Background

The simplified PE Severity Index (sPESI) is one of several validated prognostic tools for acute pulmonary embolism (PE). The European Society of Cardiology recommended the use of the sPESI to risk-stratify patients with acute PE into low risk (sPESI=0) and non-low risk (sPESI≥1) in order to guide treatment and disposition (Konstantinides 2014). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have found that outpatient management of low-risk PE patients with standard therapy is safe, effective, and cost-effective (Aujesky 2011, Zondag 2013, Kahler 2015).

Standard practice in the United States for treatment of acute PE over the last decade has been a parenteral agent (e.g. enoxaparin, fondaparinux) overlapping with a vitamin K antagonist (VKA) (e.g. warfarin). However, a paradigm shift has been brewing over recent years. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have demonstrated efficacy as initial and long-term treatment of PE compared to standard therapy in various trials (EINSTEIN-PE 2012, RE-COVER 2014, AMPLIFY 2013, Hosukai-VTE 2013). The EINSTEIN-PE study found that rivaroxaban was noninferior to enoxaparin/VKA for the treatment of recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) without increased risk of bleeding. Rivaroxaban and other DOACs are approved for treatment of VTE in the European Union, but use in the United States of DOACs for ED treatment of PE is more limited.

Clinical Question

What is the safety and efficacy of rivaroxaban in patients with a range of sPESI scores in comparison to standard treatment with enoxaparin/VKA?

Population

Patients with symptomatic PE with or without DVT. sPESI scores were assigned to 4,831 out of 4,832 patients from the original EINSTEIN-PE study. HESTIA score was not used as it includes social factors that were not available from the data. sPESI and HESTIA scores are decision instruments that help clinicians predict short-term adverse outcomes in patients with PE.

Intervention

Rivaroxaban 15 mg BID x 3 weeks followed by 20 mg once a day

Control

Enoxaparin/VKA (INR 2.0-3.0)

Outcomes

Adverse outcomes were recurrent VTE, fatal PE, major bleeding, and all-cause mortality at 7, 14, 30, and 90 days. Major bleeding was defined as hemoglobin drop of 2.0g/dL, need for transfusion ≥2 units pRBCs, intracranial bleeding, or retroperitoneal bleeding.

Design

Post hoc analysis of the original data gathered from the original EINSTEIN-PE study – an open-label, randomized, phase III study comparing rivaroxaban with enoxaparin/VKA for a 3, 6, or 12 months as treatment for acute symptomatic PE.

Primary Results

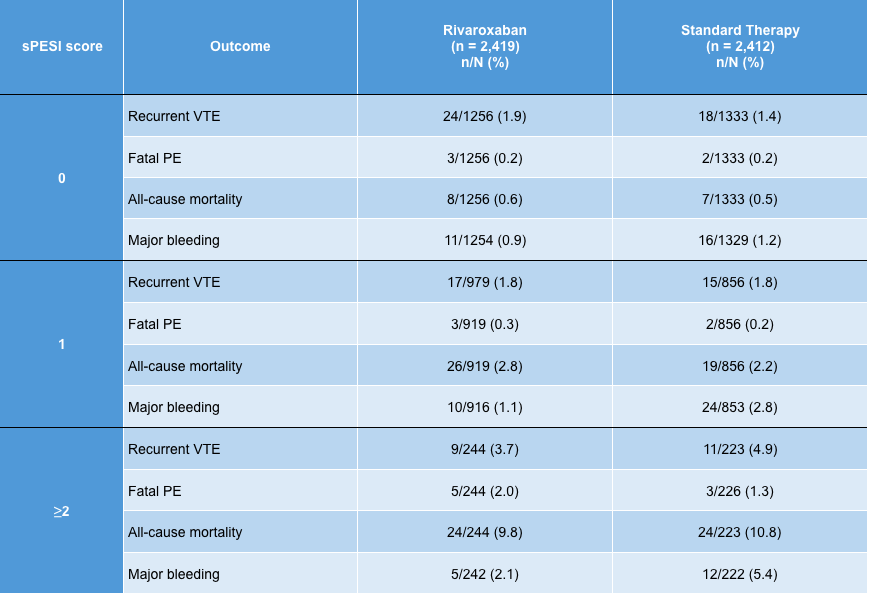

- Distribution of sPESI scores:

- sPESI=0 2,589 (53.6%)

- sPESI=1 1,775 (36.7%)

- sPESI≥2 (2 or 3) 467 (9.7%)

- The patient composition of the original EINSTEIN-PE study was similar to available registry data on overall composition of patients presenting to EDs in the U.S.

