Show Notes

Background:

- The most common infection seen in pediatrics and the most common reason these kids receive antibiotics

- The release of the PCV (pneumococcal conjugate vaccine), or Prevnar vaccine, has made a big difference since its release in 2000 (Marom 2014)

- This, along with more stringent criteria for what we are calling AOM, has led to a significant decrease in the number of cases seen since then

- 29% reduction in AOM caused by all pneumococcal serotypes among children who received PCV7 before 24 months of age

- The peak incidence is between 6 and 18 months of age

- Risk factors: winter season, genetic predisposition, day care, low socioeconomic status, males, reduced duration of or no breast feeding, and exposure to tobacco smoke.

- The predominant organisms: Streptococcus pneumoniae, non-typable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi), and Moraxella catarrhalis.

- Prevalence rates of infections due to Streptococcus pneumoniae are declining due to widespread use of the Prevnar vaccine while the proportion of Moraxella and NTHi infection increases with NTHi now the most common causative bacterium

- Strep pneumo is associated with more severe illness, like worse fevers, otalgia and also increased incidence of complications like mastoiditis.

Diagnosis

- The diagnosis of acute otitis media is a clinical one without a gold standard in the ED (tympanocentesis)

- Ear pain (+LR 3.0-7.3), or in the preverbal child, ear-tugging or rubbing is going to be the most common symptom but far from universally present in children. Parents may also report fevers, excessive crying, decreased activity, and difficulty sleeping.

- Challenging especially in the younger patient, whose symptoms may be non-specific and exam is difficult

- Important to keep in mind that otitis media with effusion, which does not require antibiotics, can masquerade as AOM

AAP: Diagnosis of Acute Otitis Media (2013)*

- In 2013, the AAP came out with a paper to help guide the diagnosis of AOM

- Moderate-Severe bulging of the tympanic membrane or new-onset otorrhea not due to acute otitis externa (grade B)

- The presence of bulging is a specific sign and will help us distinguish between AOM and OME, the latter has opacification of the tympanic membrane or air-fluid level without bulging (Shaikh 2012, with algorithm)

- Bulging of the TM is the most important feature and one systematic review found that its presence had an adjusted LR of 51 (Rothman 2003)

- Classic triad is bulging along with impaired mobility and redness or cloudiness of TM

- Mild bulging of the tympanic membrane AND (grade C)

- Recent onset (48hrs)

Ear pain (verbal child)

Holding, tugging, rubbing of the ear (non-verbal child)

OR

- Intense erythema of the tympanic membrane

* The diagnosis should not be made in the absence of a middle ear effusion (grade B)

Treatment Options

- A strategy of “watchful waiting” in which children with acute otitis media are not immediately treated with antibiotic therapy, has been endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

