Background: Patients with penetrating neck trauma can present with a variety of injury patterns including hemorrhagic shock, airway obstruction and neurologic injury. Serious injuries may not be clinically obvious making diagnosis and prompt treatment challenging. Due to the large number of critical structures in the neck, a clear knowledge of the anatomy is necessary for proper evaluation and management.

Epidemiology (Evans 2018)

- Represent 1% of all trauma admissions in the US and have a 5% mortality rate

- 80% of morality secondary to cerebral infarction

- ~ 20% of mortality secondary to uncontrolled hemorrhage

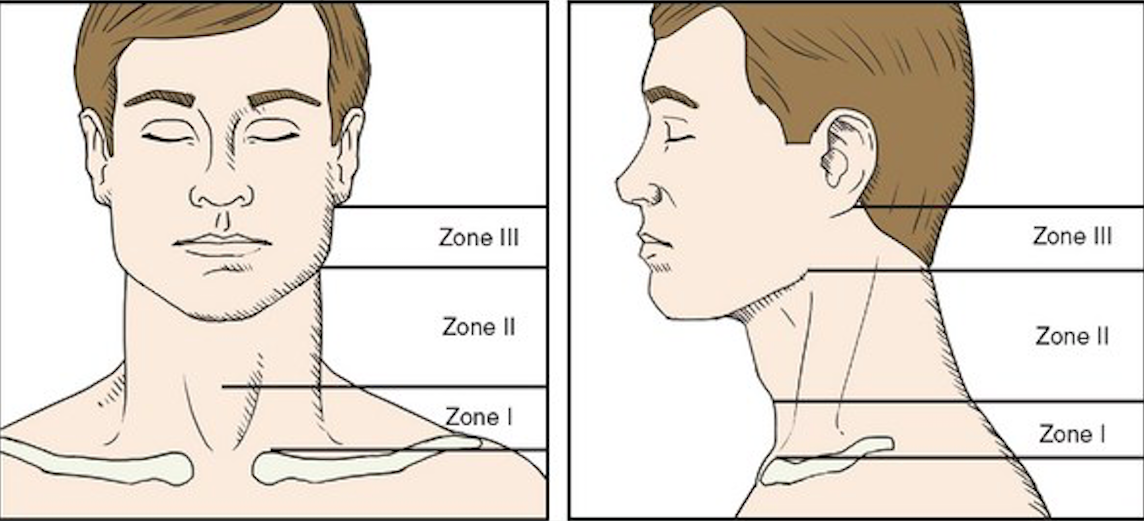

Zones of the Neck and Anatomical Structures

- The neck is classically divided into three zones

- Zone I: Clavicles/sternum to the cricoid cartilage

- Zone II: Cricoid cartilage to the angle of the mandible

- Zone III: Superior to the angle of the mandible to skull area

Neck Zones I (basicmedicalkey.com)

