Background

- Definition

- Combination of proximal fibula fracture (commonly spiral) associated with an unstable ankle joint injury (disruption of the ankle mortise). It involves a ligamentousinjury (distal tibiofibular syndesmosis +/- deep deltoid ligament) and/or fracture of the medial/posterior malleolus. The fibula fracture usually occurs in the proximal third, but can be as distal as 6 cm above the ankle joint.

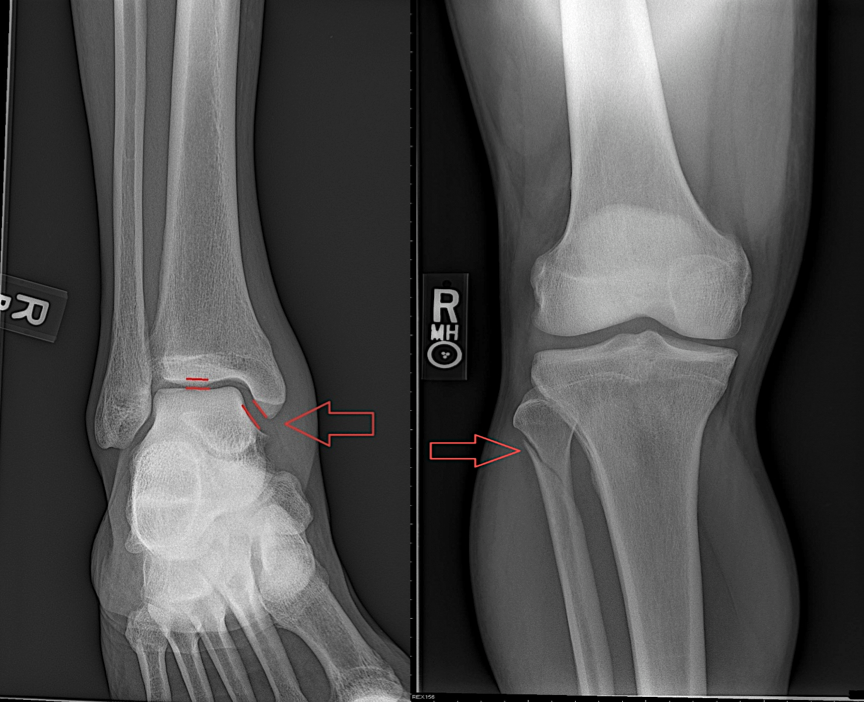

MAISONNEUVE FRACTURE: Medial clear space widening (deep deltoid ligament disruption) with associated proximal fibular fracture.

- Tibiofibular syndesmosis: fibrous interosseous membrane connecting the tibia/fibula along their entire length. A Maisonneuve injury disrupts this intimate structural relationship, leading to ankle joint instability.

- First identified by French surgeon J.G. Maisonneuve via cadaveric experiments, it was demonstrated how an external rotation force applied to the ankle joint can also precipitate a proximal fibula injury.

- This injury occurs in ~5% of all ankle fractures.

Mechanism

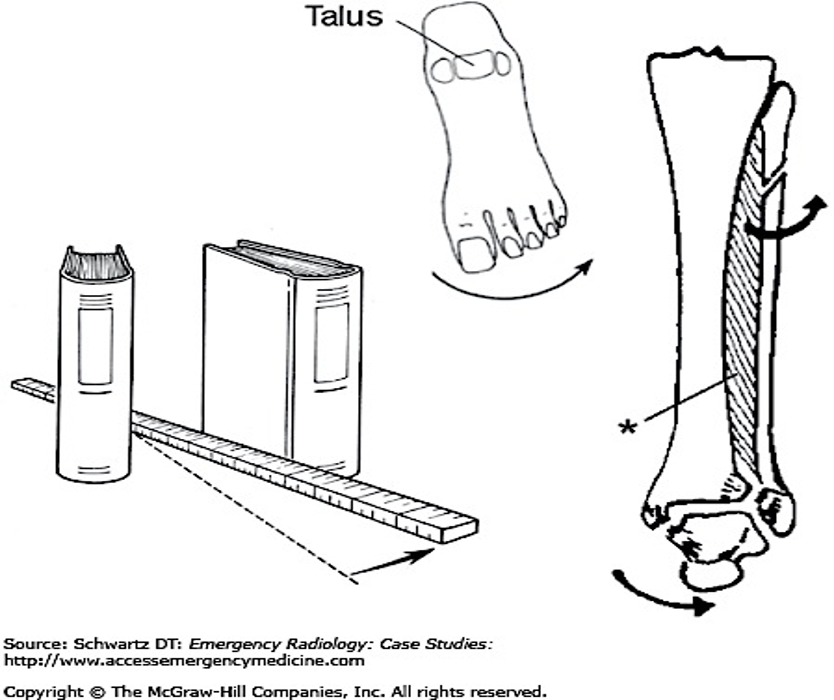

- External rotation of the foot causes lateral motion of the talus, eventually leading to disruption of the ankle mortise. This structural collapse begins at the medial ankle, travels proximally and laterally traversing the interosseous membrane, and eventually exits across the proximal fibula.

- Medial ankle pathology includes fractures of the medial malleolus and/or rupture of the deep deltoid ligament. Posterior malleolar injuries can also occur.

- Classified as a pronation-external rotation (PER) injury in the Lauge-Hansen ankle injury classification or Danis-Webber C

- Described by Maisonneuve as the rotation of a ruler placed between two books: “As the ruler rotates, it separates the two books.”

