Background

- A surgical abdomen in the neonate is a rare event, but is associated with high morbidity and mortality.

- Intestinal obstruction can quickly lead to severe dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, sepsis and irreversible intestinal ischemia.

- Early recognition and intervention are crucial to maintain intestinal perfusion and prevent the serious sequelae of short gut syndrome.

Clinical Presentation

- In almost every case of intestinal obstruction the neonate will present with vomiting.

- Vomiting in the neonatal period is a common complaint and often associated with benign etiologies such as gastroesophageal reflux.

- Vomiting in this period should always raise concern of a serious underlying disease.

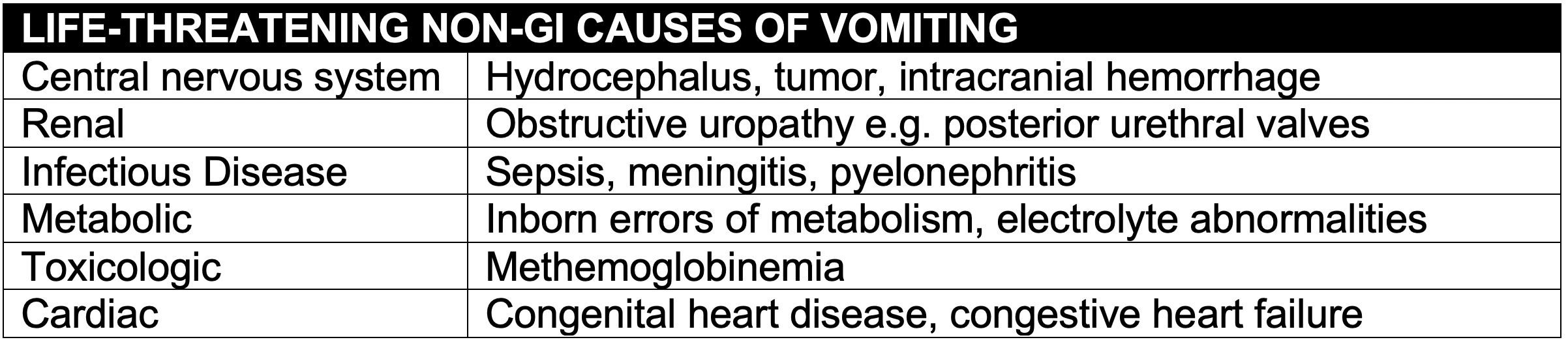

- The differential diagnosis of vomiting is extensive. Though gastrointestinal obstruction should be considered, it is helpful to think about vomiting etiologies in other systems first

