Background

CT scans are frequently done after minor head injury to evaluate for intracranial hemorrhage. While CT scans are an excellent tool for diagnosing or ruling out this disorder, they are not without harms including radiation exposure, cost and department delays. Much of the time, CTs are negative, or find injuries for which no intervention is ever done and do not clinically affect the patient. Decision instruments may aid clinicians in determining which injuries are higher risk and require imaging and which do not.

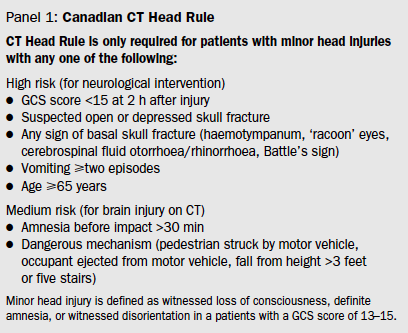

For the purpose of this study, minor head injury was defined as witnessed LOC, definite amnesia, or witnessed disorientation in a patient with a GCS of 13-15.

Clinical Question

Can a clinical decision instrument safely determine which patients with minor head injury do not need advanced imaging?

Population

Adult patients presenting to the emergency departments at 10 large Canadian hospitals with Glascow Coma Scale 13 or greater within 24 hours after blunt head trauma resulting in witnessed loss of consciousness, amnesia, or witnessed disorientation.

Intervention

Standardized clinical assessments were performed on all consecutive eligible patients before performing a CT scan at the discretion of the attending physician.

Control

Comparison: They took all the pre-CT variables and compared them with the CT and outcomes at 14 days looking for associations. From there they selected the combination of variables that would give the highest sensitivity/specificity for detecting the outcome measures using logistic regression and recursive partitioning. Overall, 44 variables were assessed (24 primary and 20 created by cut-offs/combinations)

Outcomes

Primary:Need for neurological intervention, defined as death within 7 days due to the head injury or need with 7 days for craniotomy, elevation of skull fracture, intracranial pressure monitoring, or intubation for head injury

Secondary:Clinically important brain injury on CT, defined as any acute brain finding on CT that would normally require admission to a hospital and neurological follow-up.

Design

Multicetner, prospective, cohort study.

Excluded

• Age under 16

• Minimal head injury with no LOC, amnesia, or disorientation

• Unclear history of trauma as the primary event (ie primary seizure or syncope)

• Obvious penetrating skull injury or depressed fracture

• Acute focal neurological deficit

• Unstable vital signs associated with major trauma

• Seizure prior to ED assessment

• Anticoagulation or bleeding disorder

• Pregnancy

Primary Results

- 3121 patients were enrolled and assessed for the primary outcome measure, need for neurological intervention.

- Initial GCS was 15 in 80% of patients.

- 2078 were scanned (67%) meaning 1043 were not scanned (33%)

- A decision tool was created including 7 variables formed through logistic regression followed by recursive partitioning.

Critical Findings

- Primary Outcome: High-risk criteria 100% sensitivity and 68.7% specificity to identify need for neurological intervention

- There were 44 patients (1%) who needed neurosurgical intervention

- All 44 were identified by this tool

- Secondary Outcome: Sensitivity and specificity of the overall rule (all 7 variables) were 98.4% and 49.6%.

- There were 254 patients (8%) were judged to have a clinically important brain injury.

- The tool identified 250 of the 254 cases.

The four patients not identified with the tool were small contusions. None required neurosurgical treatment and none had neurological sequelae.

Strengths

- Large, multicenter trial

- Study asked a clear clinical question that was patient centered

- Outcome measures were objective reducing bias

Limitations

- 33% of patients in the study did not have CT performed

- Although phone follow up was complete on those patients not getting CT in the ED, follow up only went out to 14 days

Author's Conclusions

“We have developed the Canadian CT Head Rule, a highly sensitive decision rule for use of CT. This rule has the potential to significantly standardise and improve the emergency management of patients with minor head injury.”

Our Conclusions

This was a high-quality study with a good sample size. The final decision instrument had excellent sensitivity for detecting clinically relevant intracranial injuries (defined here as requiring neurosurgical intervention) but even the expanded rule will miss a small portion of patients with identifiable intracranial injuries (although not clinically significant ones).

Subsequent studies have compared the New Orleans and Canadian head CT decision instruments (Papa 2012, Smits 2005) and found that both rules perform with 100% sensitivity for finding injuries that require neurosurgical intervention. The New Orleans criteria perform better for finding all injuries but, as a result, have much lower specificity. Smits et al estimated that adoption of the New Orleans rule would result in a modest 3% reduction in CT utilization while adoption of the Canadian head CT instrument would result in a 37.3% reduction (Smits 2005).

Potential Impact To Current Practice

This decision instrument continues to be widely used today by clinicians to help guide decision-making in minor head injuries. This article was named one of ALiEM’s Landmark Articles.

Bottom Line

The Canadian Head CT decision instrument is a highly sensitive tool for determining which patients with minor head injury do not need emergent advanced imaging performed.

Read More

Papa L et al. Performance of the Canadian CT head rule and the New Orleans criteria for predicting any intracranial injury on computed tomography in a United States Level I trauma center. Acad Emerg Med 2012; 19(1): 2-10. PMID: 22251188

Smits M et al. External validation of the Canadian CT head rule and the New Orleans criteria for CT scanning in patients with minor head injury. JAMA 2005; 294(12): 1519-25. PMID: 16189365

SGEM #106: O Canada – Canadian CT Head Rule for Patients with Minor Head Injury

See Also Core EM Post on the New Orleans’ Head CT Criteria