- Isolated fibula fractures from direct force to the lateral fibula should be differentiated from external rotation injuries, whereby there is no concern for associated ankle joint instability.

MECHANISM OF INJURY WITH MAISONNEUVE ANALOGY

*Interosseous ligament/membrane

Physical Exam

- Examine all patients with ankle injuries for tenderness along the entire length of the fibula

- High clinical suspicion is required as many patients may not complain of knee or calf pain due to the distracting nature of the initial ankle injury. (See Table 1 for when to suspect Maisonneuve injuries)

- “Squeeze” Test: compression of the tibia/fibula just above the ankle joint. Ankle and/or distal lower leg pain is considered a positive test, suggesting syndesmotic injury.

“SQUEEZE” test: compression of the

tibia/fibula elicits pain in the ankle/lower leg.

- The common peroneal nerve courses over fibular head, thus a meticulous neurologic exam is critical. Weakness of ankle dorsiflexion/subtalar joint (foot) eversion and/or numbness along the lateral lower leg/dorsum of the foot should raise clinical suspicion for a Maisonneuve injury.

X-Rays

- In addition to imaging of the ankle, tib-fib x-rays should also be obtained to evaluate the entire length of tibia/fibula.

- Ankle radiographs can appear “normal” (may only have an occult deep deltoid ligament injury with minimal medial clear space widening and/or isolated posterior tubercle disruption)

- A “stress” view of the ankle joint can assist in identifying injury to the deep deltoid ligament with associated ankle joint instability.

- A mechanical stress view is performed with the patient supine/sitting upright with the lower leg in 15-20° internal rotation. Following stabilization of the lower leg, a supination/external rotation force is then applied to the ankle.

Mechanical Stress View

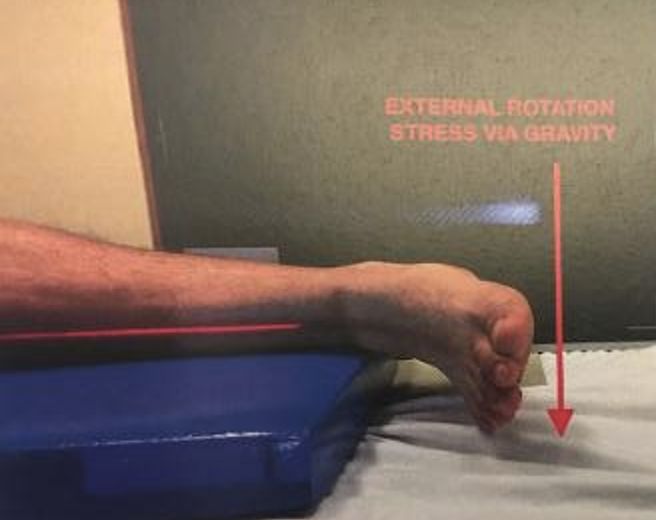

- Alternatively, a “gravity” stress view can be performed, minimizing overall patient apprehension/discomfort.

- It is accomplished with the affected side lateral foot facing down, and the ankle joint in neutral position. Medial clear space widening will be evident as the talus displaces laterally via gravity if a syndesmotic injury is present.

- If no instability is identified, the proximal fibula fracture is not considered a “true” Maisonneuve fracture, and often can be treated conservatively.

Gravity Stress View

Table 1. When to suspect Maisonneuve fracture:

|

|

|

Adapted from Schwartz, DT: Emergency Radiology: Case Studies

ED Management

- Maisonneuve fractures are associated with ankle mortise instability, and typically require surgical repair.

- Failure to recognize and treat this ankle instability can lead to chronic pain and long-term disability.

- Affected patients should be “reduced”, placed in a short leg splint, remain non-weight bearing, with emergent orthopedic follow-up for anticipated surgical intervention

- “Open” injuries and/or fractures with neurovascular compromise require urgent orthopedic evaluation and management.

Take-Home Points

- All patients who present with ankle injuries should be examined for proximal fibular pathology.

- Patients with tenderness over the proximal fibula should receive imaging of the entire length of the tibia/fibula to assess for potential Maisonneuve injuries.

- Maisonneuve fractures should be suspected with injuries to the medial/posterior malleolus and/or deep deltoid ligament without an associated distal fibular fracture.

- “Stress” views may be necessary to identify subtle ankle instability with high clinical suspicion based upon patient presenting history/physical exam findings.

- Maisonneuve fractures should be immobilized, remain non-weight bearing and have expedited orthopedic follow-up. These injuries generally require operative intervention for enduring stabilization.

- Missed injuries can lead to chronic pain, joint instability, diminished biomechanical function and associated degenerative changes.

References

Heckman, J. D., McKee, M., McQueen, M. M., Ricci, W., & Tornetta III, P. (2014). Rockwood and Green’s fractures in adults. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Millen, J.C., Lindberg, D. Maisonneuve fracture. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(1):77‐78.

Purcell, D, et al: “Emergency Orthopedics Handbook”. Springer. 2019

Schwartz, D. (2007). Emergency radiology: case studies. McGraw-Hill Prof Med/Tech.

Stufkens, S.A., van den Bekerom, M.P., Doornberg, J.N., van Dijk, C.N., & Kloen P. Evidence-based treatment of maisonneuve fractures. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(1):62‐67.

Tintinalli, J. (2015). Tintinalli’s emergency medicine A comprehensive study guide. McGraw-Hill Education.