|

Zone 1 |

Zone 2 |

Zone 3 |

|

|

Anatomic Landmarks |

Clavicle/Sternum to Cricoid Cartlage |

Cricoid Cartilage to the Angle of the Mandible |

Superior to the Angle of the Mandible |

|

Anatomic Structures in Zone |

Proximal Common Carotid Artery |

Carotid Artery |

Vertebral Artery |

|

Subclavian Artery |

Vertebral Artery |

Distal Carotid Artery |

|

|

Vertebral Artery |

Jugular Vein |

Distal Jugular Vein |

|

|

Lung Apices |

Pharynx |

Salivary and Parotid Glands |

|

|

Trachea |

Trachea |

Cranial Nerves IX – XII |

|

|

Thyroid |

Esophagus |

Spinal Cord |

|

|

Esophagus |

Larynx |

||

|

Thoracic Duct |

Vagus Nerve |

||

|

Spinal Cord |

Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve |

||

|

Spinal Cord |

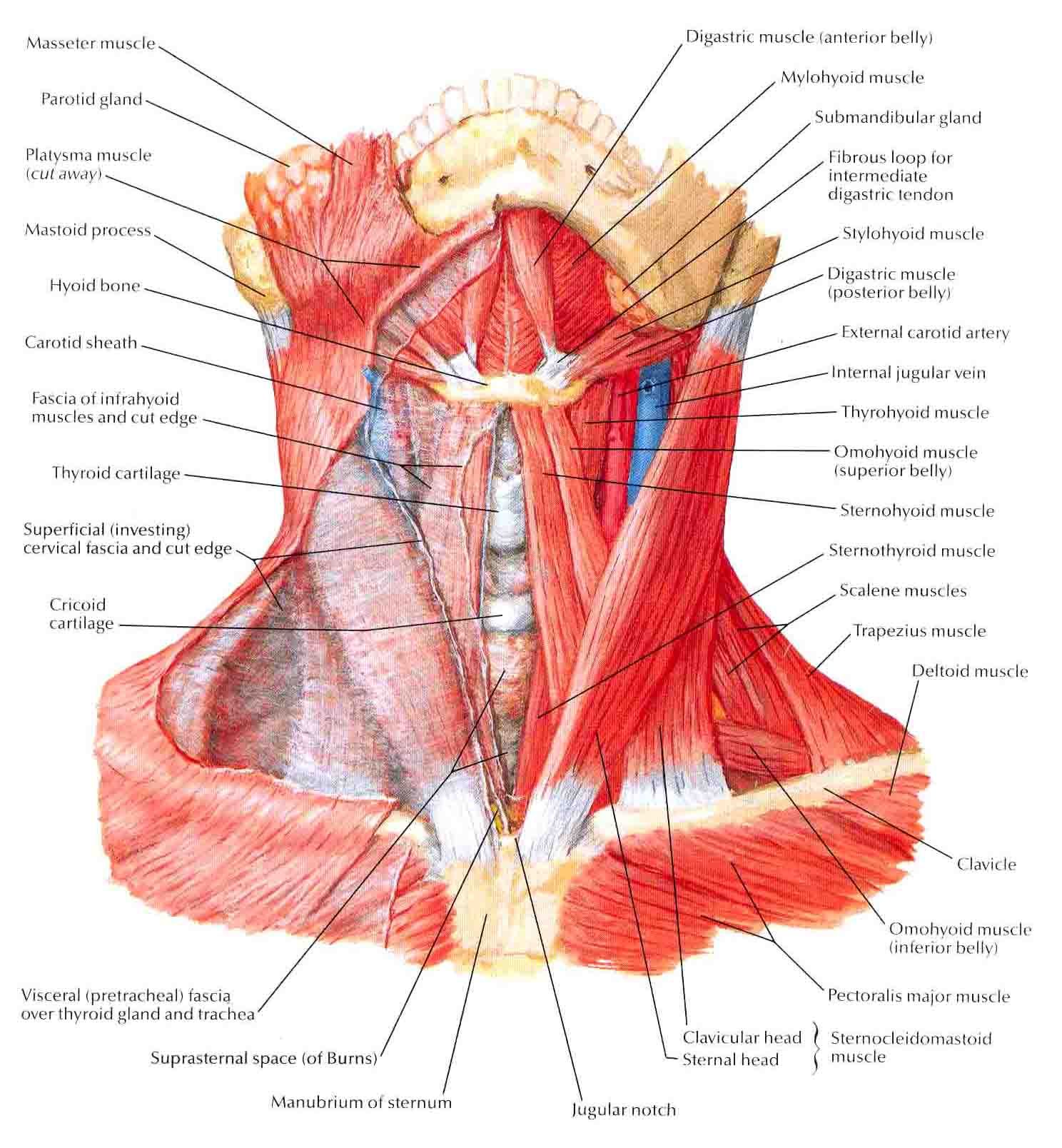

Neck Anatomy I (Netter’s)

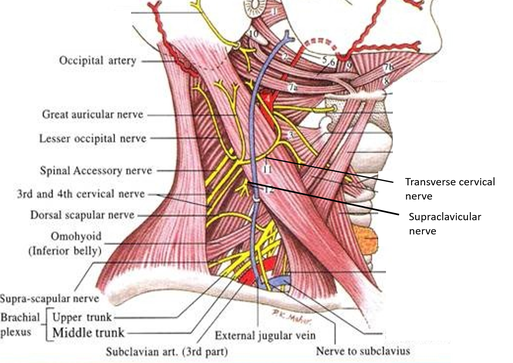

Posterior Triangle of the Neck Anatomy (anatomyqa.com)

