Definition

-

Fracture of the clavicle, commonly referred to as the “collarbone”

Epidemiology

- 2-4% of all fractures, 44-66% of all shoulder fractures

- Most often seen in young, active individuals

Mechanism

- Fall onto shoulder in approximately 85% of cases, direct trauma 5-10%, and fall on outstretched hand (“FOOSH”) 5-10%

Physical Exam

- Patients often present holding the affected arm in flexed abduction and internal rotation

- Gross deformity frequently appreciable in addition to focal tenderness and swelling

- Pain exacerbated by shoulder movement

- High-Risk Features:

- Tenting of skin – possible impending open fracture

- Decreased breath sounds on ipsilateral side – possible pneumothorax

- Neurovascular deficits

Allman Classification1

- Group I – Middle 1/3 Clavicle Fracture (80% of all clavicle fractures)

- Majority are non-operative except in cases of 100% displacement (essentially, a fracture where the two fragments do not overlap in a plane)

- Group II – Lateral 1/3 Clavicle Fracture (10-15%)

- Operative indication depends on location of fracture(s) relative to the ligamentous attachments. Essentially, an unstable clavicle may require surgery

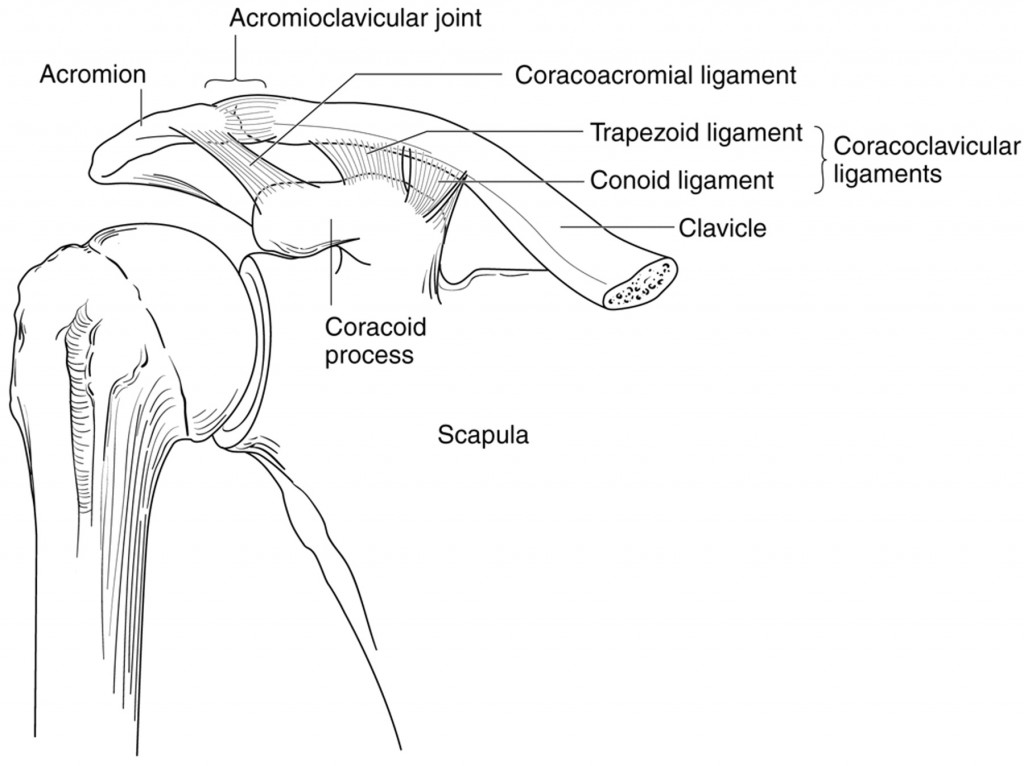

- Neer Classification:

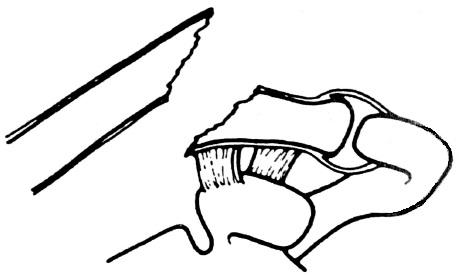

- Type I: Minimally-displaced fracture either lateral to the conoid and trapezoid ligaments or interligamentous

