Background

This review is cross-posted on REBEL EM.

Over the last three years, we have seen the rise of neurointerventional therapies for patients with ischemic strokes due to large vessel occlusions (LVOs). This group of strokes typically includes patients with occlusion of the distal intracranial carotid artery, middle cerebral artery or anterior cerebral artery. Rapid identification of these patients both in the prehospital setting as well as in the emergency department (ED) may be beneficial as it can lead to mobilization of necessary resources and ordering of proper investigations (CT perfusion, MRI/MRA). While there are a number of clinical scoring systems in place to identify patients with LVO, none are ideal. The authors investigate the utility of the vision, aphasia, neglect (VAN) assessment for this purpose.

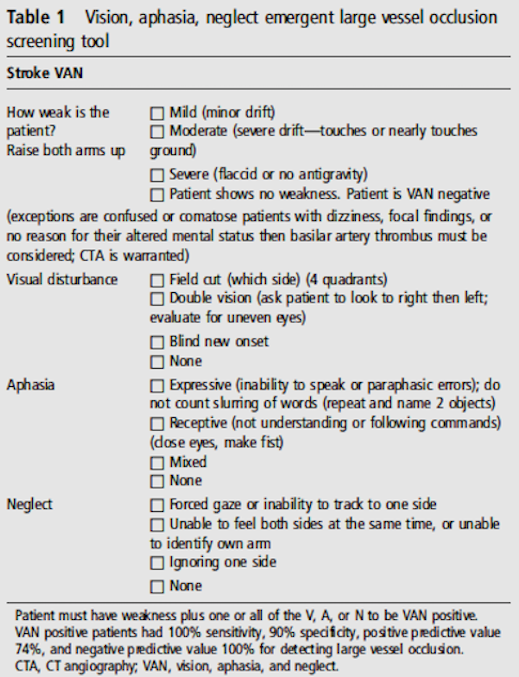

The VAN assessment (see table below) begins with a simple assessment of upper extremity weakness. If the patient exhibits weakness (minimum is any drift) they then proceed to vision, aphasia and neglect testing. If either vision, aphasia or neglect assessment is abnormal, the patient should be suspected of having a LVO. If there is no weakness, the patient is deemed to not have an LVO and the vision, aphasia and neglect pieces of the assessment are not carried out.

The VAN Assessment

Definition:

Emergent Large Vessel Occlusion (ELVO) = Thromboembolic occlusion of an M1 segment of the middle cerebral artery, internal carotid artery, basilar artery, or M2 segment for which endovascular therapy would be considered

Note: This study uses the term ELVO but in the general literature, LVO is the term used and, the term we will use during this post.

Clinical Question

How does the VAN assessment perform in comparison to an NIHSS score > 6 for the identification of LVO?

Population

Any patient for whom a stroke code was activated during this pilot study.

Outcomes

(Primary): Test performance characteristics of the VAN assessment in comparison to an NIHSS > 6 for identification of LVO

Design

Pilot prospective, cohort study performed in a single hospital

Excluded

No exclusions specified

Primary Results

- 62 consecutive acute stroke code activations included

- All patients had a VAN and NIHSS score calculated

Critical Findings

- VAN (+) patients = 19 (14 with LVO)

- 5 patients VAN positive without LVO (False Positive): multiple distal MCA embolic strokes, hypoxia with global weakness, seizure secondary to old AVM resection, conversion reaction, and complex migraine

- NIHSS > 6 patients = 24 (14 with LVO)

- All patients who were eligible for neurointerventional therapy were VAN (+) and NIHSS > 6 (i.e. neither clinical test missed an eligible patient)

- 30% of stroke codes had no weakness and were cleared by the VAN assessment within 15 seconds of assessment

- The average time from symptom onset to stroke code activation and VAN assessment was 2hrs (Range: 40min – 5hr 25min)

