Pharmacology

- Target GABAA receptor, a ligand-gated chloride channel

- Increases the frequency of channel opening (no effect in absence of GABA)

- Results in hyperpolarization of cell

- Common uses: seizures, psychomotor agitation, sedative-hypnotic withdrawal

Table 1: Commonly used benzodiazepines with their respective onset and duration of action of sedation (single dose) (Adapted from Hoffman et al 2015)

| Midazolam

(Versed) Quick on/quick off |

Diazepam

(Valium) Quick on/medium off |

Lorazepam

(Ativan) Medium on/long off |

|

| IM | 5-10 mg

Onset 5-15 min Duration 1-2 hr |

2-4 mg

Onset 30-45 min |

|

| IV | 2-5 mg*

Onset 1-3 min Peak effect 5 min Duration 30-80 min |

5-10 mg

Onset 1 min Peak effect 3 min Duration 1-2 hr |

2-4 mg

Onset 5-10 min Peak effect 30 min Duration 2-6 hr |

*Administer over at least 1 minute to avoid apnea

Pharmacokinetics

- Onset and peak effect for sedative vs anticonvulsant activity are different among single drugs

- IV preferred over IM for complete, reliable and immediate absorption

- IM lorazepam and midazolam also have good absorptive profiles

- IM diazepam is not advised due to erratic and unpredictable absorption

Medication Effects

- Effective for agitation or seizure with unknown underlying etiology

- Broad spectrum sedative agent with few drug-drug interactions, specifically no effect on QTC prolongation

- Relative safety in patients with hepatic and renal dysfunction

- Diazepam with active metabolites hepatically metabolized

- (consider alternate agent only in severe liver disease)

- Although concurrent alcohol intoxication is not a contraindication, synergistic effects on CNS and ventilation may lead to respiratory compromise. Consider using a lower starting dose.