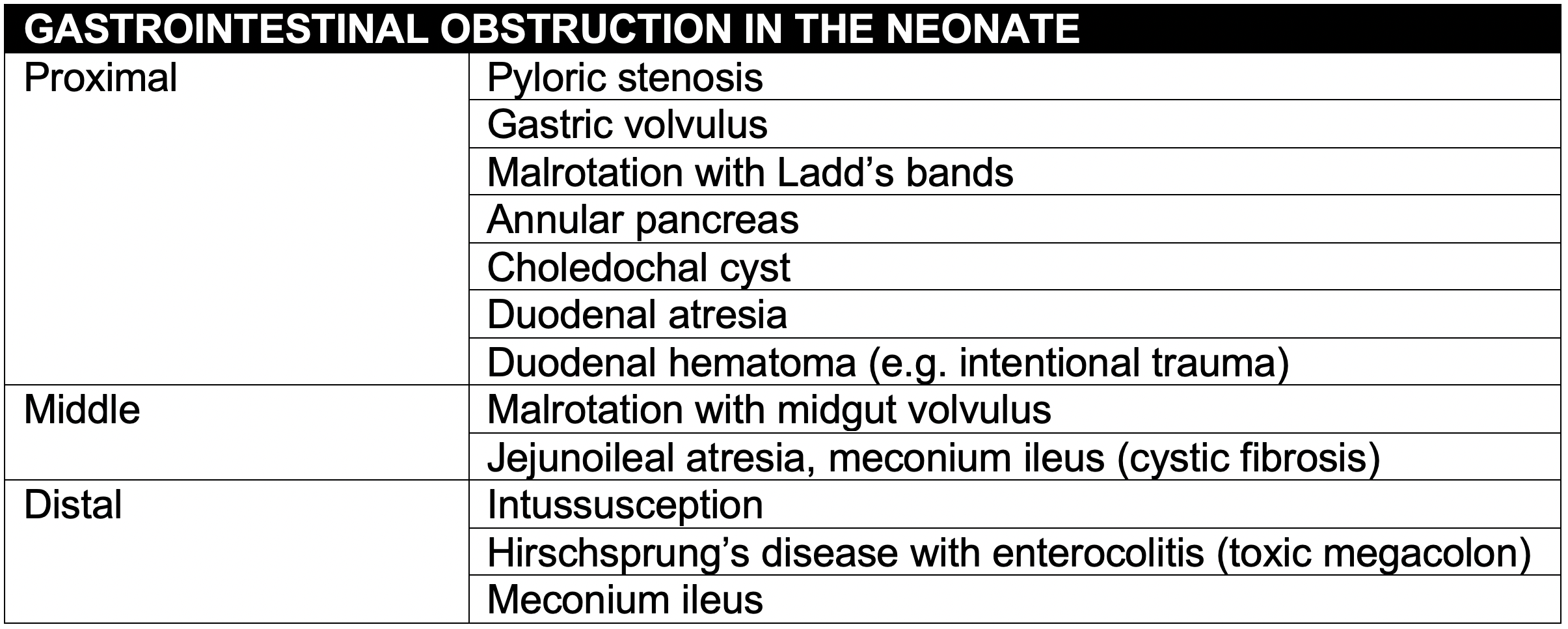

- The age of the patient and presenting symptoms may help in to narrow the differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal causes of vomiting.

- Neonates are more likely to have a congenital abnormality.

- Older infants are more likely to have an acquired etiology or a late complication of a congenital abnormality.

- Bilious vomiting and abdominal distension suggest a level of obstruction below the sphincter of Oddi (e.g. malrotation with midgut volvulus).

- In contrast, non-bilious vomiting and gastric distention may indicate a more proximal cause of obstruction (e.g. pyloric stenosis).

Non-Emergency Causes of Emesis

- Although this post focuses on neonatal intestinal emergencies, we will quickly touch on causes of emesis that do not represent surgical emergencies

- Pyloric stenosis: characterized by projectile, non-bilious emesis in patients at least 3 weeks of age, caused by hypertrophy of the pylorus. Although this can be characterized by electrolyte abnormalities, it is typically caught before these develop

- Gastroesophageal reflux (GER): a physiologic condition which is characterized by non-forceful emesis and is due to poor tone in the lower esophageal sphincter

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): patients with emesis as above but also with fussiness, feeding aversion, and in some cases bradycardia and/or cyanotic episodes

- Milk protein allergy: non-IgE-mediated intolerance characterized by vomiting, diarrhea, and failure to thrive, owing to inability to break down milk proteins in breast milk or formula

- Gastroenteritis: like older children, neonates may have infectious gastroenteritis

- Intracranial hypertension: neonates with increased ICP from causes such as space-occupying lesions and non-accidental trauma may have vomiting and are likely to have a bulging fontanelle

- Inborn errors of metabolism: although rare, these disorders can cause emesis, and they should be considered in an ill-appearing neonate

Necrotizing enterocolitis

Introduction

- Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) causes significant disease in premature and very low birthweight infants but can occur in healthy term infants as well

- Term infants with decreased intestinal perfusion caused by conditions such as cardiac or gastrointestinal diseases, perinatal hypoxia, sepsis, and intrauterine growth restriction may be at increased risk of NEC

