Definition:

- broad term for severe soft tissue infections with necrosis of the fascial and subcutaneous layers, possibly extending to the muscle, causing systemic toxicity and high mortality

- necrotizing soft tissue infections can be classified by:

- anatomic location with eponyms (Ludwig’s angina: submandibular fascial spaces; Fournier’s gangrene: perineal region to anterior abdominal wall)

- depth of infection (necrotizing adipositis, fasciitis, myositis)

- microbial cause (Types I, II, III, IV)

- necrotizing soft tissue infections can be classified by:

- can spread as fast as 1 inch per hour!

Epidemiology:

- anywhere from 0.3-15 cases per 100,000 people depending on region

- risk factors: diabetes, ulcers, hemorrhoids, gynecologic/colonic/urologic surgeries, advanced age, alcoholism, peripheral vascular disease, renal disease, heart disease, immunosuppression, IV drug abuse

- 80% of cases arise from direct extension from skin lesion

- mortality has decreased from 25% to 10% over the past 20 years in the US

Pathophysiology

- different types:

- type I: polymicrobial (55-75% of all necrotizing soft tissue infections)

- often associated with gas forming microbes

- majority of cases are polymicrobial including gram-positive cocci, gram-negative rods, and anaerobes

- associated with patients with preexisting comorbidities as above

- type I: polymicrobial (55-75% of all necrotizing soft tissue infections)

- type II: monomicrobial (20-30%)

- seen often in patients who do not have any chronic comorbidities

- group A Streptococcus most common agent – called “Flesh-Eating Bacteria” in media

- Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) also common but appears to be less virulent than Group A streptococcus

- clostridial infections

- often associated with traumatic injury (~70% of gas gangrene); traumatic injury leads to ischemic hypoxic environment, where anaerobic organisms proliferate

- 80% of these infections due to clostridium perfringes

- type III: no consensus definition

- other pathogens including Vibrio Vulnificus (found in seawater) and Aeromonas hydrophila

