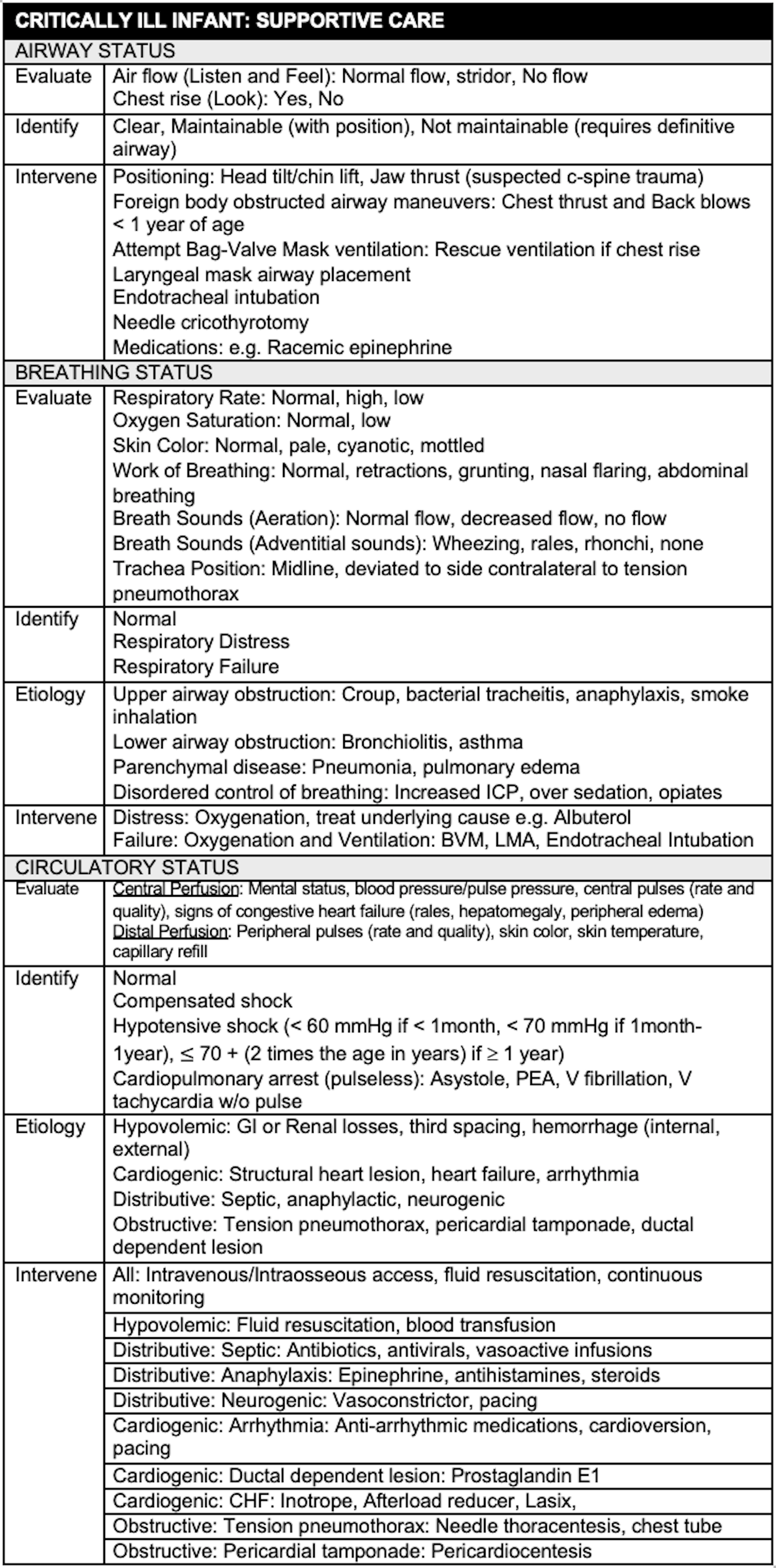

INTRODUCTION

- The critically ill infant is thankfully a rare event

- Limited clinical exposure to these patients heightens anxiety and limits the development of a structured approach to their care