- It most commonly occurs during the first two weeks of life

Clinical Manifestations

- NEC may be characterized by abdominal distention, emesis, and bloody stools

- Patients may also present with lethargy and cardiopulmonary collapse

Diagnosis

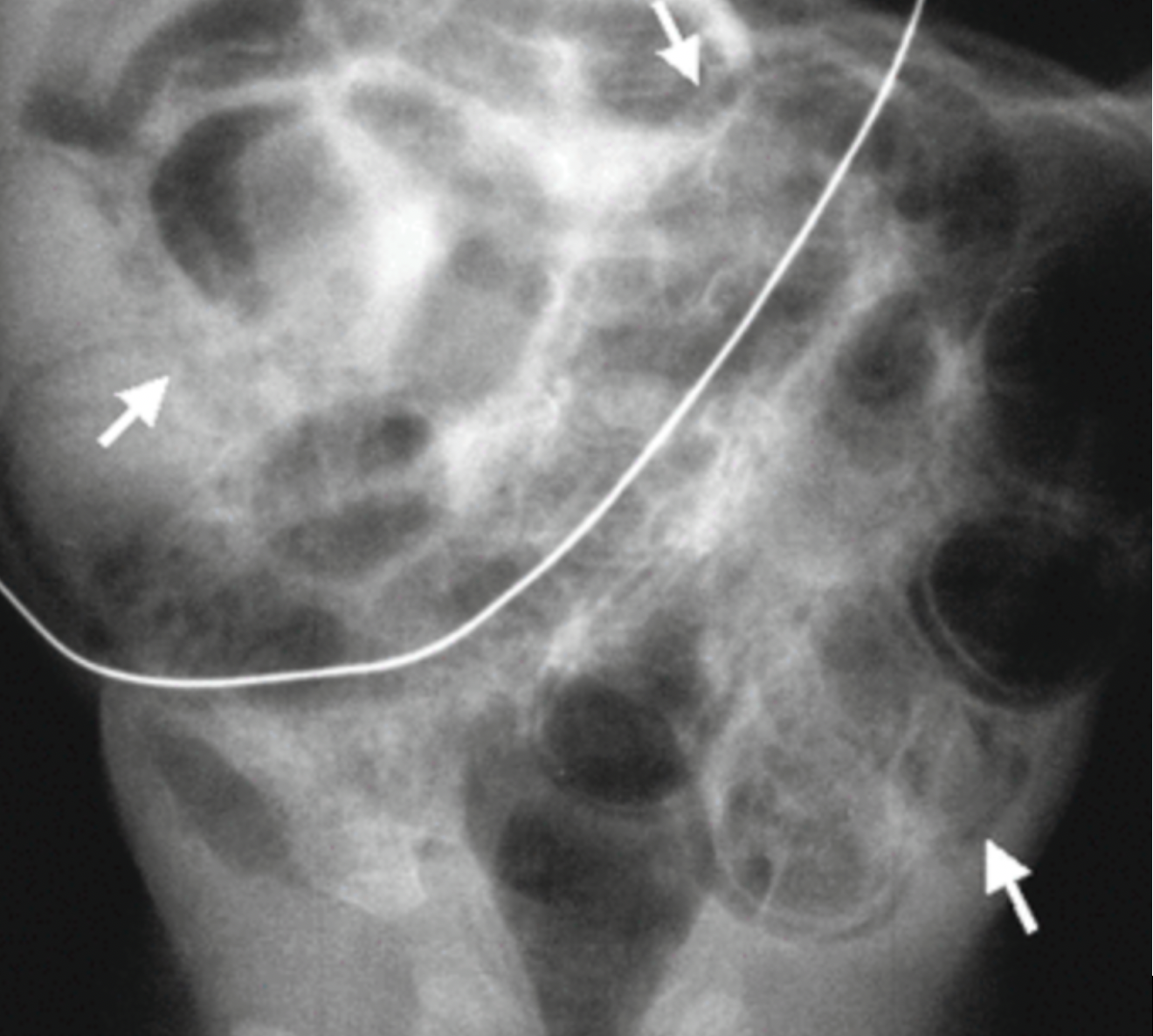

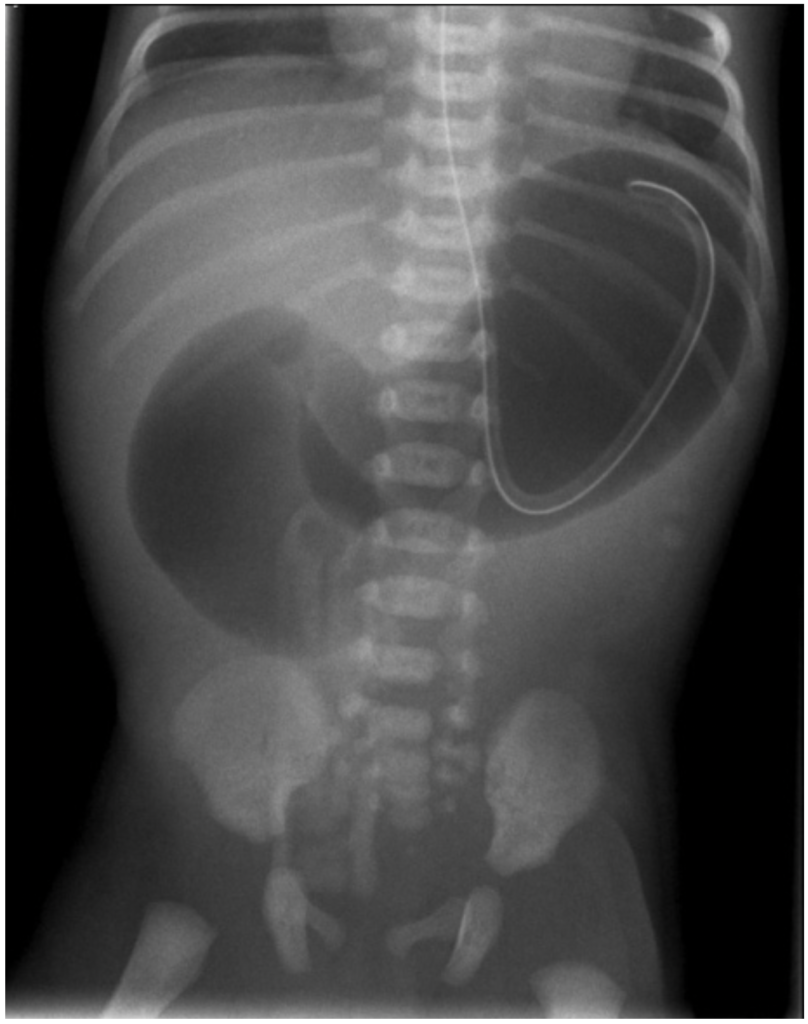

- Diagnosis is made by abdominal radiographs, which can show nonspecific findings including distension and thickened bowel wall (Figure 1)

- Pneumatosis intestinalis is pathognomonic for NEC, and is characterized by bowel wall lucencies (Figure 2)

- Bowel perforation may lead to pneumoperitoneum, and radiography may also show portal venous gas

Management

- Management includes resuscitation, supportive care with bowel rest and gastric decompression, and antibiotics

- Bacteremia may be seen in up to 30 percent of neonates with NEC, and antibiotics should be broad-spectrum and cover intestinal flora

- Surgical management is necessary for patients with bowel necrosis, and may include primary peritoneal drainage and/or laparotomy

Figure 1: Nonspecific intestinal distention

Figure 2: Pneumatosis intestinalis

Hirschsprung-Associated Enterocolitis (HAEC)

Introduction

- Hirschsprung disease (HD) is most commonly diagnosed in neonates; however, it can be missed, especially if aganglionosis is incomplete

- HD is associated with Down syndrome and other chromosomal and genetic abnormalities

Clinical Manifestations

- Typical symptoms of Hirschsprung disease in the absence of enterocolitis include bilious emesis, abdominal distension, and failure to pass meconium

- Normal full-term infants pass meconium by 48 hours of life, and parents should be asked about perinatal bowel movements

