Background

- Biliary disease is the third most common cause of acute abdominal pain in the ED (Miettinen 1996, PMID: 8739926; Cervellin 2016, PMID: 27826565)

- No combination of clinical signs and laboratory value can adequately discriminate between biliary pain and biliary disease requiring antibiotic therapy or surgical intervention (Summers 2010, PMID: 20138397)

- In order to determine the need for further therapy or intervention evaluation of biliary disease requires imaging

- Bedside ultrasonography in the Emergency Department has been shown to be effective in detecting choledocholithiasis and cholecystitis, as well as reducing patient length of stay (Blaivas 1999, PMID: 10530660; Summers 2010, PMID: 20138397; Ross 2011, PMID: 21401784)

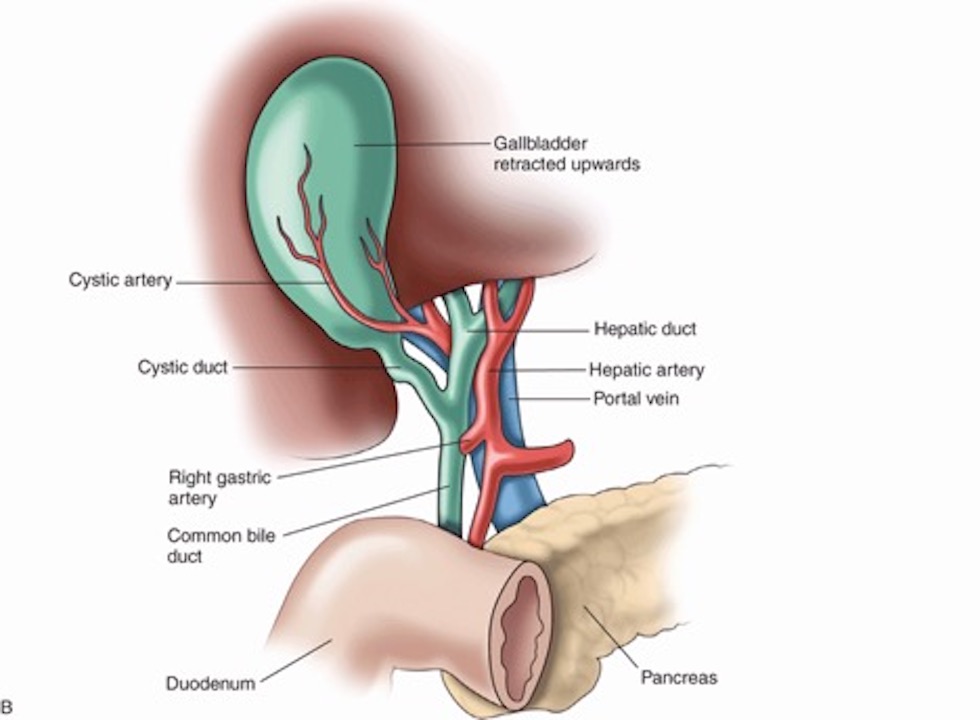

Anatomy

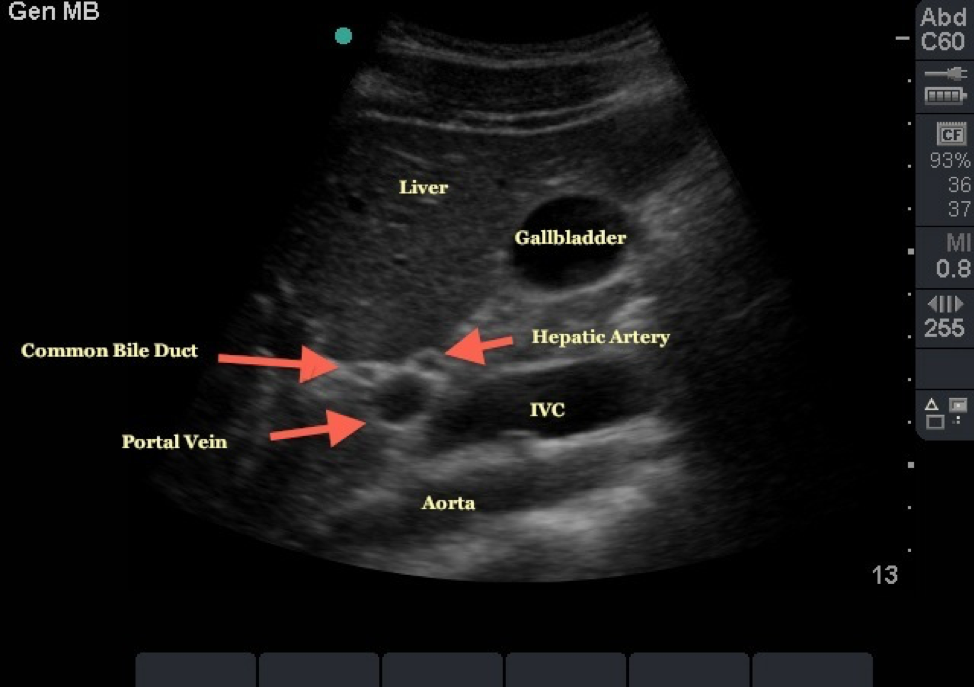

- For bedside biliary ultrasound the clinician must accurately identify the gallbladder and portal triad (common bile duct, portal vein, and hepatic artery). These structures are illustrated below

Source – https://radiologykey.com/hepatobiliary/

Source – http://www.em.emory.edu/ultrasound/Image

Risk/Benefits to Biliary Ultrasound

- Bedside ultrasound can be performed quickly and limits exposure to radiation

- Emergency physicians have good sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing biliary disease using point of care ultrasound (POCUS). A recent systematic review shows ED physicians to be 89.8% sensitive and 88.0% specific in diagnosing cholelithiasis (Ross 2011, PMID: 21401784). For cholecystitis recent literature states EM physicians are 87% sensitive and 82% specific using bedside ultrasound (Summers 2010, PMID: 20138397).

