INTRODUCTION

- The most common cause of intestinal obstruction in children <2 years of age

- Peak incidence is between 3 months and 1 year

- 80% of cases occurring <2 years of age

- Occurs when a segment of bowel “telescopes” into another segment of bowel

- Ileocecal intussusception is the most common type

- Lymphoid hyperplasia (Peyer’s patches) is the etiology most commonly proposed

- In older children and in those with recurrence, a pathologic “lead point” may be present. These include:

- Intestinal polyps

- Meckel’s diverticulum

- Tumors (e.g. lymphoma)

- Intestinal duplications

- Henoch-Schonlein Purpura colitis is a distinct risk factor for intussusception (commonly ileoilial intussusception)

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

- Sign/Symptom profile dependent upon age group (Mandeville 2012, PMID: 22929138)

| Signs/Symptoms | <12 mo | 12-36 mo | >36 mo |

| Abdominal pain | 90% | 96% | 97% |

| Emesis | 94% | 79% | 64% |

| Guaiac-positive stool | 83% | 60% | 67% |

| Grossly bloody stools | 83% | 41% | 37% |

| Irritability | 71% | 51% | 14% |

| Bilious emesis | 48% | 24% | 31% |

| Lethargy | 47% | 26% | 13% |

| Diarrhea | 38% | 34% | 41% |

| Constipation | 13% | 24% | 25% |

| Abdominal mass | 33% | 23% | 22% |

| Abdominal distention | 25% | 18% | 21% |

- Bilious vomiting and lower gastrointestinal bleeding are late findings

- “Currant jelly” stools occur in less than 50% of cases

- Mental status changes described as alternating periods of lethargy and irritability