- Patients with HAEC will have some combination of fever, abdominal distention, emesis, and explosive diarrhea, and are likely to present in extremis

- Toxic megacolon is characterized by significant colonic dilation with septicemia

- Patients with HD may also have volvulus, usually in the sigmoid colon, which presents with abdominal distention and emesis

Diagnosis

- Abdominal radiographs will show distended loops of bowel and often air-fluid levels

- “Cutoff sign” may be present and is characterized by an abrupt cutoff of air in the rectosigmoid colon (figure 3)

- Contrast enema poses the risk of intestinal perforation and should be avoided

Management

- Management of HAEC and toxic megacolon includes resuscitation with fluids, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and gastric decompression where indicated

- Patients who have not yet undergone colonic resection for HD generally require surgical repair, whereas postoperative patients with HAEC may be treated with antibiotics and supportive care

Figure 3: HAEC “Cutoff Sign”

Malrotation

Introduction

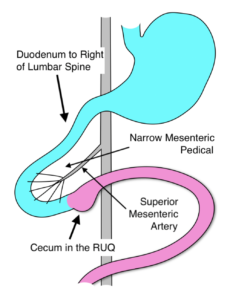

- During embryonic life, the colon and small bowel grow rapidly rotating 270 degrees in a counter-clockwise direction, with the cecum passing anterior to the superior mesenteric artery and coming to rest in the right lower quadrant.

- In malrotation, the rotation ceases after 90 degrees. The duodenum and ascending colon are juxtaposed around the superior mesenteric vessels, with the entire midgut suspended from a narrow mesenteric pedicle.

- Malrotation is not, in itself, a problem. However, two distinct clinical situations may complicate malrotation. The most severe is midgut volvulus. The other is duodenal obstruction due to Ladd’s bands.

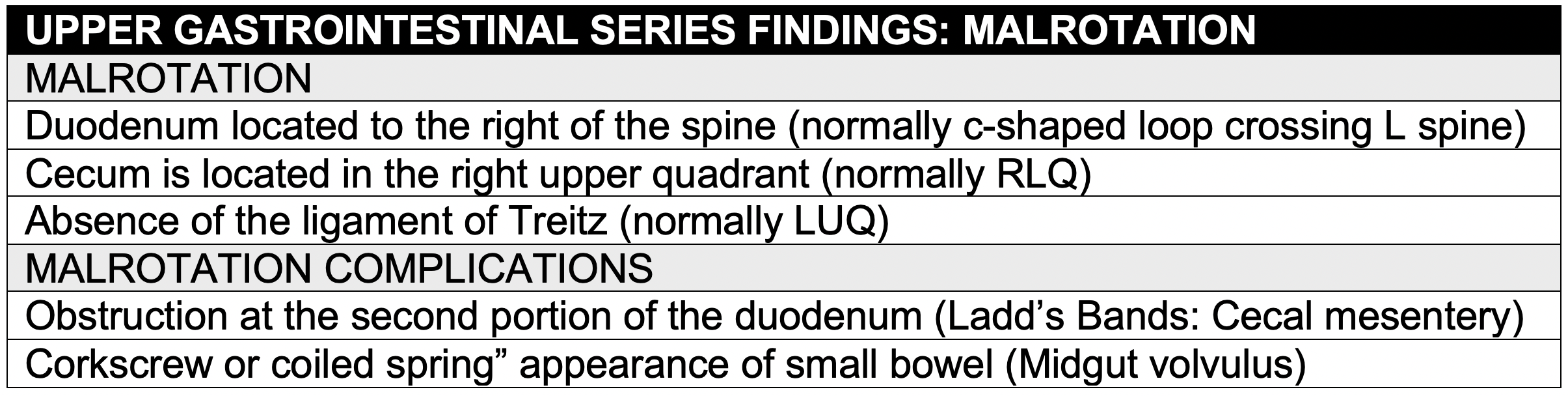

Imaging

- Malrotation is diagnosed with an upper GI series. Ultrasound can be diagnostic when performed by an experienced pediatric radiologist.

