Background

- Viral upper respiratory prodrome followed by increased respiratory effort and wheezing in children less than 2 years of age

- Acute, viral-induced inflammation and edema of the airways of the lower respiratory tract resulting in airway obstruction

- Smooth muscle constriction appears to play a limited role

- The most common lower respiratory tract infection in children under 2 years of age

- Peak age between 2 and 6 months

- A leading cause of infant hospitalization

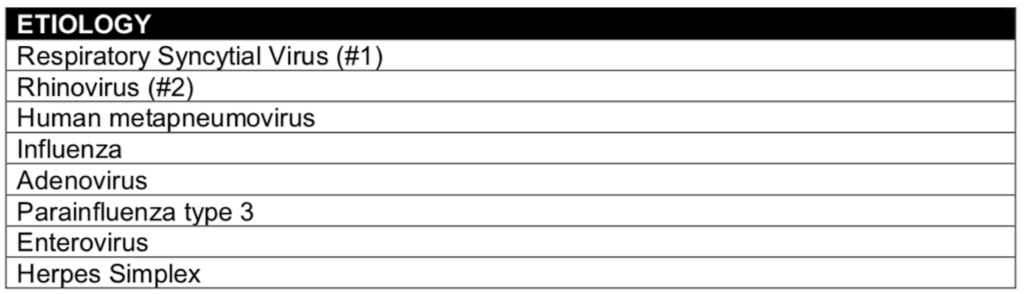

- RSV causes the majority of cases

- Most common in the late fall and winter seasons

- Co-infection with more than one virus may occur in up to 30% of cases and a viral infection with a concomitant bacterial infection can also occur

- Apnea can occur in 5% of hospitalized children (Schroeder 2013, PMID: 24101759)

- Risk factors for severe disease

- Infants born prematurely (<37 weeks)

- Neonates (<6 weeks)

- Those with congenital heart disease

- Chronic lung disease such as: Cystic fibrosis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, congenital pulmonary anomaly

- Primary immunodeficiency or receiving immunosuppressant therapy

Clinical Findings

- Typically with cough and coryza for 1 to 2 days

- Progresses to lower respiratory illness including wheezing, worsening cough and tachypnea on days 5 to 7 and then gradually resolves

- Cough typically resolves at 2 weeks but complete resolution can take up to 4 weeks

- Fever may also be present

- The degree of respiratory symptoms can cause poor feeding and lead to dehydration

- Co-infections may include: Conjunctivitis, pharyngitis and otitis media

- Significant accessory muscle use, nasal flaring, grunting and head bobbing in younger infants indicate respiratory distress and the potential for pending respiratory failure

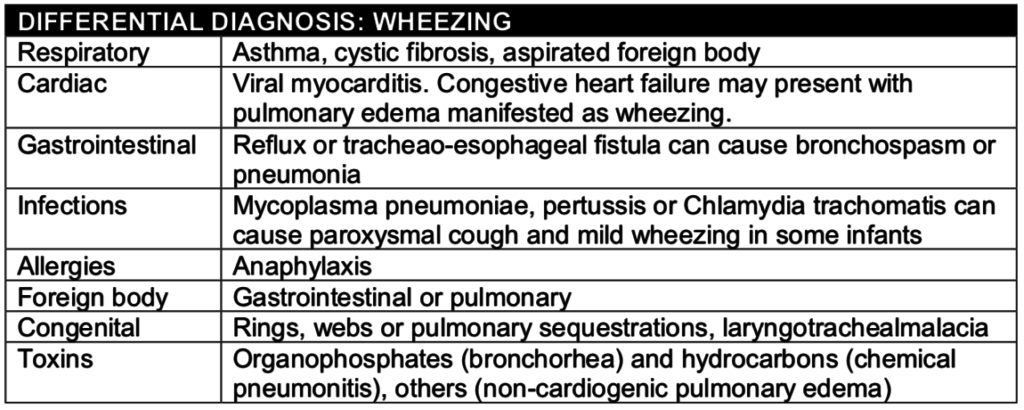

- Auscultation finding can include expiratory wheezing, prolonged expiration and both fine and coarse rales