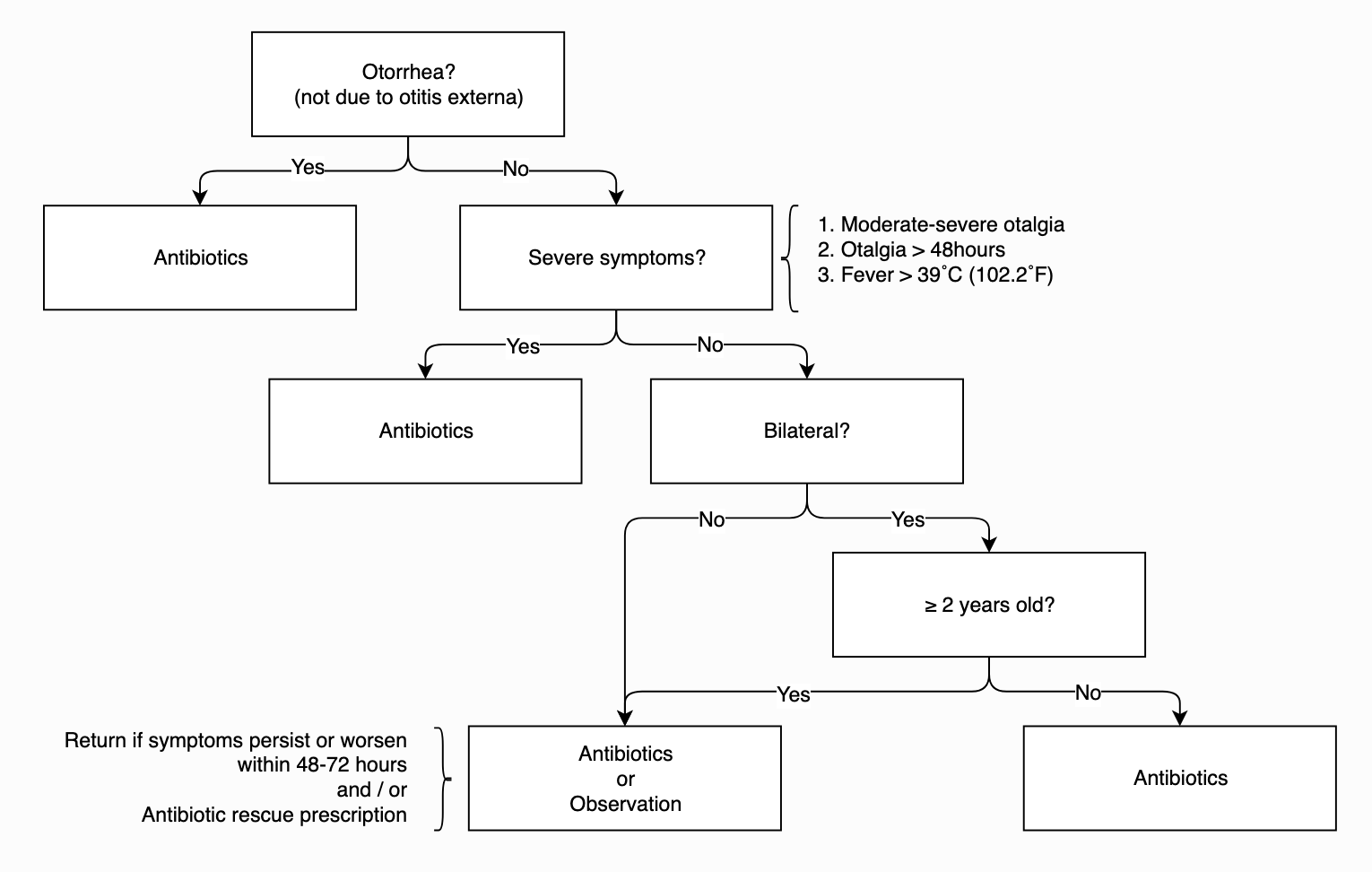

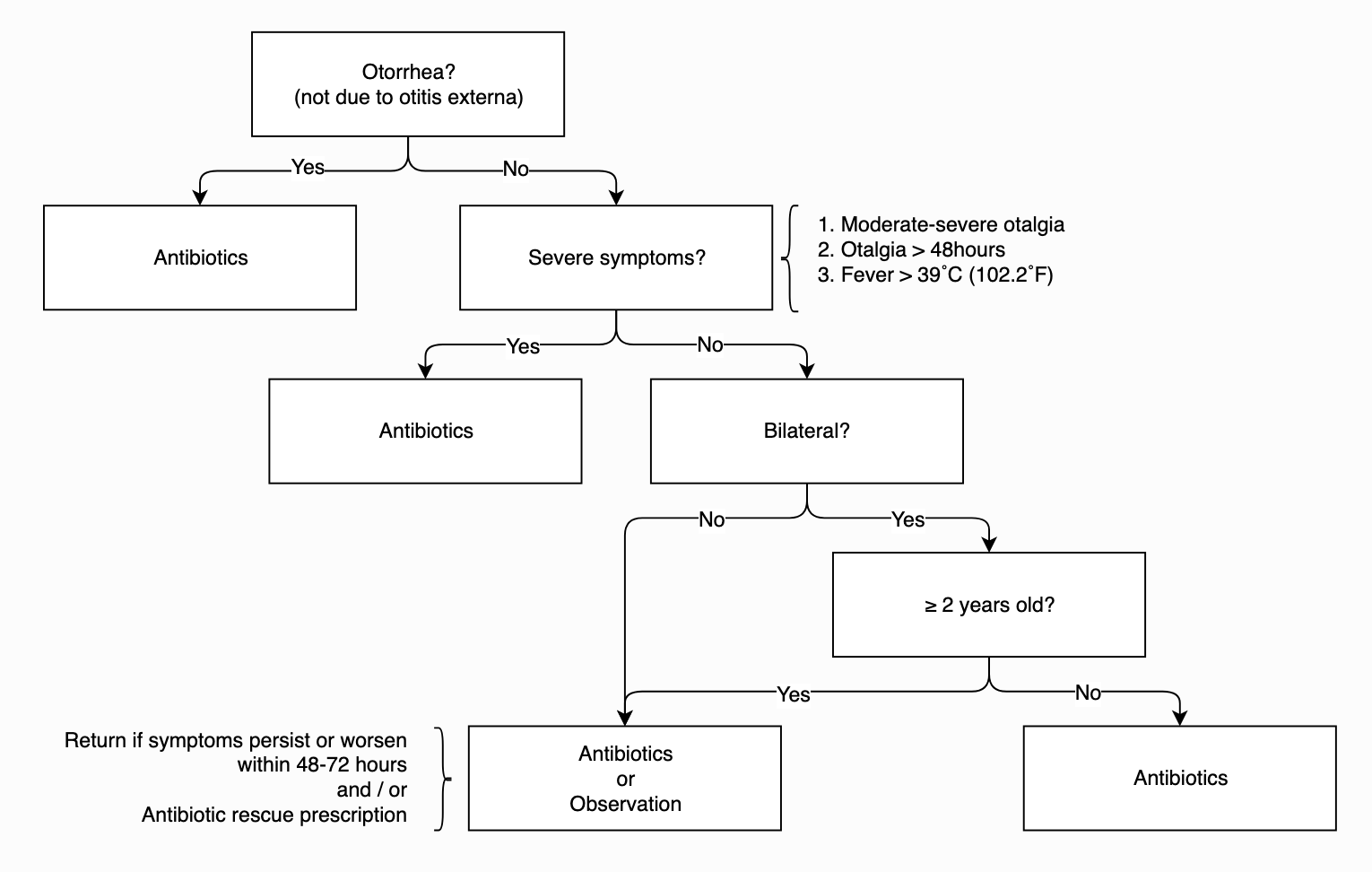

- Who gets antibiotics?