- Sausage-shaped mass may be palpated in the right upper quadrant

- Stool exam for blood may or may not be positive

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

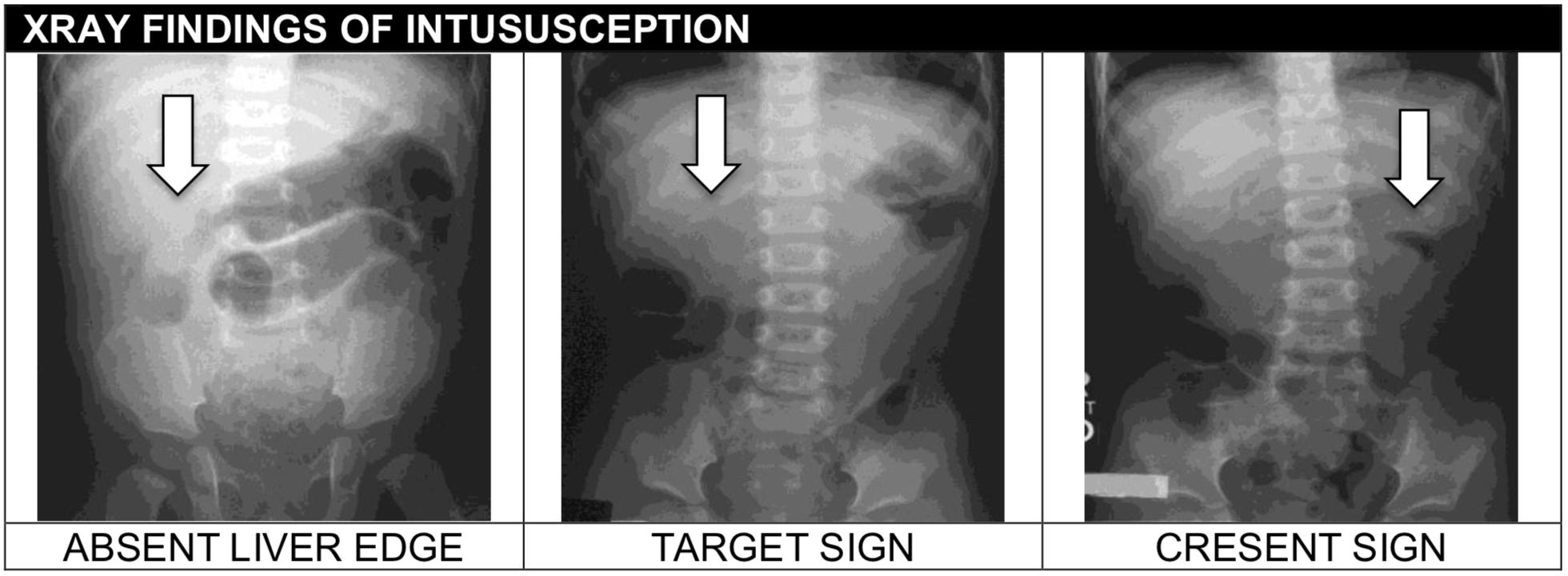

- Abdominal XR

- May be helpful to rule in but not rule out

- The most common finding is “non-specific bowel gas pattern”

- May reveal signs of obstruction or a soft tissue mass

- Specific findings include:

- Absent liver edge sign (soft tissue mass in the RUQ)

- Target sign (intussuceptum seen in a transverse plane)

- Crescent sign (the head of the intussusception)

- Presence of air in the ascending colon on a three view XR series (prone, supine and lateral decubitus) may effectively rule out intussusception in patients with low suspicion for the diagnosis (Roskind, PMID: 22929143)

