Definition: Acute, idiopathic peripheral facial nerve (CN VII) palsy

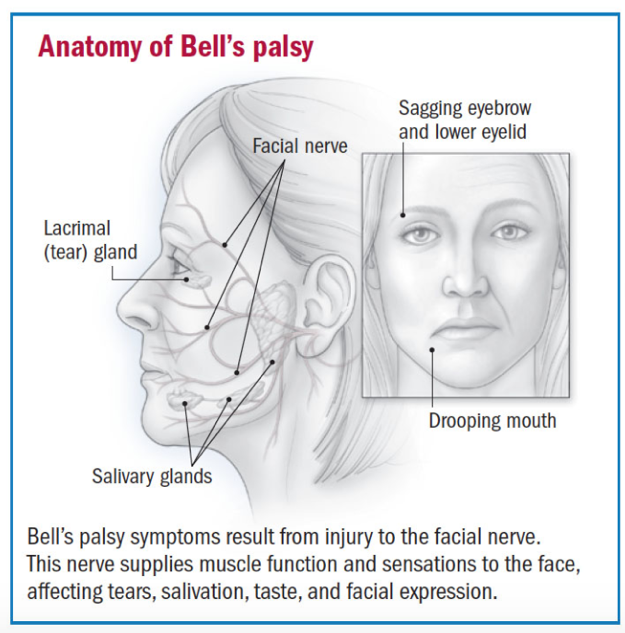

The Facial Nerve (CN VII):

- Provides parasympathetic innervation to the submandibular salivary glands, sublingual salivary glands, and lacrimal glands

- Conveys taste sensations from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue via sensory fibers

- Controls the muscles of facial expression

- Pearls:

- The right facial nerve controls the right face, and the left facial nerve controls the left face

- The upper muscles of facial expression are innervated by fibers from both the ipsilateral as well as contralateral cortex; in other words, innervation to each side of the forehead is from both motor cortices

- Therefore, a peripheral lesion should completely affect one side of the face, while a central lesion should spare the motor function of the forehead, since the contralateral cortex supplies fibers to the affected side

Etiology:

- Idiopathic by definition

- See differential for possible etiologies

- Mechanism: edema, inflammation, and nerve degeneration at the geniculate ganglion within stylomastoid foramen which can lead to compression and possible ischemia and demyelination

Epidemiology:

- Incidence of 15-40 / 100,000

- Affects men and women equally

- All ages are affected, with peak incidence in the 30s to 50s

- Risk factors include pregnancy, diabetes, and previous episode(s) of Bell’s palsy

History:

- Sudden onset unilateral facial droop, incomplete eyelid closure, and loss of forehead muscle tone

- Onset over the course of hours and peaks within three to seven days

- Facial asymmetry with disappearance of nasolabial fold and facial creases

- Eye irritation from decreased tearing and inability to close the affected eye

- Abnormal taste and drooling from the affected side

- Subjective “numbness” of the affected side due to paralysis but preserved facial sensation

Physical:

- Unilateral eyebrow sagging and inability to close the eye

- Disappearance of unilateral facial creases, especially nasolabial fold and forehead furrows

- Drooping at the corner of the mouth

- Although absolute tear production may be decreased, the inability to blink may allow tears to spill from the eye

- Preservation of the upper muscles of facial expression suggests a central cause

- Assess bilateral ear canals with otoscopy

- Assess parotid gland for masses

- Perform a full neurological exam: should expect an otherwise normal neurological exam including all other cranial nerves and extremity motor function

https://www.health.harvard.edu/pain/bells-palsy-overview

Differential:

- Bell’s palsy is a diagnosis of exclusion

- Herpes Zoster (Ramsay Hunt syndrome): evaluate for vesicles, tinnitus, or vertigo

- Infectious mononucleosis: evaluate for pharyngitis, posterior cervical adenopathy, or viral prodrome

- Guillain-Barré Syndrome: usually presents with ascending motor weakness

- Lyme Disease: history of rash or tick bite in endemic area

- Otitis Media

- Cholesteatoma

- Parotid gland masses

- Multiple Sclerosis: usually bilateral peripheral CN VII palsy

- Sarcoidosis: usually bilateral peripheral CN VII palsy

- Brainstem events (mass, bleed, infarct): will usually present with other cranial nerve palsies

- Basilar artery aneurysm

- Stroke

- Tumors: consider parotid, bone, metastatic masses, or acoustic neuroma

- Trauma: skull fracture or penetrating facial injury

Diagnosis:

- For high pre-test probability of Bell’s Palsy, there is no indication for labs or imaging: diagnosis is based on history and physical

- If you suspect another cause of facial nerve palsy, order targeted labs and/or imaging (e.g. Lyme titers or monospot if high suspicion for viral etiology)

- Consider blood glucose in Bell’s Palsy patients with other diabetic risk factors as 10% of Bell’s Palsy patients have diabetes

ED Management:

- Glucocorticoids may hasten recovery if started within 72 hours of symptom onset: 1mg/kg prednisone (or 60 to 80 mg) PO daily for 7 days (pediatric dose: 2mg/ kg/ day PO [max 60mg])

- NNT to prevent one incomplete recovery = 10

- No clear regimen, most studies use 7-10 days of PO prednisone

- Anti-viral therapy with steroids may improve functional nerve recovery if started within 72 hours of symptom onset: valacyclovir 1000 mg PO daily for 7 days (pediatric dose: 20mg/ kg TID PO)

- Low quality evidence that antivirals with glucocorticoids is superior to glucocorticoids alone

- American Academy of Neurology recommends offering antivirals while explaining limited evidence but also limited harm

- Corneal damage may occur due to incomplete eye closure

- prescribe lubricating and hydrating ophthalmic ointment and/ or drops (artificial tears qhs and prn dryness/ irritation in affected eye)

- instruct patient on wearing eye patch at night on affected eye

Prognosis:

- In the Copenhagen Facial Nerve Study (2002), 2,570 cases of untreated peripheral facial nerve palsy were studied during a period of 25 years (1,701 cases of Bell’s palsy)

- 71% of Bell’s palsy patients returned to baseline function in three weeks without treatment

- Almost all patients noticed some improvement in three to four months

- Prognosis is related to initial severity: with incomplete lesions, 94% returned to baseline whereas of those with complete lesions, 60% returned to baseline

Patient Education and Discharge Instructions:

- While not life threatening, Bell’s palsy can cause significant distress

- Symptoms peak within three to seven days, and almost always improve somewhat by 3 months

- With incomplete lesions, ~95% return to baseline; with complete lesions, ~60% return to baseline

- Prescribe artificial tears during the day and ointments with eye patch at night

- 1 week follow-up with outpatient neurologist for management of symptoms and to monitor recovery

Take Home Points:

- Bell’s palsy is acute, peripheral, and idiopathic

- A non-acute onset of symptoms (gradual onset of more than two weeks duration) should suggest a mass lesion

- Perform a very careful thorough exam, including full neurological exam, dermatological exam (evaluate for vesicles or rash), and ENT exam (evaluate for pharyngitis, posterior cervical adenopathy, otitis media, deafness)

- No role for labs or imaging, but deviation from the typical history and physical should prompt further workup

- Start glucocorticoids and antivirals in the ED if symptoms started within 72 hours and if there are no contraindications

- Provide patient education about the prognosis and eye care to prevent corneal abrasions

- Arrange for close neurology follow-up

References:

Zhang W, Xu L, Luo T, Wu F, Zhao B, Li X. The etiology of Bell’s palsy: a review. Journal of Neurology. 2019. doi:10.1007/s00415-019-09282-4.

Tiemstra JD, Khatkhate N. Bell’s Palsy: Diagnosis and Management. American Family Physician. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2007/1001/p997.html. Published October 1, 2007. Accessed May 22, 2019.

Gronseth GS, Paduga R. Evidence-based guideline update: Steroids and antivirals for Bell palsy: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2012;79(22):2209-2213. doi:10.1212/wnl.0b013e318275978c.

Madhok VB, Gagyor I, Daly F, et al. Corticosteroids for Bells palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001942.pub5.

Gagyor I, Madhok VB, Daly F, et al. Antiviral treatment for Bells palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001869.pub6.

Loomis C, Mullen MT. Differentiating Facial Weakness Caused by Bell’s Palsy vs. Acute Stroke. Journal of Emergency Medical Services. https://www.jems.com/articles/print/volume-39/issue-5/features/differentiating-facial-weakness-caused-b.html. Published May 7, 2014. Accessed May 22, 2019.

Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2002:4-30.

Schaider et al. Rosen & Barkin’s 5-Minute Emergency Medicine Consult, 5th Edition. Wolters Kluwer.