Diagnosis

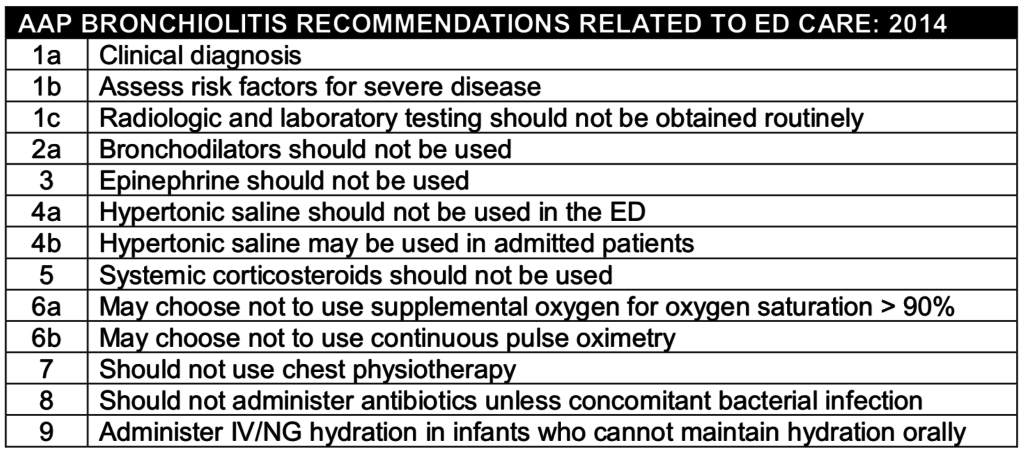

- Clinical diagnosis

- Rapid viral testing is of limited usefulness except for epidemiological surveillance, cohorting on inpatient wards to reduce nosocomial spread

- Oxygen saturation and end-tidal CO2 monitoring in conjunction with respiratory rate, respiratory effort and mental status can be used to determine the presence of respiratory failure and the need for mechanical ventilation

Radiography:

- Chest radiographs are not routinely recommended to diagnose bronchiolitis

- Can exclude other causes of wheezing such as foreign body aspiration, pneumonia or congestive heart failure

- Chest XRAY findings in bronchiolitis may include:

- Hyperventilation with increased interstitial markings

- Peri-bronchial cuffing

- Patchy infiltrates / atelectasis

Laboratory Testing:

- Testing may be helpful in detecting co-infection with bacterial pathogens in febrile infants.

- Infants less than 60 days with fever should be evaluated for serious bacterial infection such as urinary tract infection.

- The prevalence of bacteremia (1-2%) and UTI (1-5%) are lower than those without bronchiolitis (Levine 2004, PMID: 15173498)

Management

- Bronchiolitis is a self-limited illness, typically requiring only supportive care

- Oxygen:

- Oxygen should be provided in the least invasive method possible to maintain oxygen saturation greater than 90%.

- Artificially elevated oxygen saturations by 3% resulted in lower admission rates without an increase in complications (Schuh 2014, PMID: 25138332)

- A study of infants discharged from the emergency department with home oxygen saturations monitors with the display and alarms turned off revealed that a majority of infants (64%) had desaturations to less than 90% for > 1 minute (Principi 2016, PMID: 26928704)

- The presence of desaturations did not result in an increase in unscheduled health care visits or hospitalization

- Nasal Suctioning:

- Nasal suctioning may be attempted, though there is a paucity of data supporting or refuting this practice

- Hydration:

- Bronchiolitis is associated with an increase in antidiuretic hormone resulting in fluid overload and hyponatremia

- Hypotonic intravenous solutions may exacerbate this process and should be avoided

- Bronchodilators:

- Routine use of nebulized bronchodilators does not alter clinical course (Gadomski 2014, PMID: 24937099)

- A single trial of inhaled bronchodilators may be attempted in patients with severe disease

- Nebulized Hypertonic Saline:

- The 2014 AAP Guidelines recommend that nebulized hypertonic saline (HS) may be administered in inpatients but should not be administered in the emergency department

- Studies on the benefits and adverse effects of HS have yielded mixed results (Heikkilä 2018, PMID: 29266869; Zhang 2015, PMID: 26416925; Angoulvant 2017, PMID: 28586918)

- Corticosteroids:

- Dexamethasone does not affect the rate of hospital, length of hospital stay, subsequent admissions, or adverse events (PECARN 2007, PMID: 17652648)

- One study giving dexamethasone and salbutamol to patients with bronchiolitis and a family history asthma in a first-degree relative was associated with decreased duration of hospitalization (Alansari 2013, PMID: 24043283)

