiell IG et al. Outcomes for Emergency Department Patients with Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation and Flutter Treated in Canadian Hospitals. Ann Emerg Med 2017. PMID: 28110987

Tijunelis M, Herbert M. Myth: Intravenous amiodarone is safe in patients with atrial fibrillation and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in the emergency department. Can J Emerg Med 2005; 7(4): 262-5. PMID: 17355684

Tomlinson DR et al. Intravenous amiodarone for the pharmacological termination of haemodynamically-tolerated sustained ventricular tachycardia: is bolus dose amiodarone an appropriate first-line treatment? Emerg Med J 2008; 25: 15-18. PMID: 18156531

Marill KA et al. Amiodarone is poorly effective for the acute termination of ventricular tachycardia. Ann Emerg Med 2006; 47: 217-24. PMID: 16492484

Ortiz M et al. Randomized Comparison of Intravenous Procainamide vs. Intravenous Amiodarone for the Acute Treatment of Tolerated Wide QRS Tachycardia: the PROCAMIO Study. Eur Heart J 2016. PMID: 27354046

Dorian P et al. Amiodarone as compared with lidocaine for shock-resistant ventricular fibrillation. NEJM 2002; 346(12): 884-90. PMID: 11907287

Kudenchuk PJ et al. Amiodarone for reuscitation after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation. NEJM 1999; 341(12): 871-8. PMID: 10485418

Laina A et al. Amiodarone and cardiac arrest: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Card 2016; 221: 780-8. PMID: 27434349

Sanfilipo F et al. Amiodarone or lidocaine for cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2016; 107: 31-7. PMID: 27496262

Kudenchuk PJ et al. Amiodarone, Lidocaine, or Placebo in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. NEJM 2016. PMID: 27043165

Joglar JA, Page RL. Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest – Are Drugs Ever the Answer? NEJM 2016. PMID: 27042874

Is there evidence for any of these complications occurring with any significant frequency in SHORT TERM use? I have never heard of, say, pulmonary fibrosis occurring after a bolus and 24-hour drip of amiodarone.

From what I’ve read, this can occur after even a single dose. Clearly, uncommon but, there is risk.

Any references? I had always understood it to be a pretty safe drug (that is, just the predictable side effects, e.g. negative inotropy and interval prolongation) when used acutely.

As always….you can’t rely only on “studies” and the new buzz phrase “evidence based practice”. There is such a thing as relying on what you have seen work time and time again! From your experience as a health care professional! I for instance have always been a fan of lidocaine. It simply works from what I’ve seen especially in patients who are not necessarily in v-tach but that are having a ton of ectopy and are at risk for going into v-tach. It just calms that heart muscle right down….I’ve seen it work over and over again, then all of a sudden no no no lidocaine is not drug of choice anymore and the new drug of choice is one that takes much more time to see the benefit. Drug companies are behind all of “studies” and “information”. They are trying to make a buck! Why would we trust them. Use your brain…your skills…and trust your experience! That’s what I say!