- Depends on age, temperature, duration of otalgia, laterality / otorrhea, and access to follow up

- Get’s antibiotics:

- <6 months: Treat

- 6 months to 2 years: Treat

- Exception, AAP permits initial observation: unilateral AOM with mild symptoms (mild ear pain, <48h, T <102.2)

- But know that there is a high rate of treatment failure (Hoberman 2013)

- >2: Treat

- Unless they have mild symptoms and it’s unilateral, you can observe for 48-72 hours

- Why do we give antibiotics?

- Demonstrated reduction in pain, TM perforations, contralateral episodes of AOM

- They are no walk in the park, with increased adverse events (vomiting, diarrhea, rash)

- Two well-designed clinical trials (2011) randomized approximately 600 children meeting strict diagnostic criteria for acute otitis media to receive Augmentin or placebo. These studies demonstrated a significant reduction in symptom burden and clinical failures in those who received antibiotics.

- The authors conclude that those patients with a clear diagnosis of acute otitis media would benefit from antibiotic therapy

AAP AOM Treatment Algorithm

Antibiotic Selection

- High-dose amoxicillin in most (for now)

- Amoxicillin should not be used if the patient has received Amoxicillin in the past 30 days, has concomitant purulent conjunctivitis (likely H flu) or is allergic to penicillin.

- beta lactamase resistant antibiotic should be used.

- Amoxicillin clavulanate or 2nd or 3rd generation cephalosporins (including intramuscular ceftriaxone).

- Patients with a history of type 1 hypersensitivity reactions to penicillin should be treated macrolides.

- Studies on duration of therapy have shown better results with 10-day duration in children younger than 2 years and suggest improved efficacy in those 2-5 years.

- For patients older than 5 years, shorter course therapy (5-7 days) can be utilized.

Pain Control

- Motrin and APAP may have benefit with otalgia reduction

Other

- Decongestants and antihistamines have been shown to not benefit patients in terms of duration of symptoms or complication rate. Not surprisingly, these agents increase the side-effects experienced by patients.

Follow up

- If you chose to observe, let the parents know to return to ED or f/u with their provider in 48-72 hours if they symptoms do not improve. Providing a prescription to parents with clear instructions on when to fill it is also an acceptable option. Strict return precautions should be given if patient develops meningismus or facial nerve palsy.

- If antibiotics were initiated, and there isn’t improvement in 2-3 days, the diagnosis of AOM should be revisited and, if still suspected, we have to consider that the causative bug is resistant to the prescribed antibiotic.

- These patients should RTED or f/u with their pediatrician for escalation of care

- Amoxicillin → Augmentin

- Augmentin → Ceftriaxone IM

- Macrolide → no clear antimicrobial agent, consult pediatric ENT

- If antibiotics are initiated with resolution of symptoms, the patient should f/u in 2-3 months to ensure resolution of the middle ear effusion and ensure that there is no associated conductive hearing loss

References:

Coker TR, Chan LS, Newberry SJ, Limbos MA, Suttorp MJ, Shekelle PG, et al. Diagnosis, microbial epidemiology, and antibiotic treatment of acute otitis media in children: a systematic review. JAMA. 2010;304(19):2161-9.

Hoberman A, Ruohola A, Shaikh N, Tahtinen PA, Paradise JL. Acute otitis media in children younger than 2 years. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(12):1171-2.

Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, Ganiats TG, Hoberman A, Jackson MA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e964-99.

Marom T, Tan A, Wilkinson GS, Pierson KS, Freeman JL, Chonmaitree T. Trends in otitis media-related health care use in the United States, 2001-2011. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(1):68-75.

Rothman R, Owens T, Simel DL. Does this child have acute otitis media? JAMA. 2003;290(12):1633-40.

Shaikh N, Hoberman A, Rockette HE, Kurs-Lasky M. Development of an algorithm for the diagnosis of otitis media. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(3):214-8.

Venekamp RP, Sanders S, Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB, Rovers MM. Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(1):CD000219.

See our core article on the topic by Dr. Deborah Levine and Dr. Michael Mojica here

A special thanks to our editors:

Michael A. Mojica, MD

Director, Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellowship

Bellevue Hospital Center

Christie M. Gutierrez, MD

Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellow

Columbia University Medical Center

Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital

New York Presbyterian