Midgut Volvulus

Introduction

- The midgut can twist around its narrow mesenteric pedicle resulting in a midgut volvulus.

- Progressive bowel strangulation results in an ischemic loss of extensive bowel.

- Most patients with malrotation develop midgut volvulus within the first weeks of life.

- Bilious vomiting is often the initial symptom.

- The clinical course is rapid progression from midgut ischemia to necrosis with perforation leading to hemodynamic instability, sepsis and metabolic acidosis.

Imaging

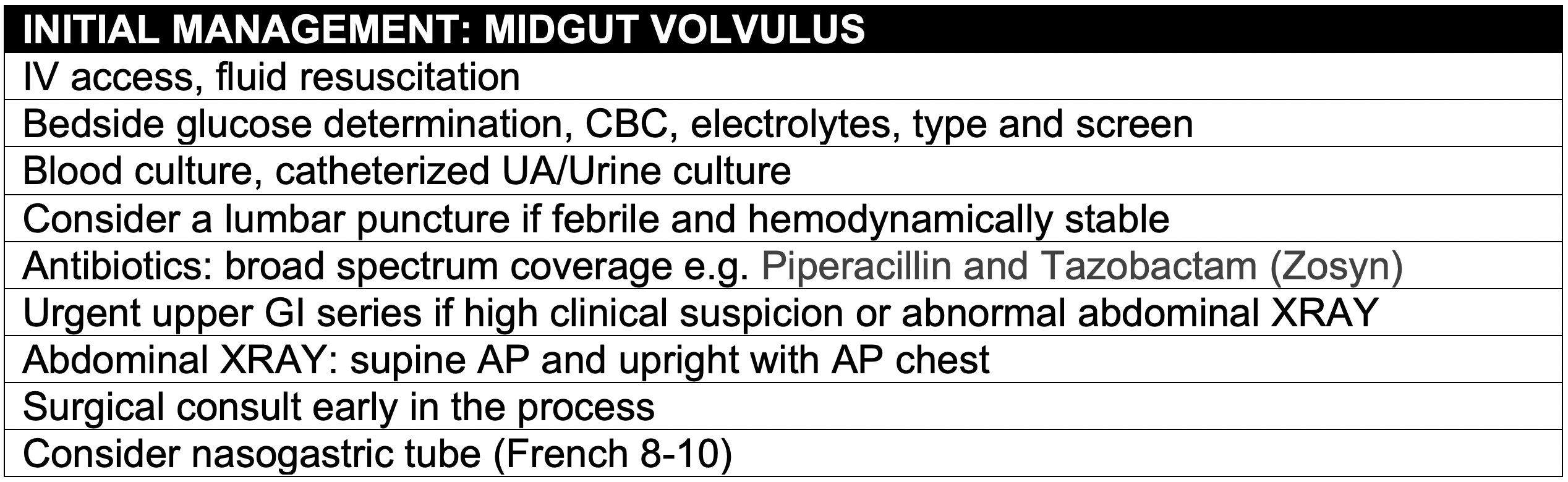

- Depending on the progression of the strangulation an abdominal X-ray will show evidence of small bowel obstruction or lack of any gas in the abdomen. Free air may be seen due to ischemic bowel perforation.

- An upper GI series will demonstrate a “cork screw” appearance of the small bowel.

- Emergent operative intervention to preserve bowel is essential.