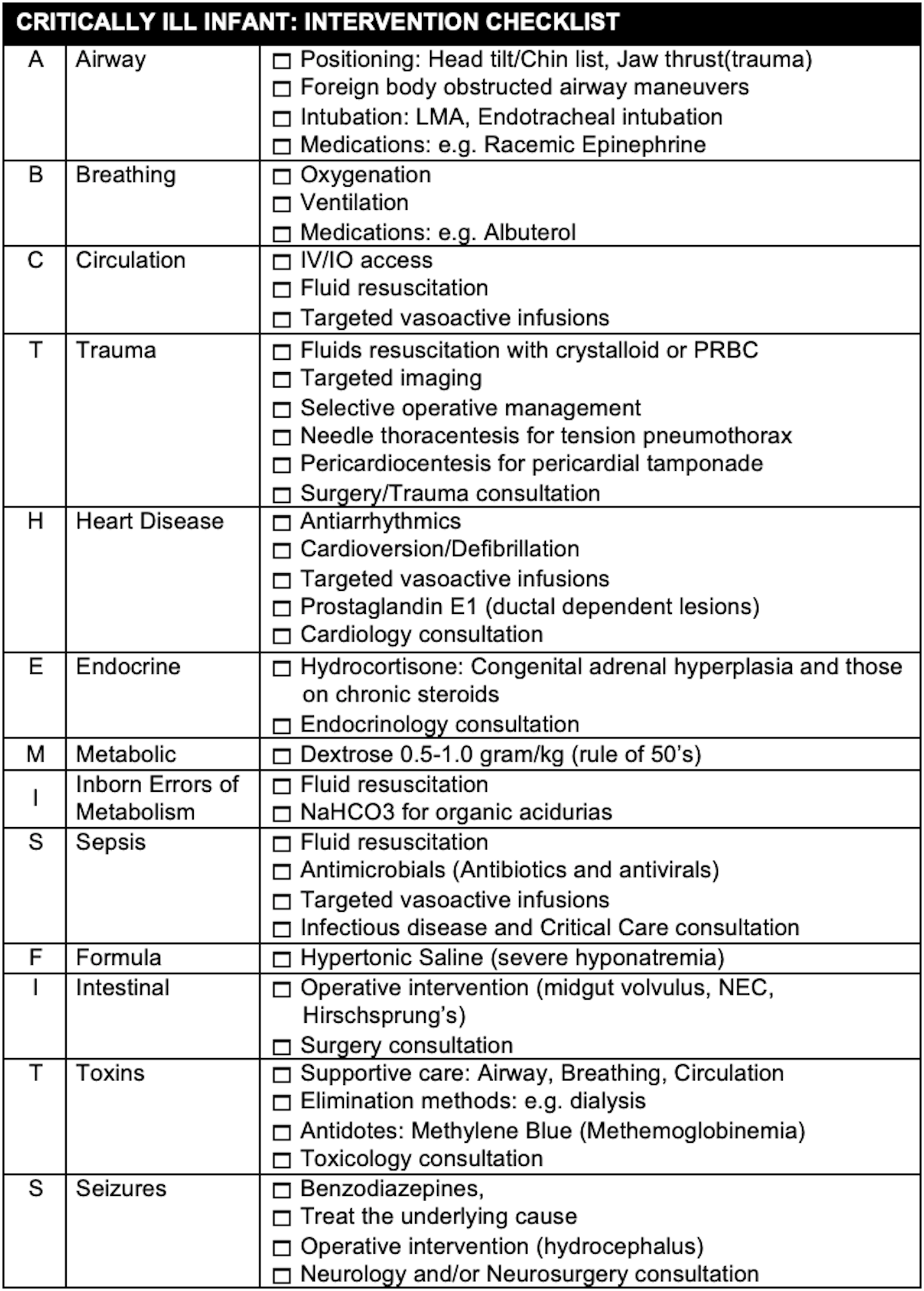

- The goal is to develop a checklist for both supportive care and specific interventions than can make a difference in the first hour of care

