Background

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACE-I) are prescribed to millions of patients in the US. Though they are relatively safe, upper airway angioedema is one of the life-threatening adverse effects that we see frequently in the Emergency Department. Though this disorder is routinely treated with medications for anaphylaxis (i.e. epinephrine, histamine blockers, corticosteroids) the underlying mechanism of action predicts that these medications will fail. There is no well established treatment algorithm other than airway control if the angioedema is severe and appears to be causing a mechanical obstruction and cessation of the medication. A 2015 phase 2 study published in the NEJM touted the role for Icatibant in the treatment of these patients. Despite being heralded as “the cure,” the data set in this article was small questioning the validity of the findings. Enter the CAMEO study which attempts to further elucidate the benefits of this medication.

Clinical Question

Does the administration of icatibant to patients with ACE-I induced angioedema improve outcomes?

Population

Patients >/= 18 years of age who were being treated with an ACE-I and presenting with ACE-I induced angioedema of the head and/or neck within 12 hours of symptom onset.

Intervention

Icatibant 30 mg subcutaneous

Control

Placebo subcutaneous injection

Outcomes

Primary: Time to meeting discharge criteria “defined as time from study drug administration to earliest time that difficulty breathing and difficulty swallowing were absent and voice change and tongue swelling were mild or absent.”

Secondary: Occurrence of airway intervention, admission to hospital, use of corticosteroids, antihistamines or epinephrine and number/proportion of subjects meeting the primary endpoint at 4, 6 and 8 hours post-drug administration.

Design

Multinational (4 countries), multicenter (59 centers) randomized, double-blind clinical trial.

Excluded

The need for emergency airway intervention. Patients with non-ACE-I induced angioedema (i.e. hereditary angioedema, allergic angioedema, acquired angioedema), anaphylaxis, trauma, abscess or infection, local tumor, postoperative/postradiogenic edema, salivary gland disorders, acute urticaria.

Primary Results

- 147 patients screened and 121 patients included in the study

- 118 patients received treatment a median of 7.8 hours from symptom onset

Critical Findings

Critical Findings

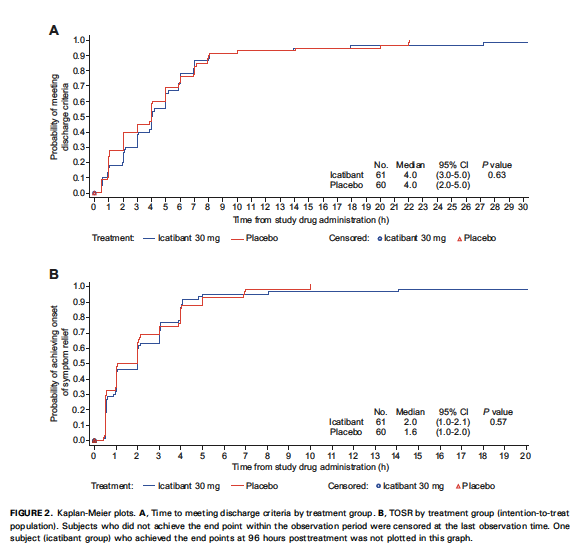

- Primary Endpoint (time to discharge)

- Median time to discharge in both groups: 4.0 hours

- No statistically significant difference

- Secondary Endpoints

- Airway Intervention

- One patient in icatibant arm required an airway intervention (none in placebo arm)

- No significant difference between treatment arms

- Hospitalization: 45.8% vs. 45.8% (No significant difference between treatment arms)

- Use of adjunct medications: 58.3% vs. 60.3% (No significant difference between treatment arms)

- Stratified Time to Discharge: No significant difference between treatment arms at any point (4, 6 or 8 hours)

- Airway Intervention

Strengths

- Study asks a clinically relevant, patient centered question. Instead of time to full resolution, the researchers looked at time to appropriate discharge (real-world assessment)

- Largest study examining question (Bas 2015 had n = 27)

- Randomization and blinding appropriately performed

- Multicenter, multinational protocol increases external validity of results

Limitations

- Diagnostic criteria to ensure ACE-I induced-angioedema are subjective (i.e. patients with other etiologies of angioedema may have been included)

- Time from onset of symptoms to drug administration was long (~ 8 hours)

- Majority of study participants Black or African American (Bas 2015 primarily European White). This must be considered when applying to another population

- The study excluded patients who required immediate airway management (couldn’t consent)

- Majority of patients had moderate symptoms

- Icatibant causes a local reaction at the injection site (twice as likely as with placebo in this trial) which may have led to some unblinding

Other Issues

- The study was funded by Shire HGT (maker of Icatibant) and employees of the sponsor were involved in design, collection, analysis and interpretation.

- It is laudable that the authors published these negative results. However, it is odd that the smaller, positive phase II trial was published in a major journal (NEJM) and the larger, negative phase III trial was published in a journal with a significantly smaller readership. This publication imbalance requires further thought and investigation.

Author's Conclusions

“Icatibant was no more efficacious than placebo in at least moderately severe ACE-I-induced angioedema of the upper airway”

Our Conclusions

We agree with the author’s conclusions. This well done, RDCT shows no benefit to the addition of icatibant in the treatment of ACE-I-induced angioedema.

Potential Impact To Current Practice

The excitement of some for the purported benefits of icatibant for this indication based on the small NEJM study was unfounded. Currently, there is no reason to add icatibant in the treatment of ACE-I induced angioedema.

Bottom Line

ACE-I induced angioedema remains a disorder without a viable treatment modality for reduction of symptoms. For now, the primary therapeutic interventions remain the same – airway management when indicated and removal of the offending agent.

Read More

Read More

EM Lit of Note: Icatibant . . . Can’t?

Pharm ER Tox Guy: No Icatibant for ACE-I Induced Angioedema

St. Emlyn’s: Icatibant for ACE Inhibitor Induced Angio-Oedema

EM: RAP: The Inside Scoop on Icatibant

The SGEM: Icatibant Bites the Dust – For ACE-I Induced Angioedema

References

Bas M et al. A randomized trial of icatibant in ACE-Inhibitor-Induced Angioedema. NEJM 2015; 372(5): 418-25. PMID: 25629740