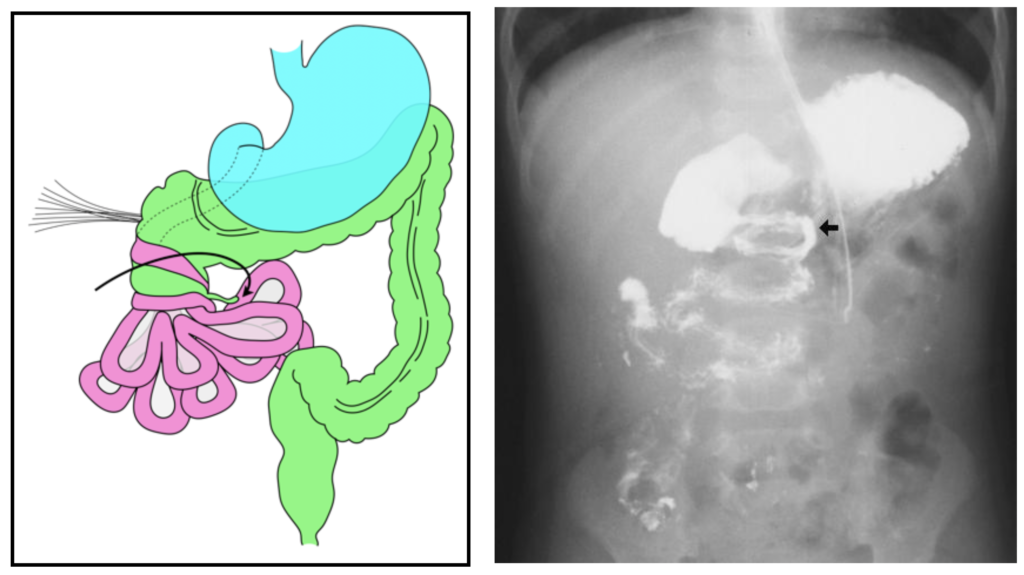

Management

Duodenal Obstruction due to Ladd’s Bands

- With normal rotation the cecum migrates to the right lower quadrant and the cecal mesentery attaches to the abdominal wall in that location.

- In malrotation, the cecum remains in the right upper quadrant.

- The cecal mesentery (Ladd’s Bands) crosses the duodenum to attach to the liver and can obstruct the mid duodenal.

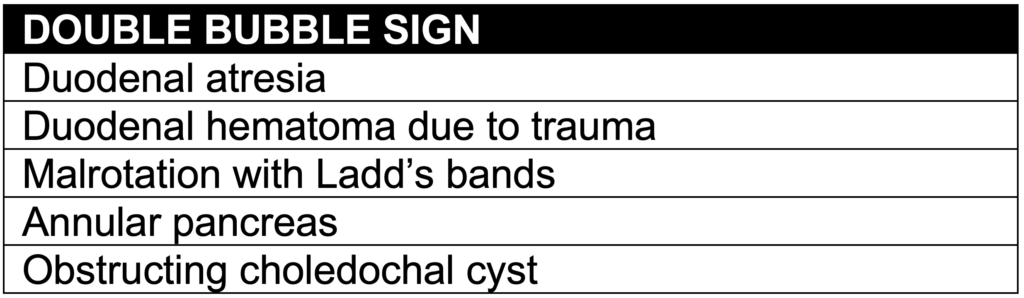

- Abdominal plain film shows a characteristic “double-bubble” sign, demonstrating gastric distention (proximal bubble) in the and the dilated proximal duodenum (distal bubble). The narrowing between the two bubbles is the pylorus and the duodenal obstruction occurs at the end of the distal bubble.

- Surgery is required but is not urgent.

References

Berrocal T., Parrón M., del Pozo G. (2016) Gastrointestinal Emergencies in the Neonate. In: Stafrace S., Blickman J. (eds) Radiological Imaging of the Digestive Tract in Infants and Children. Medical Radiology. Springer, Cham

Demehri, Farokh & Halaweish, Ihab & Coran, Arnold & Teitelbaum, Daniel. (2013). Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis: Pathogenesis, treatment and prevention. Pediatric surgery international. 29. 10.1007/s00383-013-3353-1.

Fonkalsrud E. Rotational anomalies and volvulus. In: Principles of Pediatric Surgery, O’Neill JA et al (Ed), Mosby, St. Louis 2003. p.477.

Gomiz, E.B., Ayats, A.T., Feliubadaló, C.D., Martinez, C.M., & Tarragó, A.C. (2015). Intestinal malrotation – volvulus: Imaging findings.

Nehra D, Goldstein AM. Intestinal malrotation: varied clinical presentation from infancy through adulthood. Surgery 2011; 149:386.