- type IV: fungal infections typically occurring in immunocompromised patients

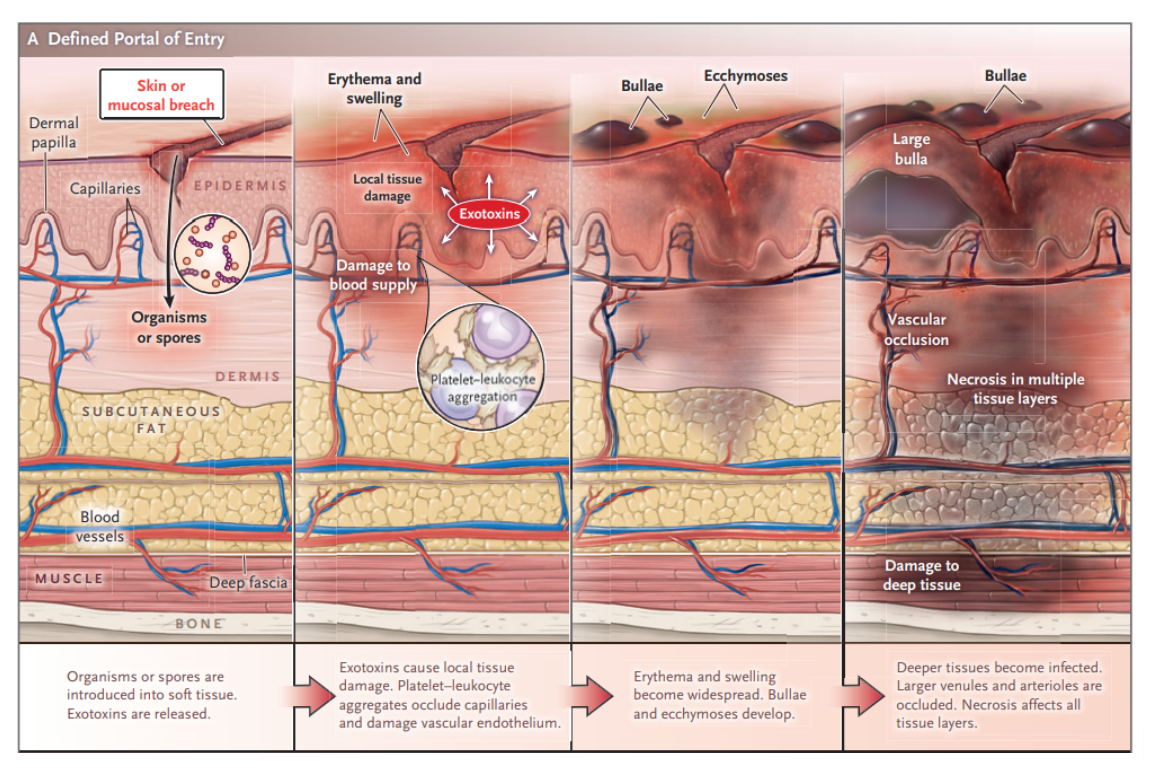

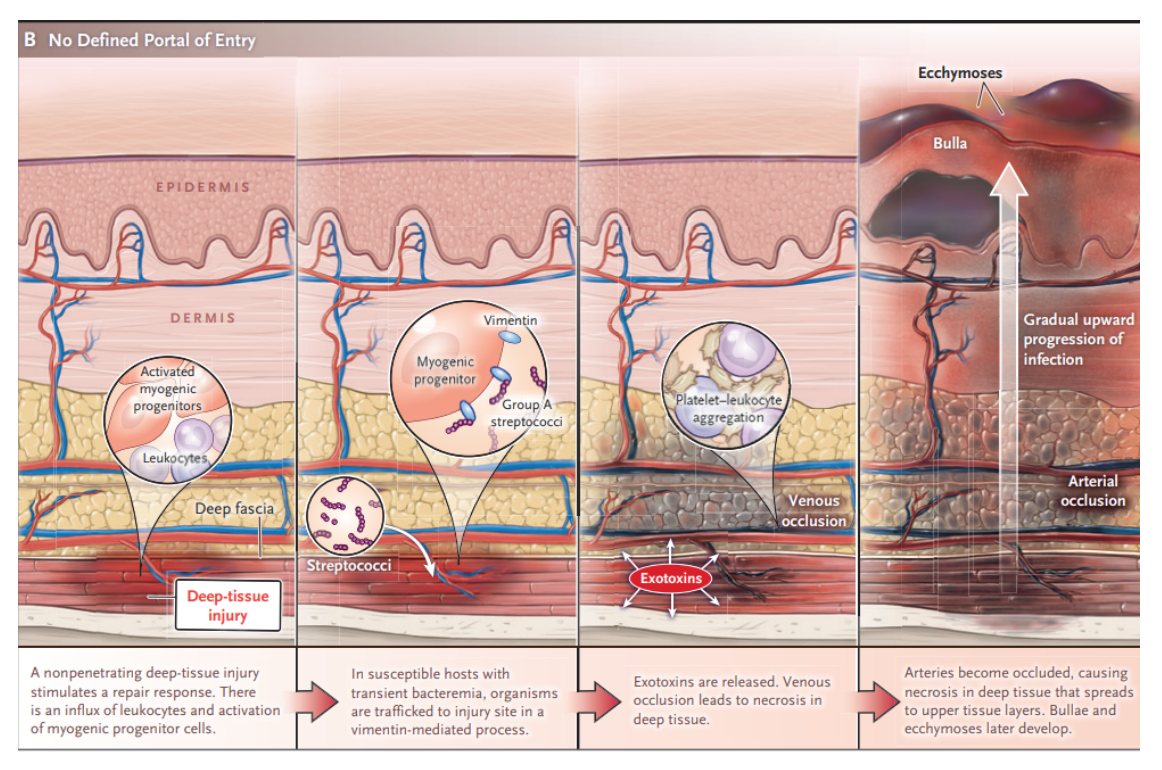

- bacteria spreads directly from perforated viscus (colon, rectum, anus), originates from compromised tissue (traumatic wound, IV injection, surgical incision, insect bite, abscess, ulcer), or develops spontaneously then proliferates leading to vasculitis and thrombophlebitis

- ischemic tissue then promotes liquefaction necrosis and bacterial growth

- bacterial exotoxins cause further ischemia, necrosis, and systemic toxicity

- in polymicrobial infections, there may be a symbiotic relationship between different bacteria