- Type IIA: Distal fragment attached to conoid and trapezoid

- Unstable, thus operative

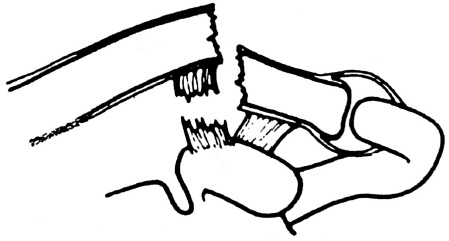

- Type IIB: Conoid ligament torn, distal fragment attached to trapezoid

- Unstable, thus operative

- Type III: intra-articular fracture of AC joint

- Type IV: physis fracture in children / young adults

- Type V: comminuted fracture

- Unstable, thus operative

- Group III – Medial 1/3 Clavicle Fracture (5-8%)

- Non-operative if anteriorly displaced, fixation indicated if posteriorly displaced (rare) with physis involvement (up to age 25 because sternal end is last ossification site to fuse) or instability based on costoclavicular ligaments

- Must assess for possible airway or great vessel involvement, which are indications for emergent surgery

Imaging

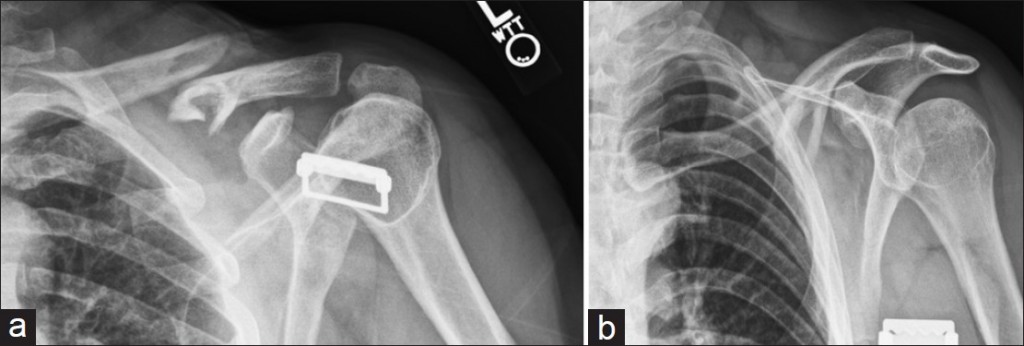

- AP of bilateral shoulders (a CXR will sometimes suffice) to measure clavicular shortening

- Dedicated “clavicle films” usually include cephalad and caudal tilt to assess inferior/superior and anterior/posterior displacement, respectively2

- Ultrasound is often sufficient, especially in children, for making the diagnosis3 but may not be adequate in cases of distal or proximal fractures. Also not ideal imaging modality in operative candidates

Management & Prognosis

- Nonoperative management entails sling immobilization for up to 6-10 weeks total to help with pain. Early ROM and strengthening exercises are important:

- Nonunion in up to 5% of cases, higher risk if:

- Group II (up to half of cases)

- 100% displacement

- Comminution

- Shortening >2 cm

- Advanced age

- Poorer cosmesis

- Decreased shoulder strength is seen in cases of displaced midshaft fractures with > 2 cm of shortening (part of the reason surgery is recommended for these patients)

- Nonunion in up to 5% of cases, higher risk if:

- Operative management (ORIF):

- Improved functional outcome and less pain

- Decreased healing time

- Decreased rate of malunion

- Improved cosmesis

Take-Home Points

- Clavicle fractures are common and the diagnosis is often apparent based on history and physical exam alone

- The majority of clavicle fractures can be managed non-operatively but operative indications depend on the fracture’s location, stability, and amount of displacement for midshaft fractures

- Emergent surgery is only indicated in cases of airway or great vessel involvement, which is extraordinarily rare

References

- Allman, Fred L. “Fractures and ligamentous injuries of the clavicle and its articulation.” The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery 49.4 (1967): 774-784.

- Harris, Joshua D., and James C. Latshaw. “Improved clinical utility in clavicle fracture decision-making with true orthogonal radiographs.” International journal of shoulder surgery 6.4 (2012): 130.

- Cross KP, Warkentine FH, Kim IK, Gracely E, Paul RI (July 2010). “Bedside ultrasound diagnosis of clavicle fractures in the pediatric emergency department”. Acad Emerg Med 17 (7): 687–93. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00788.x. PMID 20653581

- Egol, Kenneth A., Kenneth J. Koval, and Joseph David Zuckerman. Handbook of fractures. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.