Definition: Pain caused by the presence of a stone in the urinary tract (urolithiasis)

Epidemiology

- Common clinical problem affecting 5-15% of the population

- Recurrence rate up to 50% (Moe 2006)

- Most commonly seen in young men aged 20-50

Pathophysiology

- The majority of stones are formed in the kidney and then move into the ureter

- Stone types

- Calcium oxalate (75%)

- Typically result from hypercalciuria from hyperexcretion

- Causes: hyperparathyroidism, exogenous calcium intake (i.e. antacids)

- Magnesium-ammonium-phosphate (struvite) stones (15%)

- Result from urinary tract infection with urea-splitting organisms (Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Providencia and Proteus species)

- Uric acid stones (5-10%)

- Caused by hyperexcretion of uric acid

- Tend to be radiolucent

- Cystine stones (1-2%)

- Calcium oxalate (75%)

- Pain is caused by the passage of the stone through the ureter, bladder and urethra. Calculi within the kidney do not cause pain

- Stones that obstruct the collecting system cause hydronephrosis

Presentation

- Pain is the hallmark feature of ureteral colic

- Typically sudden onset of pain with a rapid crescendo

- Usually sharp in nature and may come in waves (intermittent)

- Originates in the flank and radiates around the abdomen to the testicle (men) or labia majora (women)

- Dysuria is common

- Nausea and vomiting are common

- Gross hematuria is present in about 1/3 of patients. Rarely, patients may present with painless hematuria

- Physical Examination

- Patients are typically very uncomfortable and have difficulty lying still. They often will writhe in pain.

- Abdominal examination rarely reveals any significant tenderness on palpation. In the presence of significant tenderness, alternate diagnoses should be sought

- Look for a pulsatile abdominal mass on abdominal examination which may reveal an alternate diagnosis (abdominal aortic aneurysm)

- The presence of a fever should alert the clinician to the possibility of infection (i.e. UTI)

Differential Diagnosis

- Urinary tract infection (UTI)

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm (or dissection)

- Renal artery thrombosis (renal infarction) or dissection

- Acute appendicitis

- Testicular torsion

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Ruptured ovarian cyst

- Herpes Zoster

Diagnostics

- Goal: Ureteral colic is a clinical diagnosis. The goal of diagnostic tests is not to confirm the presence or absence of a ureteral stone but rather to exclude other more serious causes of the patient’s symptoms.

- Urinalysis

- Hematuria (gross or microscopic) is seen in the majority (70-90%) of but not all patients (its absence does not rule out urolithiasis)

- Pyuria (presence of WBCs)

- Concomitant UTI should be considered when WBCs are present AND if the patient has other concerning

KUB with Stone (commons.wikimedia.org)

symptoms (fever, chills, dysuria)

- Can result from inflammation without infection

- Concomitant UTI should be considered when WBCs are present AND if the patient has other concerning

- Imaging

- Imaging to confirm the presence of a ureteral calculus is frequently unnecessary in the ED (even for first-time stones). If the clinical presentation is consistent with ureteral colic, the patient does not have any significant concerning signs or symptoms (i.e. infected stone, refractory pain) and alternate dangerous diagnoses are unlikely, imaging can be avoided during the primary presentation.

- KUB (Kidney, Ureter and Bladder) X-ray

- 90% of stones are radiopaque

- Other structures can confuse findings on X-ray (phleboliths and calcified lymph nodes have a similar appearance)

- Often used by urologists to track the progress of stones through the ureter

- Limited utility in isolation in the ED, though may be combined with US

- Ultrasound (US)

- An US-first approach appears reasonable (Smith-Bindman 2014)