Presentation:

- symptoms:

- initial symptoms can be vague: fever, body aches, nausea, diarrhea, anxiety

- there may be diffuse, localized pain in an extremity with a possible appearance of simple cellulitis (warmth, erythema, tenderness)

- specifically pain out of proportion to exam is a concerning finding

- crepitus can be indicative of gas-forming bacteria

- lack of crepitus does NOT rule out diagnosis: present in only ~20% of patients in 2 studies

- findings helpful to differentiate necrotizing soft tissue infection from normal cellulitis:

- pain out of proportion to exam

- hypotension

- skin necrosis

- hemorrhagic bullae

- crepitus

- altered mental status

- tachycardia out of proportion to fever

- between 24-72 hours, skin changes include:

- inflammation, duskiness and purplish hue, possible bullae (found more commonly in Group A strep)

- late findings:

- anesthesia and insensate areas as superficial nerves become infarcted

- bacteremia leading to systemic symptoms including fevers, chills, tachycardia, hypotension, disseminated intravascular coagulation

- important pitfalls of diagnosis:

- absence of fever

- patient has not mounted systemic response as infection is localized to extremity

- patient used analgesics/antipyretics at home

- absence of observable cutaneous manifestations

- infection may originate from deep compartments and arise to superficial skin as a late finding

- cellulitis may be subtle because thrombosis of a large number of capillary beds is necessary before skin changes occur

- relying on imaging modalities to rule out diagnosis

- necrotizing soft tissue infection is a clinical diagnosis

- absence of fever

Diagnosis

- pillar of diagnosis is the clinical presentation, history and physical

Gold Standard:

- direct visualization in the operating room exploring soft tissue for necrosis of fascia and muscular layers of soft tissue

- classic “dishwater” fluid secondary to destruction of layers

- not feasible to use this gold standard on every patient

LRINEC score:

- retrospective observational study of 89 patients looking at laboratory differences between patients with confirmed necrotizing fasciitis and those with severe cellulitis or abscess (2004)

- laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis (LRINEC)

- Point values (0-4) were assigned to different ranges for CRP, WBC, hemoglobin, sodium, creatinine, glucose

- in the original paper, a score of 6 or more points had a positive predictive value of 92% and negative predictive value of 96%

- however, LRINEC yielded lower sensitivity and specificity in further studies in a 2019 meta-analysis in Annals of Surgery (sensitivity of 68.2% and specificity of 84.8%)

- LRINEC can be useful to help support argument for ruling in the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis in an otherwise healthy patient, but should not be used to rule out the diagnosis

- lab tests are largely all non-specific indicators of inflammation that can be associated with any inflammatory/infectious process

Finger Test:

- controversial procedure that has not been formally studied

- procedure involves injecting local anesthetic near area of concern, creating a 2 cm laceration down to fascial layer, then observing for abnormal or lack of blood flow and presence of dishwater-colored fluid

- clinician next inserts a gloved, sterile finger to test for fascial continuity and normal tissue firmness

- if tissue dissects with minimal resistance encountered, concern for necrotizing soft tissue infection

- if you are performing the finger test, keep in mind that it is user-dependent; recommended to have a surgical consult at the bedside for a second opinion

Imaging:

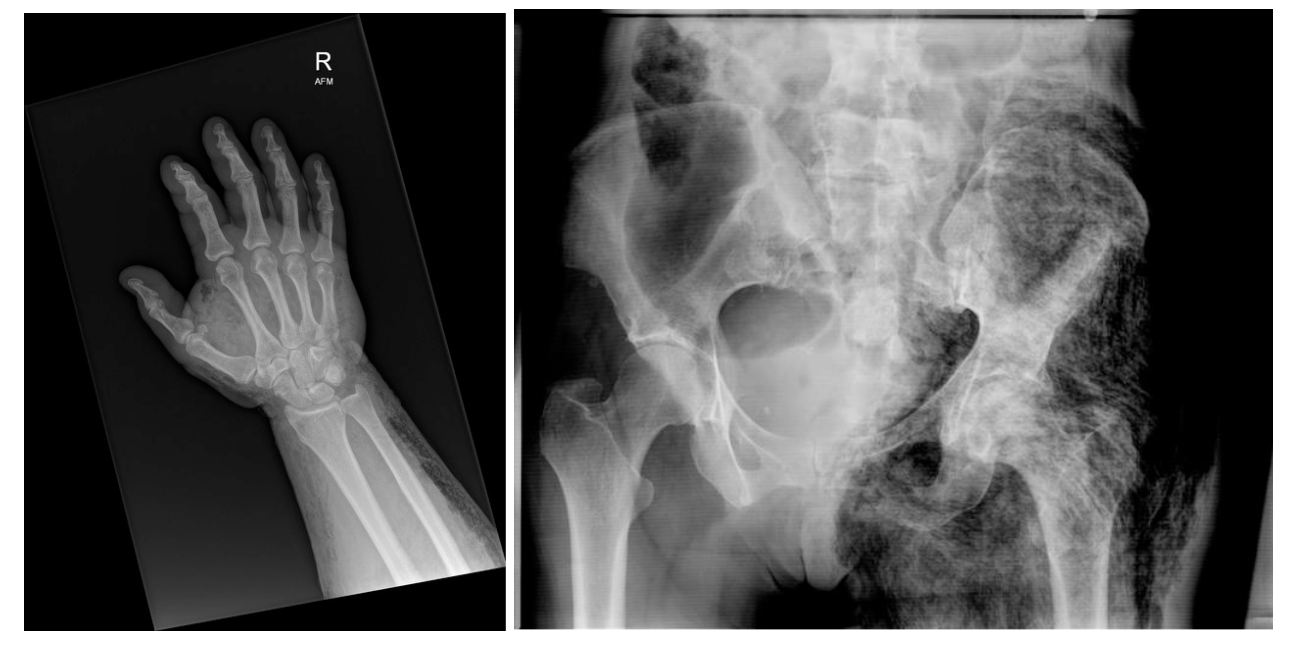

- X-ray

- sensitivity of 48.9%, specificity of 94.9%

- x-ray may reveal gas in subcutaneous tissues but may miss deep fascial gas

- Computed Tomography with Contrast

- sensitivity of 88.5% and specificity of 99.3%

- CT may reveal fascial thickening of deep fascial planes, nonenhancing deep fascia on contrast imaging suggesting necrosis, edema, and gas

- gas is highly specific but only found in ~1/3 of all necrotizing soft tissue infections

- patients might have concomitant kidney disease, preventing from them from receiving IV contrast

- MRI

- sensitivity of nearly 93%

- MRI may reveal extensive thickening of intermuscular fascia with an appearance suggesting incomplete vascularization

- presence of gas is highly specific but only found in ~1/3 of all necrotizing soft tissue infections

- limited resource and significant delay to treatment

- Ultrasonography

- unclear sensitivity/specificity

- Ultrasound may reveal fluid collections along fascial plane, fascia irregularity, subcutaneous air

- superficial hyperechogenicity may block deeper findings

- user-dependent

Management:

Initial steps:

- ABCs and IV/ O2/ monitor as these patients may present as critically ill patients or decompensate quickly

- supportive measures including aggressive fluid resuscitation as well as transfusion of platelets and red blood cells as needed (to correct hemolytic anemia)

- laboratory studies including typical pre-operative studies

- avoid vasoconstrictors if possible as it will further decrease perfusion to already compromised tissue

Antibiotics:

- effectiveness is very limited when used alone given vascular supply to diseased tissue is damaged, thereby preventing adequate delivery of antibiotics

- empiric antimicrobials should be administered immediately / promptly

- Necrotizing fasciitis infections tend to be polymicrobial or many times driven by Group A Streptococcus (S. pyogenes)

- Beta-lactam / betalactamase inhibitor such ampicillin-sulbactam, or piperacillin-tazobactam (if severely ill and/or suspect pseudomonas), or ceftriaxone + metronidazole; goal is to ensure anaerobic, gram-negative and Strep species coverage

- add vancomycin for MRSA coverage or if severely ill

- add clindamycin for additional action particularly against Group A Streptococcus

- action against M- protein of some streptococcus species which help reduce its virulence by preventing exotoxin release (anti-toxin effect)

- Remember to update tetanus prophylaxis

Surgery :