- Zone system can be used to think about what structures may be injured but caution should be used as a penetrating injury can transverse zones

- Historically the zones were divided by easy accessibility for surgical exploration (Zone II) vs those that would likely need angiography to delineate vascular injury (Zones I, III)

- Other important anatomic features

- There is anatomic continuity in the fascial layers between the neck and the anterior mediastinum

- The platysma muscle sits between the superficial and deep cervical fascia: Violation of the platysma increases the likelihood of deep structure injury and should be explored in the operating room immediately.

Hard and Soft Signs of Major Aerodigestive or Neurovascular Injury (Sperry 2013)

|

Hard Signs |

Soft Signs |

|

Airway Compromise |

Hemoptysis |

|

Expanding or Pulsatile Hematoma |

Oropharyngeal Blood |

|

Active, Brisk Bleeding |

Dyspnea |

|

Hemorrhagic Shock |

Dysphagia |

|

Hematemesis |

Dysphonia |

|

Neurologic Deficit |

Nonexpanding Hematoma |

|

Massive Subcutaneous Emphysema |

Chest Tube Air Leak |

|

Air Bubbling Through Wound |

Subcutaneous or Metiastinal Air |

|

Vascular Bruit or Thrill |

|

|

Crepitus |

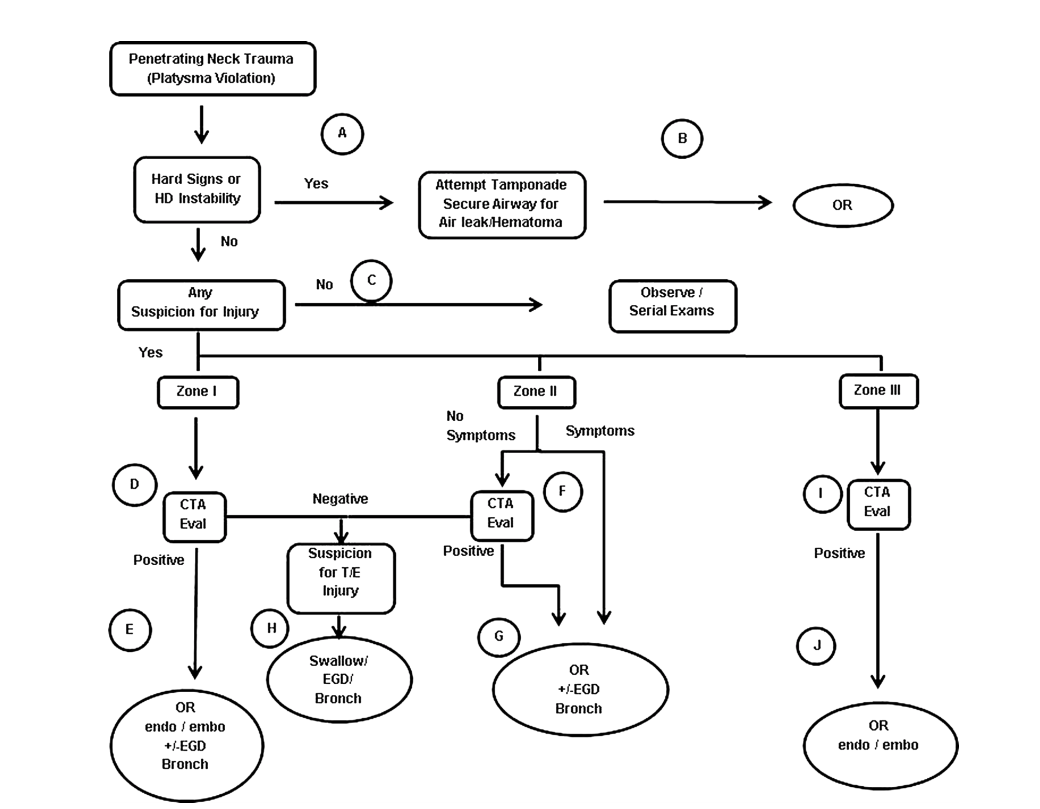

WTA Management Algorithm for Penetrating Neck Injury (Sperry 2013)