- Bedside ultrasound can be quickly used to either narrow a differential diagnosis – for example in a patient presenting with fever and abdominal tenderness – or to evaluate biliary structures in a patient with clinical suspicion for biliary disease

Common Indications

- Right upper quadrant pain

- Fever

- Nausea

- Jaundice

- Vomiting

Technique

- Biliary POCUS evaluates for five components to determine the presence or absence of pathology

- Gallstones

- Gallbladder wall thickening

- Pericholecystic fluid

- Common bile duct (CBD) distension

- Sonographic Murphy sign

- There are three principal techniques used to visualize gallbladder pathology using POCUS. A low frequency transducer is needed to achieve adequate depth of imaging.

Generally, a curvilinear probe is preferred, although a phased array probe may also be used.

- Subcostal Sweep

- With the probe marker cranial (longitudinal orientation) sweep the probe along the subcostal margin

- Imaging may be improved by asking the patient to inhale deeply or to turn onto their left side in a left lateral decubitus position

- Additionally, a sonographic Murphy sign may be elicited with this technique

- X minus 7

- This approach is used to visualize the gallbladder through an intercostal window

- The probe is placed approximately seven centimeters lateral to the xiphoid process, with the probe oriented to maximize the window between rib spaces

- If the gallbladder is not identified, continue to move the probe laterally, while fanning through the liver parenchyma

- Flatten the Probe

- With the probe marker to the patient’s right and the probe aimed towards the patient’s right shoulder fan anterior to posterior to identify the gallbladder