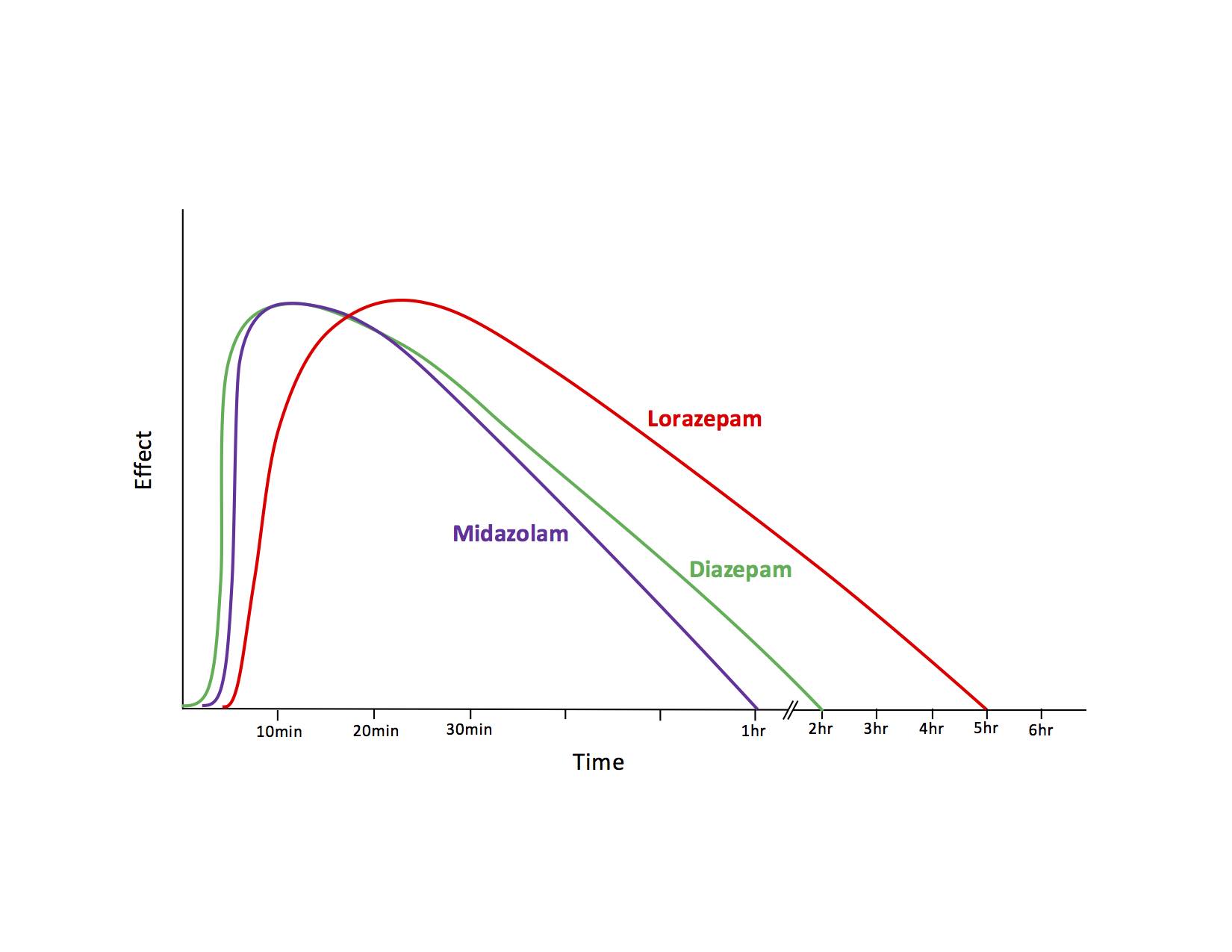

Sedative Effects

- Intravenous administration preferred for rapid and reliable absorption and effect

- Midazolam has a rapid onset, short time to peak effect, and a short duration of effect

- Diazepam may be useful when a longer duration of action is desirable [active metabolites]

- Lorazepam requires a longer time to reach peak effect than either midazolam or diazepam and may lead to stacking doses

- When IV access is not available, IM midazolam (Versed) is preferred

- Midazolam preferred for elderly; half-dose to avoid prolonged sedation

Graph 1. Time to effect and duration of action of IV benzodiazepines for sedation (single dose)