Management

- Basics + Initial Assessment

- Focus on immediate life-threats: exsanguination and asphyxiation from airway obstruction

- Any patient with hard signs of injury should be expeditiously brought to the operating room for further management

- Hard signs associated with 90% rate of major injury (Evans 2018)

- Delays should only occur for securing the unstable airway

- Can apply direct pressure to bleeding wounds en route

- Do not take these patients to CT scan

-

- Airway

- Tracheobronchial Injury occurs in up to 20% of patients (Kendall 1998)

- Early airway control should be considered in patients with hard signs

- Expanding hematomas can cause dynamic airway compromise

- Hematemesis and hemoptysis can make visualization of the airway structures challenging

- Have the neck prepared for front of neck access (i.e. cricothyroidotomy) if laryngoscopy or endotracheal tube placement fails

- Careful/gentle placement of the ETT is necessary when the patient has a partial transection of the trachea. Consider a smaller tube size to minimize secondary injury.

- Bag valve mask (BVM) ventilation should be minimized as it can cause dissection of air into the neck and worsen airway distortion

- Paralysis may theoretically cause airway obstruction by relaxation of muscles (though this is not born out in the literature). Consider awake intubation or ketamine facilitated intubation

- Cervical spine immobilization is unnecessary unless the trajectory suggests direct spinal cord injury and may be harmful (Vanderlan 2009, Haut 2010, Stuke 2011, Lustenberger 2011, Theodore 2013)

- Can obscure neck injuries

- Preclude an adequate assessment

- Make airway visualization more difficult

- Delay definitive airway stabilization

- Breathing

- Zone I injuries can result in pneumothorax (PTX)

- Injuries that transverse zones can also cause PTX

- Bleeding

- DO NOT PROBE wounds with active bleeding as may dislodge clot

- Vascular injuries are the most common cause of mortality (Kendall 1998)