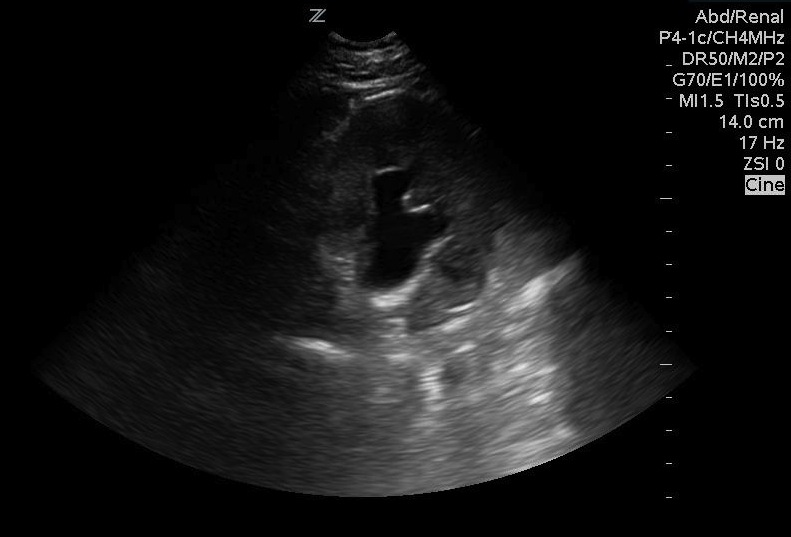

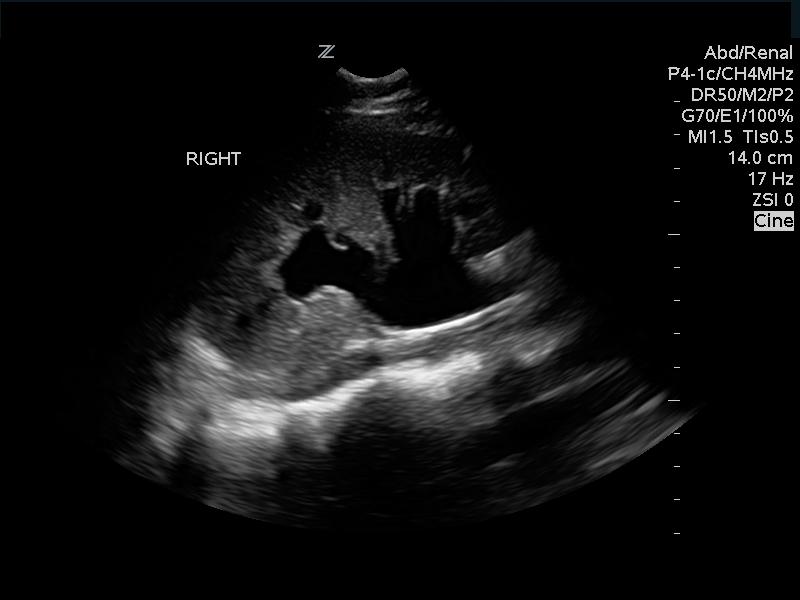

Moderate Hydronephrosis

- Multicenter, randomized trial

- Sensitivity US-first: 54%

- Low rate of missed serious diagnoses compared to CT-first approach: 0.5% vs. 0.3%

- 41% of US-first approach patients underwent CT

- US-first approach patients received 40% less radiation over next 6 months

- Test characteristics of US depend on diagnostic criteria: direct visualization of a stone, unilateral hydronephrosis or both

- Combined criteria: Sensitivity 85%, Specificity 100% (Sinclair 1989)

- Direct visualization of stone: Sensitivity 37-64%, Specificity 100% (Sinclair 1989)

- Hydronephrosis:

Moderate Hydronephrosis

- Any hydronephrosis: Sensitivity/specificity in 70% range (Herbst 2014)

- Obstructing hydronephrosis: sensitivity 85%, Specificity 100% (Sinclair 1989)

- There is excellent agreement among emergency physicians about the degree of hydronephrosis (k=0.85), and the degree of hydronephrosis predicts stone size (Goertz 2015)

- A normal renal US predicts patients with renal colic at low risk for urologic intervention (Yan 2015)

- Ureteric Jet

- Flow of urine into the bladder. Normally should be seen bilaterally, > 2 jets every minute (Wu 2010)

- Unilateral absence of a ureteric jet indicates obstruction of the ureter (Nicolau 2015)

- The presence of bilateral jets does NOT rule out the presence of a ureteric stone

- US can also be used to look for alternate diagnoses (i.e. AAA)

- US evaluation does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation

- An US-first approach appears reasonable (Smith-Bindman 2014)

- CT Scan

- CT need not be performed in all patients with ureteral colic symptoms as it exposes patients to ionizing radiation and increases health care costs (Firestone 2014)

- Superior diagnostic characteristics (Smith 1996, Pfister 2003)

- Sensitivity: 97%

- Specificity: 96 – 100%

- Added benefit of ability to identify other pathology: malignancy, AAA, renal abscess

Indications for CT: Concern for infected stone (with or without obstruction), concern for alternate serious diagnosis (especially in elderly patients), solitary kidney - Typically performed without IV contrast as almost all stones are visible

- IV contrast may be helpful in differentiating distal ureteral stones from pelvic phleboliths, and may also aid in the evaluation of infection as well as alternate diagnoses

Management:

- Supportive Care

- Pain control

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- First-line agents for pain control

- Superior reduction in pain in comparison to opiates (Pathan 2016)

- Often require parenteral administration secondary to nausea and vomiting but if patient will tolerate PO, can give an oral NSAID

- Parenteral NSAID options

- Ketorolac: 15 mg IV or 30 mg IM

- Diclofenac: 75 mg IM

- Opioids

- May be used as adjunctive therapy to NSAIDs

- Lower efficacy in comparison to NSAIDs or IV acetaminophen (Pathan 2016)

- Higher rate of side effects than NSAIDs or acetaminophen

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Antiemetics

- IV fluids

- No evidence to defend routine use of fluids (Worster 2012)

- Reasonable intervention if patient has signs of volume depletion

- Pain control

- Infected Ureteral Stone

- Patients who are well-appearing without significant hydronephrosis can be discharged home on oral antibiotics if they are tolerating oral intake

- Patients with significant hydronephrosis, obstruction, ill-appearance or inability to tolerate oral intake should be started on parenteral antibiotics and have consultation with urology (Wang 2016)

- Presence of an obstructing stone with accompanying sepsis should be treated with immediate urinary collecting system decompression (i.e. nephrostomy tube or ureteral stent) (Preminger 2007)