- As with any organ it is important to visualize the gallbladder in two planes

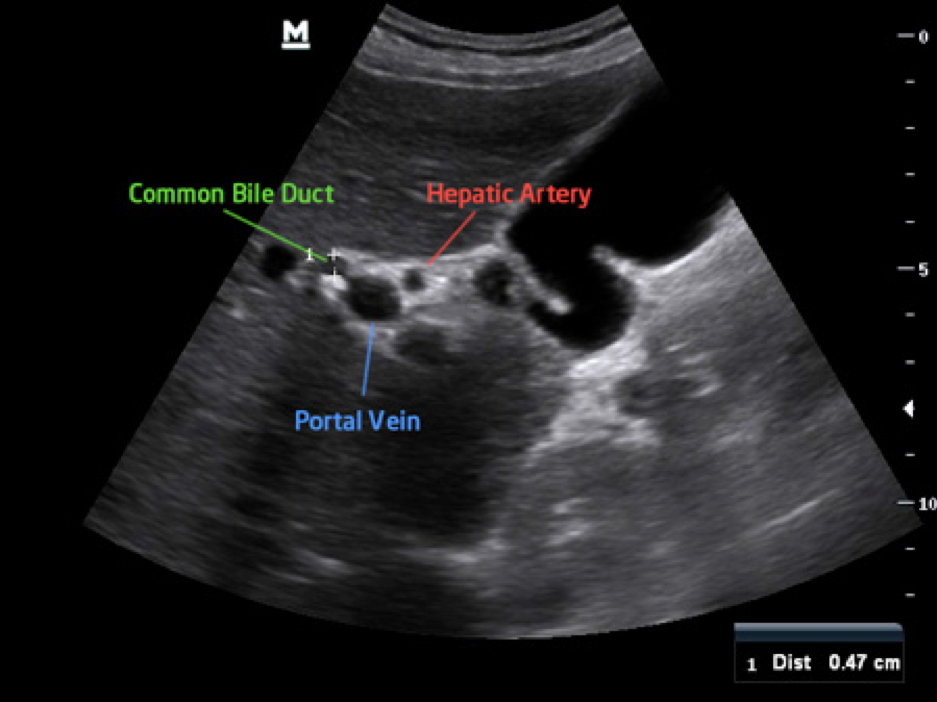

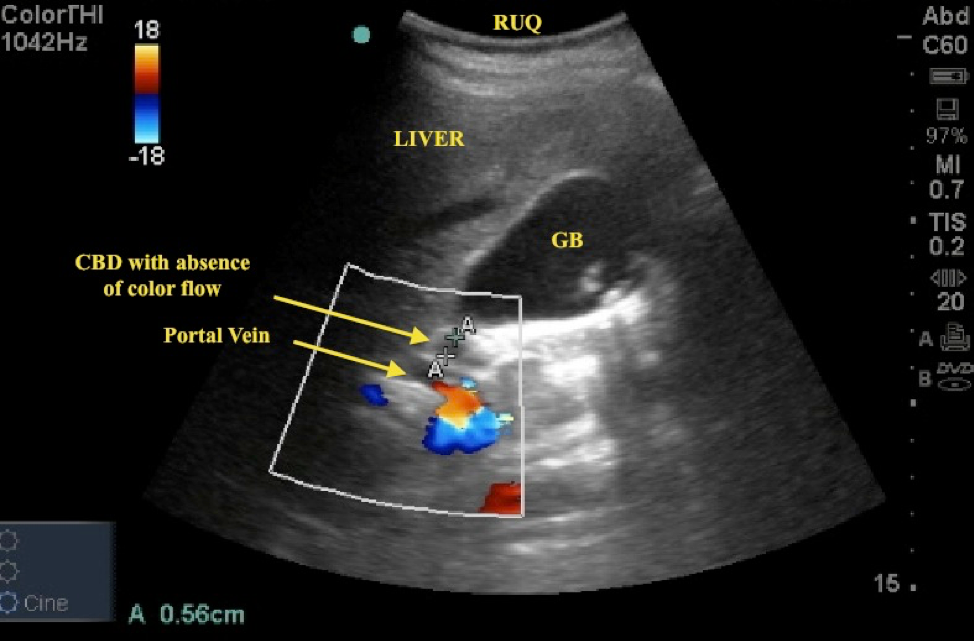

- Identifying portal vein, CBD and hepatic artery

- In a longitudinal view of the gallbladder, the portal triad is often viewed adjacent to the gallbladder, known as “Mickey Mouse” sign

Source – http://lluultrasound.org/home/ebook/abdo

-

- Note the neck of the gallbladder “folded” over on itself

- The main lobar fissure often runs from the neck of the gallbladder to the portal triad and may assist in identification

- Once identified, color doppler can be used to identify and differentiate the portal vein, hepatic artery, and CBD. The CBD will not demonstrate color flow

Source – http://www.em.emory.edu/ultrasound/Image

Evaluation

- Gallstones

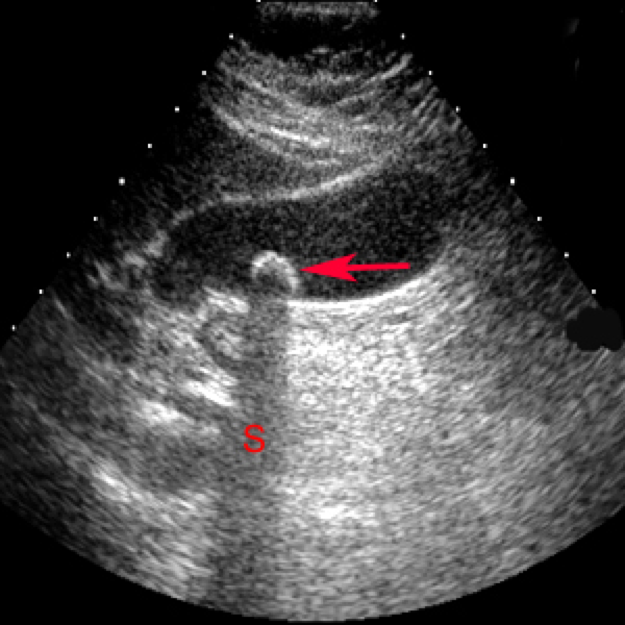

- Gallstones appear as hyperechoic structures in the gallbladder that also demonstrate shadowing