|

LVO |

No LVO |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

LR (+) |

LR (-) |

||

|

VAN (+) |

14 |

5 |

100% |

90% |

10 |

0 |

|

|

VAN (-) |

0 |

43 |

|||||

|

NIHSS > 6 (+) |

14 |

10 |

100% |

78% |

4.55 |

0 |

|

|

NIHSS > 6 (-) |

0 |

38 |

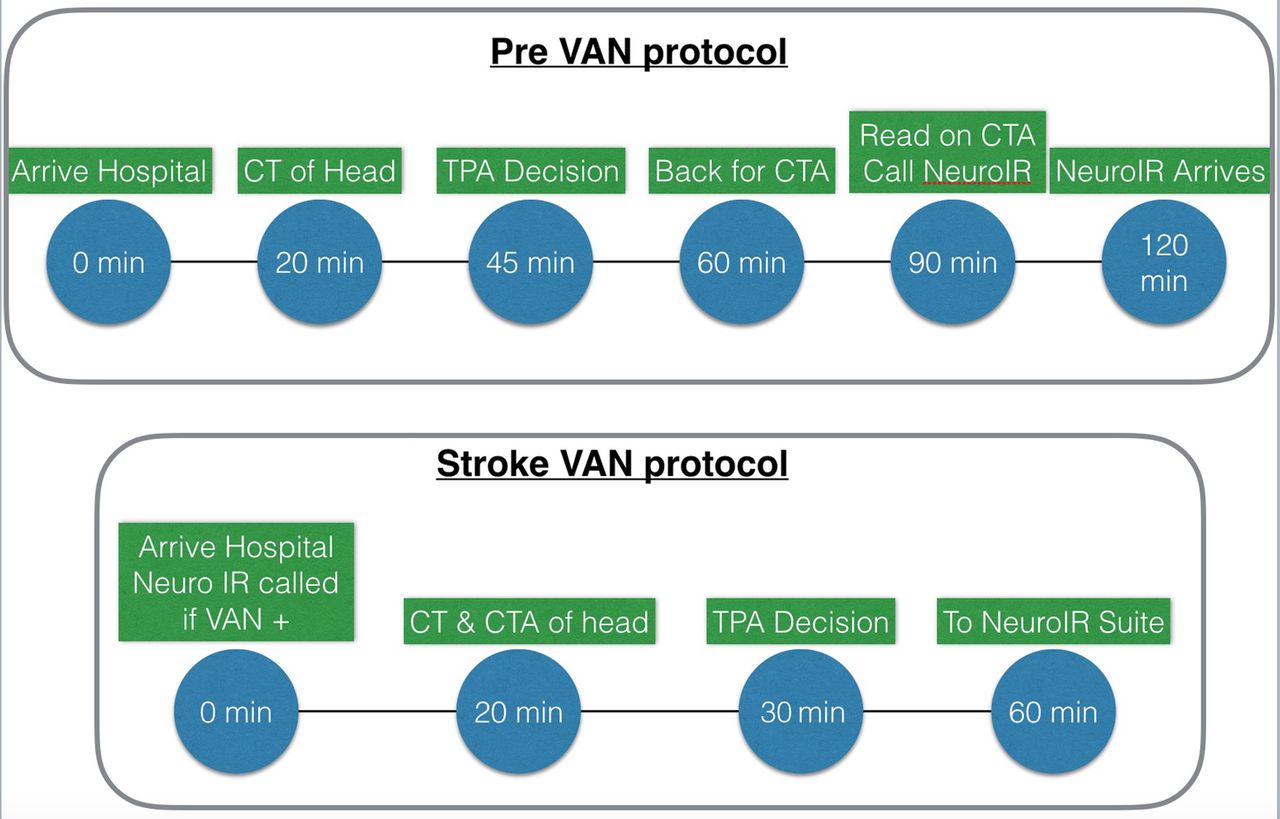

Pre-VAN Protocol vs. Post VAN Protocol (Teleb 2017)

Strengths

- Asks a clinically important question based on current stroke care

- Attempts to develop a simple system for identification of LVO that can be used at triage

- Did not employ specially trained research assistants to perform the assessment but rather trained current staff to perform

- Interobserver reliability of VAN between nurses and stroke physicians was 100%

- Prospectively piloted and compared to current standard care (i.e. NIHSS)

Limitations

- Single center study

- Clear patient inclusion criteria were not specified in this study. The authors did not specify what presentations led to a stroke code activation or how many patients who presented were not included though they do state that the patients were enrolled consecutively

- All ED nurses (previously NIHSS certified) underwent a 2-hour training on VAN. Institution of this system at other hospitals would require the same investment of resources. Additionally, it’s unclear what level of retention of the training would be seen over time

- Small, pilot study and due to emphasis on the study and training involved, there was likely a Hawthorne Effect seen

- The authors stress that with the VAN assessment nothing needs to be calculated (as with the NIHSS score) but each piece of the VAN assessment has multiple possible outcomes that need to be evaluated

- Study does not state how long it took for an NIHSS score to be calculated so unclear how much time this may have saved

- Requires prospective validation in a larger population prior to implementation

- Study may have underestimated number of clots lysed before vessel imaging for VAN due to vessel imaging being conducted after administration of systemic tPA

Other Issues

- Authors state that although VAN was used in the ED it may be superior to many prehospital triage tools used to assess for ELVO

- Sensitivity of other prehospital scores:

- VAN = 100% (Not assessed prehospital)

- RACE (Rapid Arterial oCclusion Evaluation) = 85%

- LEGS (Legs, Eyes, Gaze, Speech) = 69%

- LAMS (Los Angeles Motor Scale) = 81%

- 3I-SS (3 Item Stroke Scale) = 67%

- CPSSS (Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Severity Scale) = 83%

Author's Conclusions

“The VAN screening tool accurately identified ELVO patients and outperformed a NIHSS ≥6 severity threshold and may best allow clinical teams to expedite care and mobilize resources for ELVO patients. A larger study to both validate this screening tool and compare with others is warranted.”

Our Conclusions

We agree with the authors conclusions. In this small pilot study, VAN assessment performed well in identifying patients with LVO but a larger study is necessary to further assess it’s utility before wide incorporation into practice.

Potential Impact To Current Practice

This study should not impact current practice at this point as far as determining which patients should be considered for endovascular therapy for ischemic CVA.

One potential place that can be beneficial is in simply applying the motor weakness screen to rule out patients for consideration. Motor weakness can be rapidly assessed and it’s absence is inconsistent with a LVO. Some stroke systems recommend stroke team activation for patients with stroke-like symptoms up to 24 hours out of onset due to the possibility that patients may be eligible for interventional care. This is an enormous utilization of resources and instead, we should attempt only to activate for patients with evidence of LVO. Adoption of a simple motor weakness screen may allow for a reduction in stroke activation by elimination patients from consideration of LVO.

Bottom Line

The VAN assessment is a novel approach to rapid identification of patients with ischemic stroke from potential LVO who may be eligible for endovascular therapy. We await further research prior to making any further recommendations.