- Medical Expulsive Therapy (MET)

- Theory: administration of pharmacologic agents (alpha1-antagonists (i.e. tamsulosin) or calcium channel blockers (i.e. nifedipine)) relaxes ureteral smooth muscle and facilitates stone passage resulting in both decreased pain and need for surgical intervention

- Despite signs of benefit from early studies, an extensive literature review reveals no significant benefit for MET (Swaminathan 2014)

- A large, high-quality RDCT in 2015 showed no benefit for MET with either tamsulosin or nifedipine (Pickard 2015)

- For a very specific subset of patients, however, with larger (5-10 mm) distal stones, tamsulosin may improve rates of stone passage (Furyk 2016)

Disposition:

- Presence of an obstructing stone with signs/symptoms of a UTI should prompt urology consultation and admission for parenteral antibiotics and possible urinary diversion (e.g. percutaneous nephrostomy tube or ureteral stent placement)

- Most patients can be discharged home if they are able to tolerate oral medications and their pain is controlled

- Patients with refractory pain, nausea and vomiting should be considered for observation

Take Home Points

- The diagnosis of ureteral colic is based on clinical evaluation. Patients with a high suspicion for urolithiasis and a low suspicion for alternate diagnoses can be treated empirically and may not require a confirmatory CT scan

- If the patient with ureteral colic presents with fever and pyuria/bacteriuria, suspect an infected stone. Treat with antibiotics, obtain imaging and consult urology

- The cornerstone of management in the majority of patients with ureteral colic is pain control. NSAIDs are first line and MET should not routinely be prescribed based on high-quality evidence, though may be considered in large, distal ureteral stones

Read More

Core EM: Medical Expulsive Therapy (MET) in Renal Colic

Core EM: Podcast 51.0: Analgesia in Renal Colic

REBEL EM: Does Use of Tamsulosin in Renal Colic Facilitate Stone Passage?

ALiEM: Top 10 reasons NOT to order a CT scan for suspected renal colic

Ban KM, Easter JS: Selected Urologic Problems, in Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al (eds): Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, ed 8. St. Louis, Mosby, Inc., 2010, (Ch) 99: p 1326-1356.

References

Firestone D. (2014, April 10). Top 10 reasons NOT to order a CT scan for suspected renal colic [ALiEM]. Retrieved from http://www.aliem.com/2014/top-10-reasons-order-ct-scan-suspected-renal-colic/

Furyk JS, et al. Distal Ureteric Stones and Tamsulosin: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized, Multicenter Trial. Ann Emerg Med 2016; PMID 26194935

Goertz JK, Lotterman S. Can the degree of hydronephrosis on ultrasound predict kidney stone size? Am J Emerg Med 2010; 28(7): 813-6. PMID: 20837260

Herbst MK. Effect of provider experience on clinician-performed ultrasonography for hydronephrosis in patients with suspected renal colic. Ann Emerg Med 2014; PMID: 24630203

Moe OW. Kidney stones: pathophysiology and medical management. Lancet 2006; 367: 333-344. PMID: 16443041

Nicolau C et al. Imaging patients with renal colic – consider ultrasound first. Insights Imaging 2015; 6(4): 441-7. PMC 4519809

Pathan SA et al. Delivering safe and effective analgesia for management of renal colic in the emergency department: a double-blind, multi group, randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2016. PMID: 26993881

Preminger GM et al. 2007 Guideline for the management of ureteral calculi. J Urol. 2007;178: 2418-2434. PMID: 17993340

Pfister SA et al. Unenhanced helical computed tomography vs. intravenous urography in patients with acute flank pain: Accuracy and economic impact in a randomized prospective trial. Eur Radiol 2003; 13:2513. PMID: 12898174

Pickard R et al. Medical expulsive therapy in adults with ureteric colic: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 386(9991): 341-9. PMID: 25998582

Sinclair D, et al. The evaluation of suspected renal colic: ultrasound scan

vs excretory urography. Ann Emerg Med 1989;18:556–9. PMID: 2655508

Smith RC et al. Diagnosis of acute flank pain: value of unenhanced helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996;166:97–101. PMID: 8571915

Smith-Bindman, et al. Ultrasonography versus computed tomography for suspected nephrolithiasis. NEJM 2014; 371(12): 1100-10. PMID: 25229916

Swaminathan A. (2014, August 7). Does Use of Tamsulosin in Renal Colic Facilitate Stone Passage? [REBEL EM]. Retrieved from http://rebelem.com/use-tamsulosin-renal-colic-facilitate-stone-passage/

Wang RC. Managing Urolithiasis. Ann Emerg Med 2015 PMID: 26616536

Worster AS, Bhanich Supapol W. Fluids and diuretics for acute ureteric colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(2): CD004926. PMID: 22336806

Wu CC. Ureteric Jet. J Med Ultrasound 2010; 18: 141-6. OPEN ACCESS

Yan JW, et al.Normal renal sonogram identifies renal colic patients at low risk for urologic intervention: a prospective cohort study. CJEM 2015; 17(1): 38-45. PMID: 25781382