- If impacted in the neck of the gallbladder or CBD they can cause bile stasis and subsequent cholecystitis

- Gallstones that are not impacted may cause biliary colic that resolves spontaneously

- Repositioning the patient while visualizing gallstones allows a clinician to evaluate if stones are impacted or freely mobile

- Gallbladder sludge may be a precursor to gallstones and is sometimes associated with disease. Sludge appears as a dependent fluid with mixed echogenicity within the gallbladder.

Source – https://www.med-ed.virginia.edu/courses/

- Gallbladder Wall Thickening

- Gallbladder wall thickening is defined as greater than 3 millimeters and is often present in inflammatory process (Summers 2010, PMID: 20138397). Gallbladder wall thickening can be measured in the short or long axis and should be measured at the thickest point along the wall

- A number of normal states can also cause gallbladder wall thickening – including congestive states, ascites, and in the setting of a contracted gallbladder. Ultrasound findings must be interpreted in conjunction with clinical reasoning

- Pericholecystic fluid

- Pericholecystic fluid will appear as hypoechoic free fluid surrounding the gallbladder, often visualized in the space between the gallbladder and liver

- CBD distension

- Recent Emergency medicine literature defines the CBD as normally no greater than 6 millimeters (Becker 2014, PMID: 24126067; Lahham 2018, PMID: 29162442). Some literature will additionally add 1mm per decade of life over the age of 60 (Lahham 2018, PMID: 29162442)

- Post-cholecystectomy the CBD can measure up to 1 centimeter normally

- Sonographic Murphy Sign

- This finding is positive if the point of maximal tenderness in the right upper quadrant is identified while the gallbladder is visualized on ultrasound

5 Minute Sono Video

- Failure to visualize the neck of the gallbladder may result in missing pathology such as obstructing stones

- Inability to locate the CBD

- The CBD may be difficult to visualize on ultrasound and is often the most difficult part of the study for novice ultrasonographers. Tips for visualizing the CBD include using color doppler, following the main lobar fissure to the portal triad, and examining the gallbladder in multiple windows. If the patient is capable, repositioning may improve visualization

- Contracted Gallbladder

- A contracted gallbladder may be difficult to visualize and have walls that appear thickened with a three-layer appearance. If three layers are visible, this is not considered pathologic thickening

Source – http://www.ultrasoundcases.info/files/Jp

- Misidentification of the gallbladder

- The duodenum, a hepatic cyst, or a renal cyst may be misidentified as the gallbladder. It is important to examine any structures in their entirety and identify surrounding anatomy