- Focus on the disease processes that are readily identifiable in the ED and are associated with successful interventions

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

- The differential diagnosis is extensive, including both congenital and acquired diseases. The younger the infant the higher the likelihood of congenital disease.

- The general categories of illness that can occur can be remembered with the mnemonic: THE-MISFITS.

TRAUMA

- Unique anatomic and physiologic differences result in injury patterns different from adults

- Non-accidental trauma should be considered in every critically ill infant as a clear history of trauma may not be present. A focused assessment of external signs of trauma (bruising, frenulum tear, retinal hemorrhage) and signs of structural neurologic disease (fixed dilated pupil, seizures, bulging fontanel, posturing) may be the only clue to a traumatic brain injury

HEART DISEASE

- May include structural congenital heart disease (e.g. Tetralogy of Fallow) and acquired heart disease (arrhythmias, myocarditis)

- Signs and symptoms are often nonspecific such as poor feeding, vomiting or decreased activity level

- Ductal dependent cardiac lesions may present with an acute onset of deterioration when the ductus closes

- The right-sided ductal dependent lesions typically present with cyanosis

- The left sided ductal dependent lesions typically present with signs of congestive heart failure such as trouble feeding, breathing, sweating, irritability, rales, hepatomegaly, weak or absent pulses and signs of poor distal perfusion

- Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) should be used immediately to maintain or reopen a patent ductus arteriosus. The primary adverse events after prostaglandin are apnea and hypotension

- Arrhythmias are relatively rare in the child. The most common prearrest rhythms are supraventricular tachycardia and sinus bradycardia. The most common arrest rhythm is asystole. Approximately 10% of arrest rhythms are ventricular

ENDOCRINE

- The primary endocrine problem in the neonate is adrenal insufficiency due to congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)

- Acute salt loosing crises of CAH typically presents between 3-5 weeks of age with nonspecific symptoms of altered mental status and shock

- Physical examination findings may include skin hyperpigmentation due to increased ACTH secretion and ambiguous genitalia (cliteromegaly in females) due to the increased production of androgens by alternative pathways

- Characteristic electrolyte abnormalities include: hyponatremia and hyperkalemia due to mineralocorticoid deficiency and metabolic acidosis and hypoglycemia due to glucocorticoid deficiency

- The primary treatment of CAH is circulatory support and the administration of hydrocortisone (has both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid activity

METABOLIC

- The primary metabolic disease not included in the other categories of the mnemonic is hypoglycemia

- The presentation of hypoglycemia is nonspecific including central nervous symptoms signs such as seizures and altered mental status and signs of adrenergic excess such as tachycardia and diaphoresis

- The differential diagnosis of hypoglycemia in the infant is extensive including: sepsis, inborn errors of metabolism and multiple toxins (e.g. ethanol, beta blockers, salicylates and sulfonylureas)

- A bedside glucose should be obtained in all critically ill infants

- Dextrose is administered as in a concentration of D10 in the neonate and young infant and D25 in the older infant and child. The rule of 50’s can be used to deliver 0.5 gram/kg of Dextrose (# ml/kg x dextrose concentration = 50, e.g. 5 ml/kg x D10, 2 ml/kg x D25)

INBORN ERRORS OF METABOLISM

- The presentation of an inborn error is nonspecific and overlaps considerably with other childhood disease so a high index of suspicion is warranted. A family history of unexplained infant deaths or consanguinity can contribute to the diagnosis

- The most common findings are neurologic (ranging from irritability to coma), and gastrointestinal complaints

- Management is primarily supportive followed by efforts to remove toxic metabolites and decrease production of toxic intermediaries by preventing catabolism and promoting anabolism

- Organic acidurias are primarily identified by a profound anion gap metabolic acidosis. Hypoglycemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and a mild hyperammonemia may be seen.