- Application of direct pressure is often successful in controlling bleeding

- If possible, start access on the contralateral side to the injury

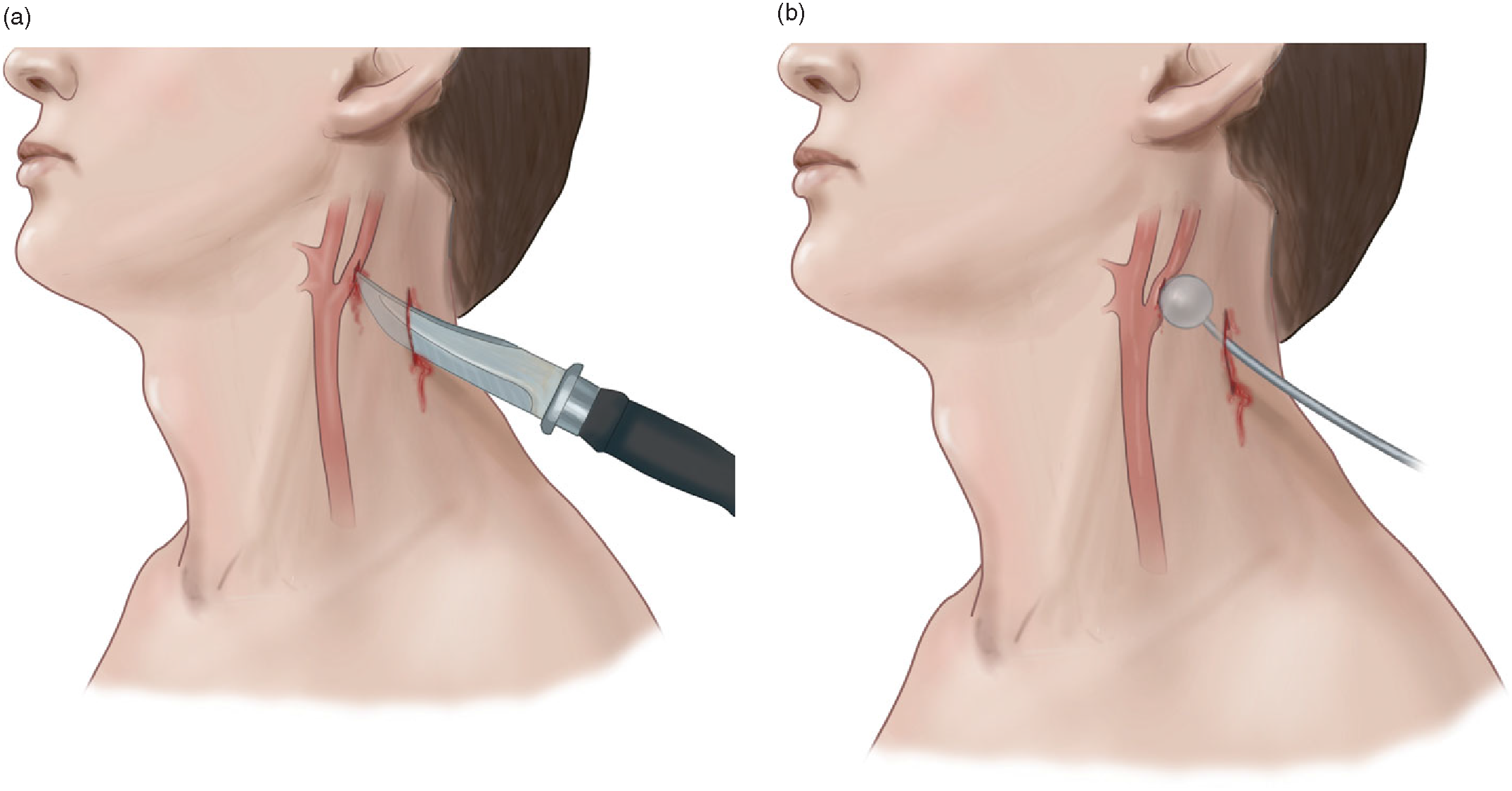

- If direct pressure cannot control bleeding, placement of a foley catheter and balloon inflation may be successful in tamponade of bleeding as a temporizing measure (Navsaria 2006)

- Airway

Balloon Tamponade of Vascular Injury

- Specific Injuries

- Pharyngoesophogeal Injuries

- Signs/Symptoms

- No pathognomic signs/symptoms

- Soft signs: hematemesis, dysphagia, subcutaneous emphysema, hoarseness, cough

- Diagnostics

- Plain X-rays (Thoma 2008, Bryant 2007)

- May suggest perforation but are not sensitive (cannot rule out injury)

- Findings: pneumomediastinum, retropharyngeal air

- Contrast esophogram with poor sensitivity for injury (Asensio 1997)

- Gastrograffin and barium studies may be performed. Gastrograffin may be safer as it is water-soluble and leakage is less likely to cause a chemical mediastinitis

- Flexible endoscopy offers direct visualization and is consider to be the most sensitive for ruling out injuries. It is often used in combination with contrast enhanced studies

- Plain X-rays (Thoma 2008, Bryant 2007)

- Because esophageal injuries are difficult to diagnose and there is no ideal approach, observation with reassessment is often necessary

- Treatment

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics (with coverage of anaerboes)

- Nasogastric tube typically placed under endoscopic guidance to avoid further injury

- Signs/Symptoms

- Laryngotracheal Injuries

- Signs/symptoms

- Hard signs: Bubbling or air leakage from a neck wound, massive subcutaneous air

- Soft signs: dyspnea, dysphonia, stridor, hemoptysis, subcutaneous emphysema, laryngeal crepitus

- Diagnostics

- Plain X-rays: extraluminal air, foreign bodies, fracture of cartilaginous structures (i.e. larynx), edema

- CT scan

- Need to obtain thin slices (1-mm) and multiplanar reconstructions

- Do not rely solely on the cervical spine CT

- Laryngoscopy and nasopharyngoscopy with flexible endoscopes are necessary for evaluating internal injuries