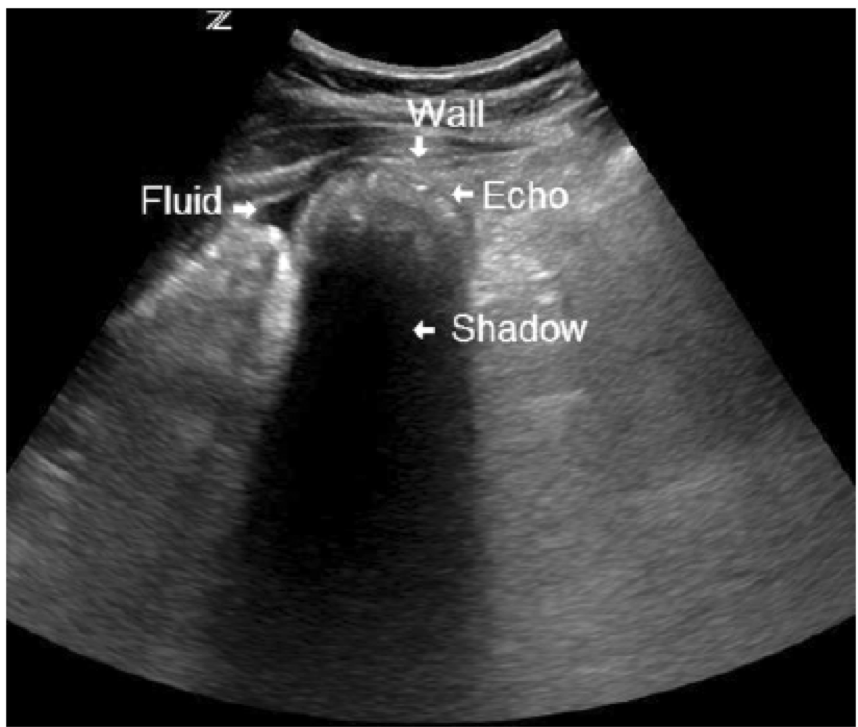

- Wall-Echo-Shadow sign (WES sign)

- This ultrasonographic sign occurs when the gallbladder is contracted around a stone or collection of stones. As a result, the shadowing from the stone(s) obscures the gallbladder posterior to the stone(s). Thus, the anterior gallbladder wall is visualized, followed by the hyperechoic stone(s), and then the stone(s) shadow

Source – https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Osa

- Gallbladder polyps can be confused with gallstones. Polyps demonstrate no shadowing and are not mobile. However, polyps in the neck of the gallbladder may potentially result in obstruction

Take Home Points

- POCUS performed by emergency medicine physicians has proven to be effective in detecting choledocholithiasis and cholecystitis and may reduce patient length of stay

- Biliary ultrasound should be performed with a low frequency transducer, using the subcostal sweep, X-7, or flatten the probe technique(s)

- Four major anatomic structures should be identified

- Gallbladder

- Hepatic artery

- Portal vein

- CBD

- Five components must be evaluated for the presence or absence of pathology in biliary ultrasound

- Gallstones

- Gallbladder wall thickening

- Pericholecystic fluid

- CBD distension

- Sonographic Murphy sign

- Common pitfalls generally include failure/misidentification all relevant anatomy or failure to differentiate between normal physiologic changes to the gallbladder and pathologic changes

References

Becker, B. A., E. Chin, E. Mervis, C. L. Anderson, M. H. Oshita and J. C. Fox (2014). “Emergency biliary sonography: utility of common bile duct measurement in the diagnosis of cholecystitis and choledocholithiasis.” J Emerg Med 46(1): 54-60. PMID: 24126067

Blaivas, M., R. A. Harwood and M. J. Lambert (1999). “Decreasing length of stay with emergency ultrasound examination of the gallbladder.” Acad Emerg Med 6(10): 1020-1023. PMID: 10530660

Cervellin, G., R. Mora, A. Ticinesi, T. Meschi, I. Comelli, F. Catena and G. Lippi (2016). “Epidemiology and outcomes of acute abdominal pain in a large urban Emergency Department: retrospective analysis of 5,340 cases.” Ann Transl Med 4(19): 362. PMID: 27826565

Lahham, S., B. A. Becker, A. Gari, S. Bunch, M. Alvarado, C. L. Anderson, E. Viquez, S. C. Spann and J. C. Fox (2018). “Utility of common bile duct measurement in ED point of care ultrasound: A prospective study.” Am J Emerg Med 36(6): 962-966. PMID: 29162442

Miettinen, P., P. Pasanen, J. Lahtinen and E. Alhava (1996). “Acute abdominal pain in adults.” Ann Chir Gynaecol 85(1): 5-9. PMID: 8739926

Ross, M., M. Brown, K. McLaughlin, P. Atkinson, J. Thompson, S. Powelson, S. Clark and E. Lang (2011). “Emergency physician-performed ultrasound to diagnose cholelithiasis: a systematic review.” Acad Emerg Med 18(3): 227-235. PMID: 21401784

Summers, S. M., W. Scruggs, M. D. Menchine, S. Lahham, C. Anderson, O. Amr, S. Lotfipour, S. S. Cusick and J. C. Fox (2010). “A prospective evaluation of emergency department bedside ultrasonography for the detection of acute cholecystitis.” Ann Emerg Med 56(2): 114-122. PMID: 20138397

Dear Alex, for the Mickey-sign, image orientation needs to be transverse plane (right ear is CBD, so right – left orientation), with gallbladder right in the patient (and not caudal, as in a sagittal orientation). In case a sagittal plane is used, the CBD is no longer on the “right” side. Both examples are therefore not correct, as the CBD is not positioned at the gallbladder side. Regards, Geert Plug, teacher in ultrasonography in the Netherlands.

Thank you for sharing valuable information