- Management of organic acidurias include: fluid resuscitation, correction of acidosis with NaHC03, and dextrose to correct hypoglycemia and promote anabolism

- Urea cycle defects are identified by a marked hyperammonemia and elevated liver transaminases in the absence of a profound metabolic acidosis

- Management includes efforts to decrease ammonia production such as dextrose to correct hypoglycemia and promote anabolism and oral neomycin to prevent bacterial ammonia production. Efforts to increase ammonia excretion include: fluid resuscitation, dialysis or exchange transfusion and the use of nitrogen scavengers such as sodium benzoate and sodium phenylacetate.

SEPSIS

- Infection is the leading cause of critical illness in this population

- Fever or hypothermia, altered mental status, respiratory distress and signs of inadequate perfusion are hallmarks of sepsis but are non-specific

- Unless a definitive alternative diagnosis is identified all critically infants should receive appropriate antimicrobials (antibiotics and antivirals)

- Typically, this includes a:

- 3rd generation cephalosporin such as Ceftriaxone (gram negative coverage (Cefotaxime if less than 6 weeks of age)

- Vancomycin (gram-positive coverage)

- Acyclovir (HSV)

- Typically, this includes a:

FORMULA

- Formula is included in the mnemonic for the possibility of incorrectly mixed infant formula. The addition of too much water results in hyponatremia and the addition of too little water results in hypernatremia

- Hyponatremia is defined as a serum sodium of less than 130 meg/liter

- At sodium levels <120 mEq/L or with rapid declines in sodium, central nervous system signs and symptoms predominate. These include: seizures, altered mental status, hyporeflexia, pseudobulbar palsy, hypothermia and have Cheynes-Stokes respiration

- Management of hypovolemic hyponatremia states consists of careful fluid resuscitation to avoid rapid shifts in serum osmolality and osmotic demyelination. In patients with altered mental status or seizures, hyponatremia should be corrected quickly corrected with 3-5 ml/kg of hypertonic saline (3NS)

- Hypernatremia is defined as a serum sodium of greater than 150 meg/liter. It is rare in pediatrics but can be associated with significant neurologic deficits if severe or occurs rapidly

- Severe symptoms occur above 160 mEq/L. These include lethargy, coma, and seizures. In the most severe cases, brain shrinkage, results in vascular rupture with hemorrhage

- Management consists of careful fluid resuscitation to avoid rapid shifts in serum osmolality and osmotic demyelination and replacement of the free water deficit

INTESTINAL

- The surgical abdomen in the neonate is a rare event, but is associated with a very high morbidity and mortality. Intestinal obstruction, ischemia or perforation can quickly lead to severe dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, sepsis and irreversible intestinal damage

- Intestinal catastrophes include: malrotation with midgut volvulus, necrotizing enterocolitis with perforation and Hirschsprung’s disease with toxic megacolon

- Findings include bilious or bloody vomiting, abdominal distension and bloody stools.

- Appropriate imaging (abdominal XRAY, upper GI series, abdominal ultrasound) can confirm the diagnosis and need for operative intervention

- Early involvement of pediatric surgery and radiology is essential

TOXINS

- Medications typically associated with high mortality include: sulfonylureas, opioids, amphetamines and calcium and sodium channel blockers (chloroquine, tricyclic antidepressants, propranolol). Household agents typically included on this list include: ethanol (hypoglycemia), toxic alcohols, organophosphate and carbamate insecticides, hydrocarbons and camphor

- Management of most toxins is supportive. However, some toxins may benefits form efforts to eliminate it (activate charcoal, dialysis, alkalization) or from specific antidotes

- Early involvement of a toxicology consultant is essential (American Association of

- Poison Control Centers: 1-800-222-1222, NYC Poison Control Center: 1-212-POISONS (1-212-764-7667))

- Infants are at high risk for methemoglobinemia. NADH methemoglobin reductase is not fully active until 4 months of age and fetal hemoglobin is more readily oxidized

- Infants may develop methemoglobinemia from diarrhea, dehydration or sepsis. Premature infants, low birth weight infants and those with underlying hematologic or pulmonary disease are at increased risk.