Anticonvulsant Effects

- Administer early and in appropriate doses

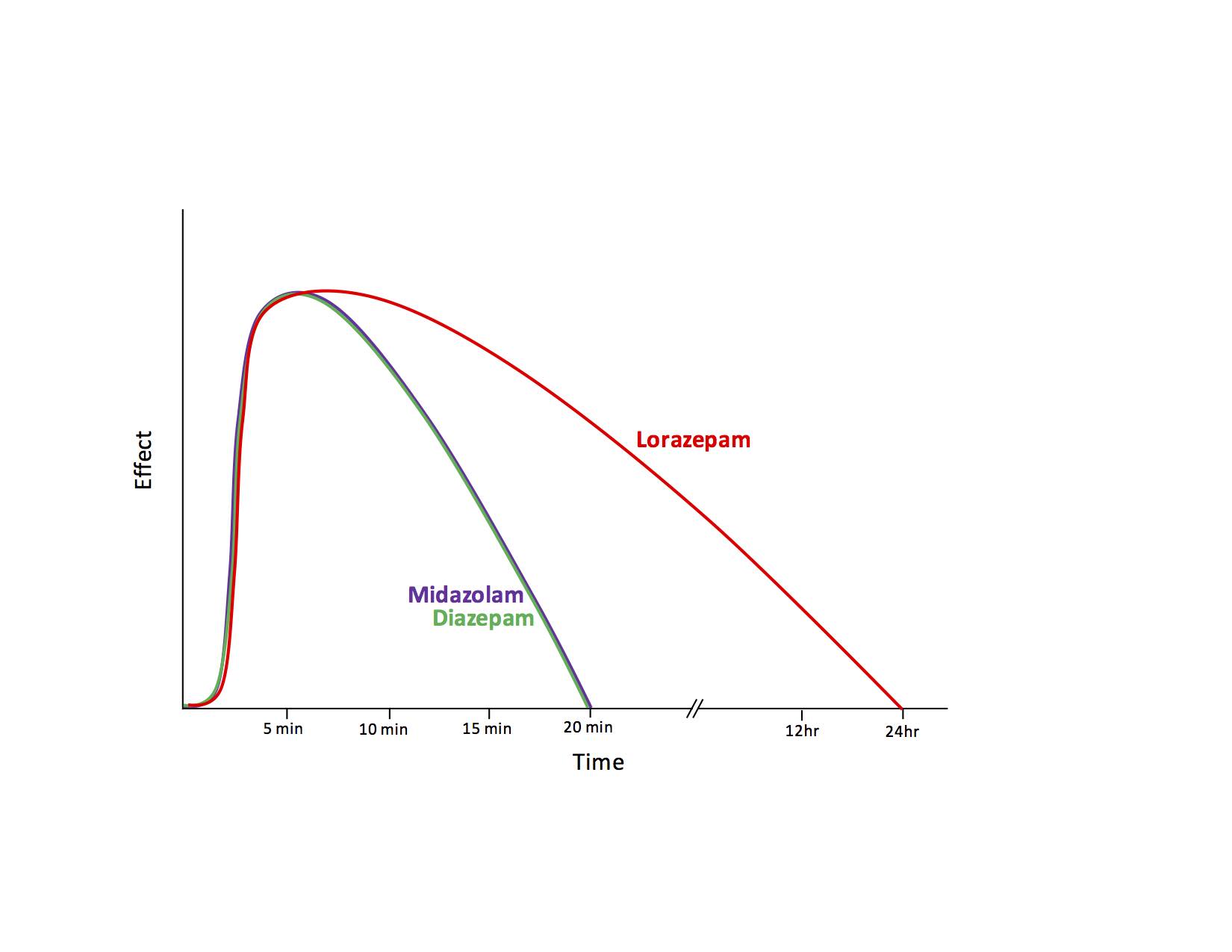

- All benzodiazepines distribute into the CNS (lipophilic) and are anticonvulsants

- Duration dependent on redistribution to peripheral tissue sites

- While diazepam has slightly more rapid onset of action, it is rapidly redistributed to peripheral fat stores

- Because of its lipophilicity, clinical effectiveness of diazepam is limited to only 20-30 minutes (Manno 2003)

- Potential for high relapse rate given the short duration of action seen with diazepam and midazolam

- IV Lorazepam (Ativan) generally preferred agent given extended duration of effect (Treiman 1998)

- First dose 0.1 mg/kg (maximum 4mg), repeat PRN one or two times

- Early treatment, often in the pre-hospital setting, lowers the risk of prolonged seizures (Alldredge 2001)

- Rectal or IM administration may be necessary when IV access is unavailable during emergency transport

Graph 2. Time to effect and duration of action of IV benzodiazepines for anticonvulsant properties

Status Epilepticus

- The definition of status epilepticus has been reduced from 30 min of persistent seizures to 5 min, as longer seizures are more difficult to control

- The scope of status epilepticus will not be discussed here but the mainstays of therapy include immediately terminating seizures, identifying underlying cause (i.e. hypoglycemia, toxic, metabolic, trauma) and general supportive care/airway management

- Benzodiazepines are the first line agent to treat status epilepticus, but other pharmacologic interventions may include propofol, fosphenytoin or phenytoin (but not for drug induced seizures), valproic acid, phenobarbital, pentobarbital and even high dose pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) for INH/hydrazine exposures.

Special Populations

- Elderly

- Midazolam (Versed) is preferred for overall shorter duration of action. Start with half-dose to avoid prolonged sedation.

- Older patients can be more sensitive to the sedative and respiratory depressant effects of benzodiazepines.