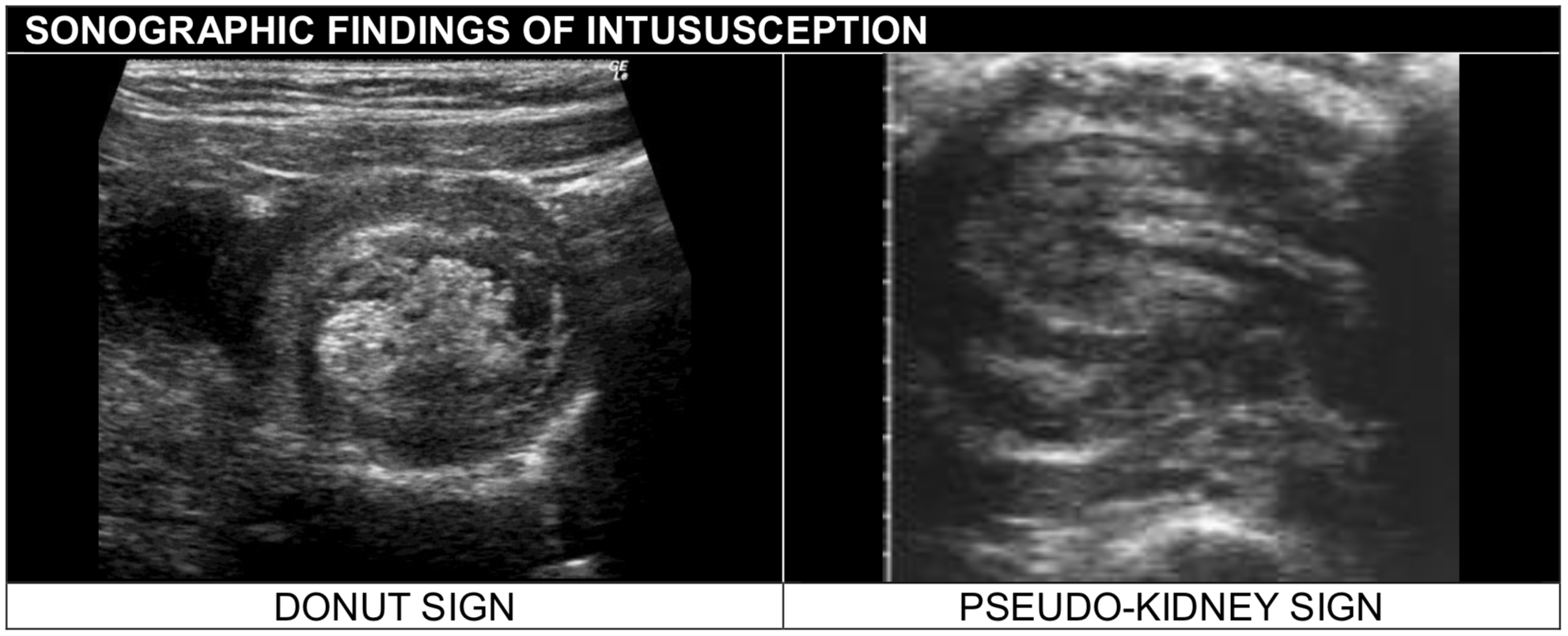

- Ultrasound

- Diagnostic modality of choice

- In the transverse cut, one can see a ring of bowel within bowel (donut sign)

- The longitudinal appearance, one can see the appearance of multiple layers (submarine sandwich or pseudokidney sign)

- A negative ultrasound by an experienced radiologist may limit the need for a contrast enema

- Ultrasound performed / interpreted by pediatric and emergency radiologists (Hryhorczuk 2009, PMID: 19657636)

- Had a sensitivity of 97.9% and specificity of 97.8% (NPV = 99.7%)

- POCUS performed by relatively novice pediatric emergency medicine faculty and fellows (Riera2012, PMID: 22424652)

- Had a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 97%

MANAGEMENT

- A contrast enema may be both diagnostic and therapeutic

- Air enemas decrease the risk of contrast material peritonitis in the case of perforation with similar rates of success

- Success rates for hydrostatic reduction of intussusception via enema have been reported as high as 80-90%

- Successful reduction is indicated by flow of air into proximal bowel

- Complications:

- Perforation

- Partial reduction

- Reduction of a necrotic segment of bowel

- Missing a pathologic lead point

- A surgeon should be available immediately in case the bowel becomes perforated during the procedure or the reduction is unsuccessful

- Success rates for hydrostatic reduction of intussusception via enema have been reported as high as 80-90%

- Patients who have had their intussusception reduced are typically admitted to the hospital for a period of observation though a recent study has suggested that admission may not be necessary

- Rates of both late and early recurrence (approximately 15%) were similar in the group observed in the ED for 4 hours and as an inpatient for 24 hours (Mallicote 2017, PMID: 28969892)

- Recurrence is rare

- Over a 10 year interval, 245 episodes of intussusception occurred in 210 patients. Six patients (2.45%) had a recurrent ileocolic intussusception with 7-28 after initial successful reduction. (Simanovsky 2019, PMID: 30143943)

REFERENCES

Hryhorczuk AL, Strouse PJ. Validation of US as a first-line diagnostic test for assessment of pediatric ileocolic intussusception. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(10):1075-9. PMID: 19657636

Mallicote MU, Isani MA, Roberts AS, Jones NE, Bowen-Jallow KA, Burke RV, et al. Hospital admission unnecessary for successful uncomplicated radiographic reduction of pediatric intussusception. Am J Surg. 2017;214(6):1203-7. PMID: 28969892

Mandeville K, Chien M, Willyerd FA, Mandell G, Hostetler MA, Bulloch B. Intussusception: clinical presentations and imaging characteristics. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(9):842-4. PMID: 22929138

Riera A, Hsiao AL, Langhan ML, Goodman TR, Chen L. Diagnosis of intussusception by physician novice sonographers in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(3):264-8. PMID: 22424652

Roskind CG, Kamdar G, Ruzal-Shapiro CB, Bennett JE, Dayan PS. Accuracy of plain radiographs to exclude the diagnosis of intussusception. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(9):855-8. PMID: 22929143

Simanovsky N, Issachar O, Koplewitz B, Lev-Cohain N, Rekhtman D, Hiller N. Early recurrence of ileocolic intussusception after successful air enema reduction: incidence and predisposing factors. Emerg Radiol. 2019;26(1):1-4. PMID: 30143943