- Methylene blue is indicated for patients with symptoms suggestive of oxygen deprivation which occur typically at methemoglobin levels > 20%

SEIZURES

- Neonates are at high risk of developing seizures related to CNS abnormalities (hydrocephalus) and metabolic disease (electrolytes, inborn errors of metabolism)

- A lumbar puncture and neuroimaging may be considered in the febrile child with signs of meningitis or localizing neurologic findings but should be deferred in the critically ill infant

- First line agents: Benzodiazepines can be administered by the intravenous, intraosseous, intramuscular, intranasal and buccal mucosa routes

- Second line agents include: Phenytoin, Fosphenytoin, Phenobarbital, Valproate and Levetiracetam

- Agents for refractory status epilepticus include infusions of Midazolam, Propofol and Pentobarbital

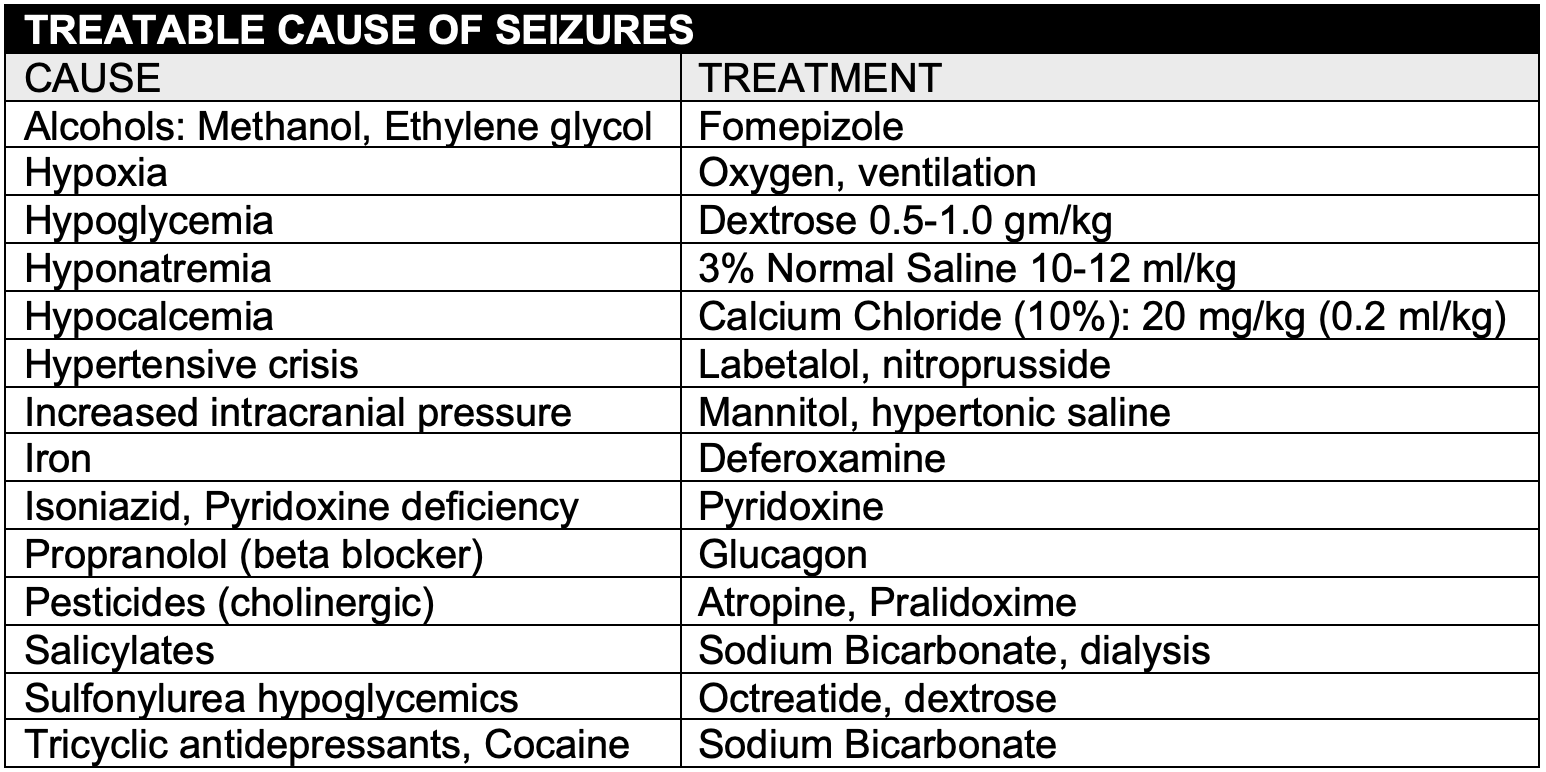

- The underlying causes of seizures should be identified and treated appropriately

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

- The younger the infant, the more limited their repertoire of daily activities. An infant eats and drinks, pees and poops, is awake and happy, awake and not happy or sleeping. A rapid history should focus on the disease impact on these activities as well as atypical symptoms.

- Common complaints typically associated with minor illness may mask a serious underlying disease. For example, the tachypneic infant during bronchiolitis season may have a severe metabolic acidosis from an inborn error of metabolism or have myocarditis.

- It is important to remember that focal signs and symptoms may represent systemic disease as well as disease in another organ system. For example, vomiting may be a sign of GI obstruction or increased intracranial pressure from hydrocephalus or intentional head trauma.

| COMMON SYMPTOMS ASSOCIATED WITH LIFE THREATENING ILLNESS | |