- Signs/symptoms

- Vascular Injuries

- Signs/symptoms

- Hard signs: active hemorrhage, expanding or pulsatile hematoma, hematemesis

- Soft signs: Venous oozing, nonpulsatile, nonexpanding hematomas, minor hemoptysis

- Diagnostics

- CT Angiogram (CTA)

- Most commonly used imaging modality for vascular trauma

- Performance characteristics (Rosen’s 2010)

- Sensitivity 90-100%

- Specificity 99-100%

- Should be obtained in all patients with soft signs of vascular trauma and selectively in patients without hard or soft signs

- Conventional angiogram

- Previously considered the gold standard diagnostic modality for vascular injuries

- Downsides: time consuming, large contrast load

- Continues to be used in patients with negative CTA but high suspicion of injury

- CT Angiogram (CTA)

- Signs/symptoms

- Pharyngoesophogeal Injuries

Disposition

- Patients with hard signs of aerodigestive or neurovascular injuries will require emergency surgery

- Patients with soft signs of aerodigestive or neurovascular injuries will move on to further imaging and should be admitted to a trauma surgery service (or transferred to one)

- Patients with neither hard nor soft signs of aerodigestive or neurovascular injuries may have imaging or, may simply be observed depending on local protocols

Take Home Points

- Penetrating injuries to the neck can damage a host of structures. Understanding the zones of the neck and the structures within them can help predict injuries

- If the platysma is violated, it should be assumed that deep structures have been injured until proven otherwise

- Early airway management is crucial as injuries can lead to dynamic airway obstruction. Always be prepared for a surgical airway

- The presence of any hard signs of aerodigestive/neurovascular injuries (expanding/pulsatile hematoma, active brisk bleeding, hemorrhagic shock, massive subcutaneous emphysema, air bubbling through the wound, neurologic deficit) or violoation of platysma, mandates an immediate OR trip. Do not delay the patient getting to the OR for additional studies

- Attempt to control vascular injuries with direct pressure and consider balloon tamponade with a foley catheter

References

Evans C et al. Management of Major Vascular Injuries: Neck, Extremities and Other Things that Bleed. Emerg Med Clin N Am 2018; 36: 181-202. PMID: 29132576

Sperry JL et al. Western Trauma Association Critical Decisions in Trauma: Penetrating Neck Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013; 75(6): 936-41. PMID: 24256663 [OPEN ACCESS]

Newton K, Claudius I. Neck, in Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al (eds): Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, ed 8. St. Louis, Mosby, Inc., 2010, (Ch) 44: p 421-432

Kendall JL, Anglin D, Demetriades D: Penetrating neck trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1998; 16(1): 85-105. PMID: 9496316

Haut ER et al. Spine immobilization in penetrating trauma: More harm than good? J Trauma. 2010; 68(1): 115–121. PMID: 20065766

Vanderlan WB et al. Increased risk of death with cervical spine immobilisation in penetrating cervical trauma. Injury. 2009; 40(8): 880–883. PMID: 19524236

Stuke LE et al. Prehospital spine immobilization for penetrating trauma: Review and recommendations from the Prehospital Trauma Life Support Executive Committee. J Trauma. 2011; 71(3): 763–770. PMID: 21909006

Lustenberger T et al. Unstable cervical spine fracture after penetrating neck injury: A rare entity in an analysis of 1,069 patients. J Trauma. 2011; 70(4): 870–872. PMID: 20805776

Theodore N et al. Prehospital cervical spinal immobilization after trauma. Neurosurgery 2013; 72, Suppl. 2: 22–34. PMID: 23417176

Thoma M et al. Analysis of 203 patients with penetrating neck injuries. World J Surg 2008; 32(12):2716-2723. PMID: 18931870

Bryant AS, Cerfolio RJ. Esophageal trauma. Thorac Surg Clin 2007; 17(1): 63-72. PMID: 17650698

Asensio JA, et al. Penetrating esophageal injuries: Time interval of safety for preoperative evaluation—how long is safe? J Trauma 1997; 43(2): 319-24. PMID: 9291379

Navsaria P et al. Foley catheter balloon tamponade for life-threatening hemorrhage in penetrating neck trauma. World J Sure 2006; 30(7): 1265-8. PMID: 16830215