- A higher sPESI score was associated with an increase of all the major adverse outcomes at all time points regardless of treatment group

Critical Results

Strengths

- This post hoc analysis effectively applies the simple sPESI score to an existing dataset yielding straightforward raw associations

- The dataset appears to be consistent with overall composition of U.S. ED patients, further supporting the validity of the EINSTEIN-PE study

- The original data came from a large (> 4800 patients), randomized trial looking at an important clinical outcome (recurrent VTE, major bleeding)

Limitations

- Data are unadjusted, with small patient numbers per subgroup and low event rates. This raises questions about both statistical and clinical significance.

- Post hoc analyses are at risk for drawing unreliable associations in the data; there is a well-known increased risk of false positives by finding associations that are not there and/or perpetuating biases from the existing data.

- The original data was derived from a study that was open-label introducing issues of bias associated with non-blinding

Author's Conclusions

“The findings support using risk stratification with the simplified PESI score to identify low risk

patients with PE.”

Our Conclusions

In this post hoc analysis, a higher sPESI correlated with a higher rate of adverse events, thereby corroborating previous validation studies. Furthermore, when stratified by sPESI, the safety and efficacy outcomes for patients treated with rivaroxaban versus standard therapy were similar.

Potential Impact To Current Practice

DOACs are a simple, effective, safe, and cost-effective treatment for acute PE. The sPESI is a validated tool for identifying low-risk acute PEs for possible outpatient treatment. However, is it possible to combine these two concepts? Can low-risk PE patients be safely treated by initiating a DOAC in the ED and then discharging the patient to outpatient follow-up? This study provides further support towards the momentum that is already headed in that direction.

Anecdotally, this strategy is already being used by some ED providers in the United States (Beam 2015).

Of course, further evidence is needed prior to broader acceptance of such a strategy. The MERCURY-PE study was announced in 11/2016 to explore this very question. It will be a multicenter, prospective cohort study of the safety and efficacy of outpatient management of low-risk PE patients in the ED with rivaroxaban after application of the HESTIA risk stratification score.

Bottom Line

The use of rivaroxaban in patients with PE does not appear to increase the risk of averse events in comparison to the combination of enoxaparin and a VKA.

Read More

Read More

Pulm CCM: Oral Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) noninferior to warfarin for PE (RCT)

REBEL EM: Rivaroxaban for Treatment of Symptomatic Pulmonary Embolism

The SGEM: SGEM #126: Take Me to the Rivaroxaban – Outpatient Treatment of VTE

References

Agnelli G et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. NEJM 2013; 369(9): 799-808. PMID: 23808982.

Aujesky D et al. Outpatient versus inpatient treatment for patients with acute pulmonary embolism: an international, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2011; 378(9785): 41-48. PMID: 21703676

Beam DM et al. Immediate Discharge and Home Treatment With Rivaroxaban of Low‐risk Venous Thromboembolism Diagnosed in Two US Emergency Departments: A One‐year Preplanned Analysis. Acad Emerg Med 2015; 22(7): 788-795. PMID: 26113241.

EINSTEIN-PE Investigators. Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. NEJM 2012; 366(14): 1287-97. PMID: 22449293

Hokusai-VTE Investigators. Edoxaban versus warfarin for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism. NEJM 2013; 369(15): 1406-1415. PMID: 23991658.

Kahler ZP et al. Cost of treating venous thromboembolism with heparin and warfarin versus home treatment with rivaroxaban. Acad Emerg Med 2015; 22(7): 796-802. PMID: 26111453.

Konstantinides SV et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2014; 35(43): 3033-69. PMID 25173341

Schulman S et al. Treatment of acute venous thromboembolism with dabigatran or warfarin and pooled analysis. Circulation 2014; 129(7): 764 –772. PMID: 24344086.

Singer AJ et al. Multicenter trial of rivaroxaban for early discharge of pulmonary embolism from the emergency department (MERCURY PE): rationale and design. Acad Emerg Med 2016; 23(11): 1280-1286. PMID: 27537530

Zondag W et al. Outpatient versus inpatient treatment in patients with pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Eur Resp J 42.1 (2013): 134-144. PMID: 23100493