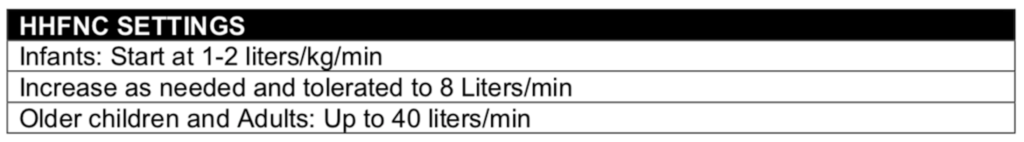

- HHFNC: Humidified High-Flow Nasal Cannula

- The pressure from high flow rates can open the soft palate by separating it from the posterior pharyngeal wall.

- HHFNC is associated with decreased rate of escalation of care (i.e. increase in respiratory support or transfer to an ICU) (Franklin 2018, PMID: 29562151)

- A multicenter, randomized clinical trial included 1,472 infants younger than 1 year of age admitted for bronchiolitis requiring supplemental oxygen

- Treatment failure occurred 12% in the HFNC group an 23% in the standard therapy group (Risk difference: 11%)

- 100% of the escalations in care that occurred in the standard therapy group were started on HFNC and 61% responded

- CPAP: Continuous Positive Airway Pressure

- Delivers a constant level of pressure support (inspiratory and expiratory) without regard to the respiratory cycle

- May be delivered through a variety of interfaces

- Short bi-nasal prongs are preferred in neonates and infants due to the difficulty of maintaining an adequate facemask fit and seal

Disposition

- Criteria for discharge, admission and admission to the pediatric ICU are listed below

- For discharged patients, parents should be educated about signs and symptoms of concern that would warrant seeking care

- Education on the risk of passive smoking, proper hand washing techniques and proper bulb suctioning prior to feeding

- A follow up appointment with their primary care provider should be made

References

Alansari K, Sakran M, Davidson BL, Ibrahim K, Alrefai M, Zakaria I. Oral dexamethasone for bronchiolitis: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):e810-6. PMID: 24043283

Angoulvant F, Bellettre X, Milcent K, Teglas JP, Claudet I, Le Guen CG, et al. Effect of Nebulized Hypertonic Saline Treatment in Emergency Departments on the Hospitalization Rate for Acute Bronchiolitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):e171333. PMID: 28586918

Corneli HM, Zorc JJ, Mahajan P, Shaw KN, Holubkov R, Reeves SD, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of dexamethasone for bronchiolitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(4):331-9. PMID: 17652648

Franklin D, Babl FE, Schlapbach LJ, Oakley E, Craig S, Neutze J, et al. A Randomized Trial of High-Flow Oxygen Therapy in Infants with Bronchiolitis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1121-31. PMID: 29562151

Gadomski AM, Scribani MB. Bronchodilators for bronchiolitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(6):CD001266. PMID: 24937099

Heikkila P, Renko M, Korppi M. Hypertonic saline inhalations in bronchiolitis-A cumulative meta-analysis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2018;53(2):233-42. PMID: 29266869

Levine DA, Platt SL, Dayan PS, Macias CG, Zorc JJ, Krief W, et al. Risk of serious bacterial infection in young febrile infants with respiratory syncytial virus infections. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):1728-34. PMID: 15173498

Principi T, Coates AL, Parkin PC, Stephens D, DaSilva Z, Schuh S. Effect of Oxygen Desaturations on Subsequent Medical Visits in Infants Discharged From the Emergency Department With Bronchiolitis. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(6):602-8. PMID: 26928704

Schroeder AR, Mansbach JM, Stevenson M, Macias CG, Fisher ES, Barcega B, et al. Apnea in children hospitalized with bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):e1194-201. PMID: 24101759

Schuh S, Freedman S, Coates A, Allen U, Parkin PC, Stephens D, et al. Effect of oximetry on hospitalization in bronchiolitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(7):712-8. PMID: 25138332

Zhang L, Mendoza-Sassi RA, Klassen TP, Wainwright C. Nebulized Hypertonic Saline for Acute Bronchiolitis: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):687-701. PMID: 26416925

This article is one of the best, clearest summaries of the treatment of bronchiolitis in the ED that I have read! (And I’ve read a ton…) Thanks

Well done post