- Pediatric

- Rectal, buccal, and intranasal formulations of benzodiazepines are frequently used in outpatient setting for abortive therapy.

- The RAMPART study (Silbergleit 2011) demonstrated IM midazolam was non-inferior to IV lorazepam (2-4 mg) in the pre-hospital setting. However, in the emergency department, IV administration is still typically preferred whenever possible.

- IV Lorazepam and diazepam are equivalent in both efficacy and safety outcomes in the pediatric population (Chamberlain 2014).

Adverse Effects

- Most common adverse effect is CNS depression

- Respiratory depression

- Extra caution is advised with elderly populations as described above

- Paradoxical reactions may be seen with increased agitation following administration. This is thought to be secondary to disinhibition and may respond to larger doses.

- IV administration may produce mild reduction in heart rate and both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, but direct myocardial effects are rare.

Monitoring After Administration

- All patients should receive continuous cardiac and respiratory monitoring, including pulse oximetry

- End-tidal CO2 (EtCO2) monitoring should be used if available but may not be entirely reliable. Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis is indicated if such monitoring if not available or the EtCO2 readings are not consistent with the clinical findings.

- Supplemental oxygen may mask objective signs of hypoventilation. It should only be used if the patient is continuously clinically monitored.

Take Home Points

- Duration of each dose dependent on underlying etiology of patient’s presentation, e.g. metabolic, epilepsy, trauma, toxicologic

- Underlying chronic use of benzodiazepines, sedative-hypnotics, or CNS depressants (whether prescribed or illicit) may demonstrate variable response and may require higher cumulative doses

- Benzodiazepines are excellent broad spectrum sedative agents for agitation and seizures of unknown etiology

- Sedative/anticonvulsant with few drug-drug interactions

- Special attention should be paid to airway positioning as oropharynx tissue relaxation after benzodiazepine administration can often lead to airway obstruction

- All patients should receive continuous cardiac and respiratory monitoring, including pulse oximetry

- End-tidal CO2 (EtCO2) monitoring should be used if available but may not be entirely reliable. Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis is indicated if such monitoring if not available or the EtCO2 readings are not consistent with the clinical findings.

- Supplemental oxygen may mask objective signs of hypoventilation. It should only be used if the patient is continuously clinically monitored.

References

Alldredge BK, Gelb AM, Isaacs SM, et al. A comparison of lorazepam, diazepam, and placebo for the treatment of out-of-hospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:631-637. PMID: 11547716

Claassen J, Hirsch LJ, Emerson RG, Mayer SA. Treatment of refractory status epilepticus with pentobarbital, propofol, or midazolam: a systematic review. Epilepsia 2002; 43: 146-153. PMID: 11903460

Chamberlain JM, Okada P, Holsti M, et al; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN). Lorazepam vs diazepam for pediatric status epilepticus: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014; 311(16):1652-60. PMID: 24756515

Hoffman RS, Nelson LS, Howland MA. Antidotes in depth: Benzodiazepines. In: Hoffman RS, Howland MA, Lewin NA, et al. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies, 10th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Professional, 2015: 1069-1075.

Manno EM. New management strategies in the treatment of status epilepticus. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:508-518. PMID: 12683704

Silbergleit R, Lowenstein D, Durkalski V, et al; NETT Investigators. RAMPART (Rapid Anticonvulsant Medication Prior to Arrival Trial): A double-blind randomized clinical trial of the efficacy of IM midazolam versus IV lorazepam in the pre-hospital treatment of status epilepticus by paramedics. Epilepsia 2011; 52:45-47. PMID: 21967361

Sinha S, Naritoku DK: Intravenous valproate is well tolerated in unstable patients with status epilepticus. Neurology 2000;55:722-724. PMID: 10980746

Treiman DM, Meyers PD, Walton NY, et al. Veterans Affairs Status Epilepticus Cooperative Study Group. A comparison of four treatments for generalized status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:792-798. PMID: 9738086