Definition: An acute infection and inflammation of the supraglottic soft tissue structures, which can lead to airway occlusion over a relatively short period of time, typically 2-7 days. Because of the possibility for rapid decompensation to airway occlusion, this is considered an ENT emergency.

Epidemiology

- Uncommon disorder

- Incidence of 3-5:100,000 per year. Mortality between 7-20%.

- Mean age of those affected is 55. Child:adult ratio of 0.3:1.

- Risk factors include smoking, diabetes, immunocompromise.

- Broad range of causative organisms, but most commonly caused by various strep and staph species.

No longer a children’s disease

In medical school, most of us learned about epiglottitis during our pediatric lectures, where we were taught to keep our eyes out for that rare and weird child with the “3 D’s”:

- Drooling

- Dysphagia

- Distress

and speaking in a “hot potato voice.” For most of modern history, epiglottitis was primarily a disease of children, predominantly caused by Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib). Prior to the introduction of the Hib vaccine in the 1980s, the child:adult ratio of those diagnosed with epiglottitis was 2.6 to 1. By 1995 the vaccine had dramatically decreased the incidence of pediatric Hib infections and flipped the child:adult ratio to 0.3 to 1. (Shah 2010)

Due to the success of the Hib vaccine in decreasing the incidence of pediatric illness, epiglottitis now mainly affects adults, and its initial presentation is usually more subacute. (Cheung 2009, Ng 2008)

Epiglottitis is difficult to diagnose, and some studies have estimated that it is missed on initial presentation as much as 80% of the time. The initial symptoms of epiglottitis may be identical to a viral URI or strep throat, but can progress to airway compromise over a relatively short period of time. Adding to the difficulty in diagnosis, most patients have no external swelling or erythema. The oropharynx appears normal, since the affected area is out of view in the supraglottic space.

| Sore throat | 94% |

| Dysphagia | 88% |

| Odynophagia | 62% |

| Fever | 41% |

| Dyspnea | 30% |

| Cough | 7% |

| Muffled voice | 6% |

| Stridor | 1% |

| Drooling | 1% |

NB: maintain a high suspicion for epiglottitis in a patient who comes to the ER for a second time for a worsening sore throat, and any other symptoms of dysphagia, hoarseness, or pain to palpation of the neck, especially if there are no obvious findings in the oropharynx.

Differential diagnosis

Diphtheria

Ludwig’s angina

Diagnosis

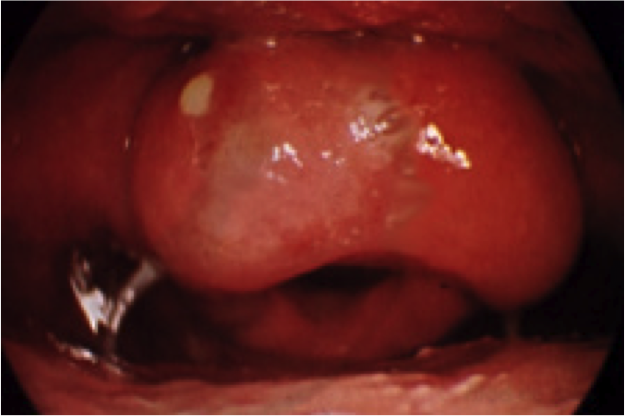

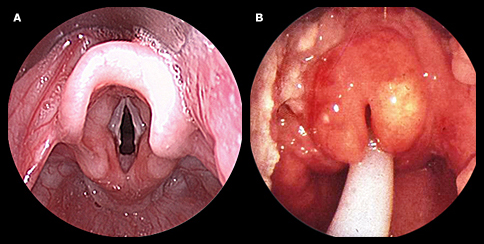

- Fiberoptic nasal layngoscopy

- Gold standard diagnostic test, and required for any patient you suspect may have epiglottitis

- Lateral neck x-ray

- Sensitivity: 90% sensitive (Rothcock 1990)

- Classic finding: “thumbprint” sign (epiglottis thickened with inflammation and has a thumb-like appearance)

CT of the neck is similarly sensitive, and may be useful if the diagnosis is unclear. (Rothrock 1990)

Management:

- Airway

- For patients with advanced inflammation, prophylactic intubation may be necessary. Involve consultants early for a possible awake intubation in the OR, and with preparations to convert to a surgical airway, if necessary.

- Avoid supraglottic ventilation (LMAs, King LT), as it may compress a distorted or swollen epiglottis.

- Heliox can improve work of breathing and work as a temporizing measure.

- Antibiotics and adjunct treatments

- Ampicillin-sulbactam or Amoxicillin-clavulanate are the preferred initial antibiotic recommendations (Guldfred 2008)

- Vancomycin should be added for the critically ill patient in whom MRSA is a possibility.

- NSAIDs for pain and inflammation control.

- In cases with significant inflammation, steroids are a possible adjunct. Studies on their efficacy in epiglottitis are inconclusive, however.

- Disposition

- All patients diagnosed with epiglottitis should be admitted for monitoring to ensure improvement.

For patients with advanced inflammation seen on laryngoscopy, or patients with any respiratory symptoms, the ICU may be appropriate for closer monitoring.

Take home points:

- Epiglottitis has demonstrated a resurgence in the adult population. It is no longer a pediatric only disease.

- The classic presentation of epiglottitis (3Ds of drooling, dysphagia and distress) is uncommon

- Epiglottitis should be high on your differential for the bounce-back patient who continues to complain of worsening sore throat

- Definitive diagnosis is made by flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy

- Be ready for a difficult airway.

References:

Shah RK, Stocks C. Epiglottitis in the United States: national trends, variances, prognosis, and management. Laryngoscope. 2010; 120:1256–1262. PMID: 20513048

Cheung CS, Man SY, Graham CA, Mak PS, Cheung PS, Chan BC, Rhainer TH. Adult epiglottitis: 6 years experience in a university teaching hospital in Hong Kong. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009; 16:221–22. PMID: 19282760

Ng HL, Sin LM, Li MF, Que TL, Anandaciva S. Acute epiglottitis in adults: a retrospective review of 106 patients in Hong Kong. Emerg Med J. 2008; 25:253–255. PMID: 18434453

Tamir, Marom, et al. Adult supraglottitis: changing trends. European Archives of oto-rhinolaryngology and Head and Neck. 2014; 272:2464. PMID: 25528553

Rothrock SG, Pignatiello GA, Howard RM. Radiologic diagnosis of epiglottitis: objective criteria for all ages. Ann Emerg Med. 1990: 19(9):978-82. PMID: 2393182

Guldfred LA, Lyhne D, Becker BC. Acute epiglottitis: epidemiology, clinical presentation, management and outcome. J Laryngol Otol. 2008; 122:818–823. PMID: 17892608