- Gold standard of therapy is “source control” in order to decrease bacterial burden and to stop further damage: urgent surgical consult is critical

- interventions may include fasciotomy, debridement, and/or amputation depending on extent of disease

- fasciotomies may be indicated as ischemic tissue and subsequent inflammation can cause elevated compartment pressures

- mortality significantly increased if surgery is delayed for >24 hours

- depending on extent and location of ischemic tissue, may require several consulting services including general surgery, plastic surgery, oral surgery, urology

Adjunct Therapies:

- hyperbaric oxygen

- previous review of 57 studies published in 2003 suggests there was questionable benefit but without significant parameters to suggest methods and timing of treatment

- studies looked at all wounds which included some necrotizing soft tissue infections

- Cochrane review in 2015 failed to identify any studies that specifically addressed the evidence of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the setting of necrotizing fasciitis

- controversial, should not delay operative treatment

- previous review of 57 studies published in 2003 suggests there was questionable benefit but without significant parameters to suggest methods and timing of treatment

- intravenous immune globulin

- based on ability to neutralize the extracellular toxins released by bacteria

- 2017 review study of 4127 patients by IDSA shows that patients with necrotizing fasciitis and vasopressor-dependent shock were infrequently given IVIG

- no impact on in-hospital mortality or length of stay compared to standard care including surgical debridement and antibiotics

Disposition:

- Operating Room

- as discussed, debridement and exploration is definitive treatment

- in conjunction and discussion with your surgical colleagues

- ICU

Key Points:

- Necrotizing soft tissue infection has the hallmarks of a scary disease: easy to miss and hard to diagnose

- Certain risk factors predispose likelihood of developing necrotizing soft tissue infections but young and healthy individuals are susceptible as well

- Physical exam findings of crepitus, pain out of proportion and hypotension along with cellulitic skin changes are concerning for necrotizing soft tissue infection

- Imaging can be helpful in clinching the diagnosis, but not so much for ruling it out

- If concerned, obtain surgical consult early as they will be helpful in early diagnosis and treatment; patients can deteriorate quickly

Special thanks to our ID Editor, Dr. Angelica Kottkamp

References:

Carbonetti F, Cremona A, Carusi V, Guidi M, Iannicelli E, Di Girolamo M, Sergi D, Clarioni A, Baio G, Antonelli G, Fratini L, David V. The role of contrast enhanced computed tomography in the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis and comparison with the laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis (LRINEC). Radiol Med. 2016 Feb;121(2):106-21. doi: 10.1007/s11547-015-0575-4. Epub 2015 Aug 19. PMID: 26286006.

Coyle EA; Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Targeting bacterial virulence: the role of protein synthesis inhibitors in severe infections. Insights from the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(5):638-642. doi:10.1592/phco.23.5.638.32191

Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, et al. Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infection: Diagnostic Accuracy of Physical Examination, Imaging, and LRINEC Score: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Surg. 2019;269(1):58-65. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002774

Kadri SS, Swihart BJ, Bonne SL, et al. Impact of Intravenous Immunoglobulin on Survival in Necrotizing Fasciitis With Vasopressor-Dependent Shock: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis From 130 US Hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(7):877-885. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw871

Kelly EW. In: Tintinalli JE, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Stapczynski J, Cline DM, Thomas SH. eds.Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 9ehttps://accessemergencymedicine-mhmedical-com.ezproxy.med.nyu.edu/content.aspx?bookid=2353§ionid=220292152

Levett D, Bennett MH, Millar I. Adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen for necrotizing fasciitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1(1):CD007937. Published 2015 Jan 15. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007937.pub2

Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine – Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol Eighth edition. Saunders; 2014. Accessed January 22, 2021. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.med.nyu.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=596434&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Stevens DL, Bryant AE. Necrotizing Soft-Tissue Infections. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2253-2265. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1600673

Tso DK, Singh AK. Necrotizing fasciitis of the lower extremity: imaging pearls and pitfalls. (2018) The British journal of radiology. 91 (1088): 20180093. doi:10.1259/bjr.20180093 – Pubmed

Wang C, Schwaitzberg S, Berliner E, Zarin DA, Lau J. Hyperbaric oxygen for treating wounds: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2003;138(3):272-280. doi:10.1001/archsurg.138.3.272