| Tachypnea | Metabolic Acidosis, salicylate ingestion |

| Tachycardia | Myocarditis, internal hemorrhage |

| Wheezing | Pulmonary edema, airway foreign body |

| Vomiting | Midgut volvulus, hydrocephalus |

| Constipation | Hirschsprung’s with toxic megacolon |

| Crying | Myocardial infarction from anomalous left coronary artery |

| Coughing | Tracheo-esophageal fistula, diaphragmatic hernia |

| Sleeping too much | Congestive heart failure, inborn error, hydrocephalus |

- The Pediatric Assessment Triangle can be used to quickly answer the question: Is this infant sick or not sick? It includes a rapid assessment of appearance, breathing and circulation. It can identify the primary pathology in order to target effective interventions. An abnormality in any phase warrants a more complete evaluation.

- Appearance: General indicator of level of consciousness including the degree of interactivity, muscle tone and verbal response or cry

- Breathing: Includes an evaluation of the patients positioning (e.g. tripod or sniffing), work of breathing and adventitial breath sounds

- Circulation: Overall circulatory status based on general color (pale, cyanotic, mottled)

MANAGEMENT

- Advanced preparation includes having the appropriate equipment and personnel available and trained in pediatric resuscitation and having procedures in place to escalate the level of care including transfer of the patient

- It is important to establish a weight for medication dosing and an age for equipment selection. This can be facilitated with the use of a weight-based resuscitation tape such as the Broselow tape

- Interventions include those intended as supportive care and disease specific interventions

- Early escalation to appropriate subspecialty consultants is essential

Very Informative, I will be using some information to put together a lecture on care of the critically Ill neonate for nurses pursuing the ICU speciality