Introduction:

- Akathisia, derived from the Greek word meaning “inability to sit still”, is a common side effect of many anti-psychotic and anti-nausea medications. It describes an irrepressible feeling of restlessness, difficulty remaining seated or still, constant shifting of legs and pacing (Adler 1989). The condition can result in severe distress; patients have described a desire to crawl or jump out of their skin.

- Given the frequency with which “culprit” medications are given in the Emergency Department, akathisia should not be considered an uncomplicated adverse reaction. Instead, it is an urgent condition that has been associated with high-lethality suicide attempts (Drake 1985, Cheng 2013), homicide attempts (Leong 2003), and hospital elopement. Prompt diagnosis is essential to avoid exacerbating the condition with more antipsychotics.

Etiology and Classification:

- Recognized since the 1950s as a paradoxical increase in restlessness/agitation, akathisia most commonly results in response to first-generation antipsychotics such as haloperidol (Hodge 1959). It can present as an exacerbation of chronic medication use, or acutely in the ED.

- Acute Akathisia is most commonly seen in the ED as a side effect of drugs with D-2 receptor antagonism used to treat nausea or migraine:

- Prochlorperazine (Drotts 1999) – in up to 44% of patients treated with 10mg.

- Metoclopramide (Friedman 2009) – in up to 25% of patients treated with 10mg.

- Droperidol (Foster 1996).

- Chronic Akathisia describes one of four extra-pyramidal side effects (besides acute dystonia, Parkinsonism, and tardive dyskinesia) that is commonly associated with long term use of first > second generation antipsychotics (Peluso 2012).

- 1st generation: Haloperidol, fluphenazine, trifluoperazine, etc.

- 2nd generation: Risperidone, quetiapine, olanzapine, etc.

- It has also been associated with SSRIs and SSRI-associated-suicide (Lancon 1997).

Diagnosis;

- Akathisia is a clinical diagnosis with a validated metric for assessing severity and response to treatment (Barnes 1989, Barnes 2003). Watch for:

- Patient engaged in restless movements ± inability to remain seated / pacing.

- Awareness of compulsion for movement.

- Distress due to these symptoms.

- History and medication use (or abuse) is extremely important in this diagnosis.

- Examine pupils, skin, and bowel sounds to r/o anticholinergic toxicity.

- Check finger stick glucose, BMP, TSH.

- Check CBC w/diff, UA, CXR to evaluate for infection in elderly.

- Consider serum ETOH to rule out ethanol withdrawal and urine toxicology for sympathomimetics and to rule out benzodiazepine withdrawal.

- Restless legs syndrome is also a clinical diagnosis, and can be distinguished from akathisia by the presence of hypnogogic myoclonus of the legs, cramping of the legs at night, and always being associated with rest/sleep. (Silber 2019).

Differential Diagnosis:

- thyrotoxicosis

- sympathomimetic toxidrome

- anticholinergic toxidrome

- alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal

- restless leg syndrome

- hypoglycemia

- delirium in the elderly

- psychosis

- mania

- ADHD

- agitated depression

Management:

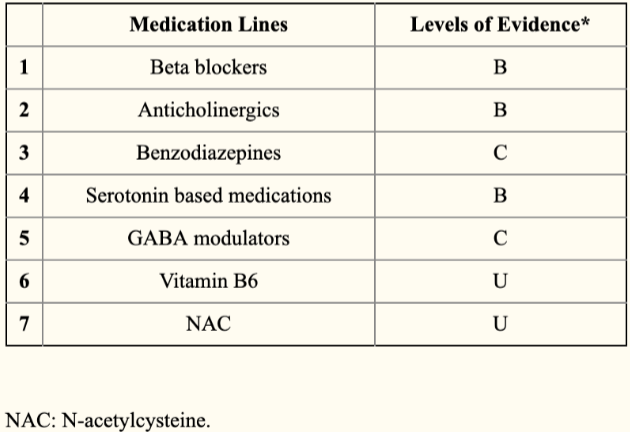

There are a variety of options recommended, with limited evidence distinguishing their efficacy. The most important action is to discontinue the offending agent and not further exacerbate the condition with more antipsychotics.

- Acute: Diphenhydramine and benzodiazepines both work quickly, but the latter are more sedating (Parlak 2007). If considering diphenhydramine or benztropine, beware of anticholinergic toxicity presenting as agitation/akathisia.

-

- Midazolam 2mg-5mg IM/IV.

- Diphenhydramine 50-100mg IV.

- Benztropine 1-2mg IV.

- AVOID haloperidol!

-

- Chronic: Propranolol (Lipinksi 1984), mirtazapine (Poyurovsky 2006), benztropine (Adler 1993), and cyproheptadine (Fischel 2001) have all been shown effective in treating chronic akathisia. These options generally show an effect in 3 days or less. The evidence showing superiority of one option over others is unclear, and side effect profiles take precedence.

-

-

- Propranolol 10-30mg PO TID is often considered first line unless there are concerns for bradycardia, hypotension, or asthma.

- Mirtazipine at low dosing – 15mg QD – has been shown to be effective, but high doses may actually worsen akathisia (Gulsun 2008).

- Benztropine 6mg QD has been shown to work as well, but may cause confusion and urinary retention.

- Cyproheptadine 16mg QD has also been shown effective.

- AVOID antipsychotics!

-

-

Prevention/ Prophylaxis:

- Avoid drugs with D2 receptor antagonism if the patient has a history of akathisia, e.g. use ondansetron instead of prochlorperazine for nausea.

- Prophylaxing with diphenhydramine has been shown to decrease akathisia when giving prochlorperazine (Vinson 2004) or when giving a dosage of 20mg of metoclopramide (Friedman 2009).

- Slowing the infusion rate of metoclopramide also decreases the risk of akathisia (Parlak 2005).

Disposition:

- If a patient expresses SI/HI, or is considered at risk, hospitalization or 1-to-1 observation may be necessary.

- The patient may otherwise be discharged home with primary care follow-up, or psychiatric outpatient follow-up, if needed. Patients with chronic akathisia may be started on daily medication.

Take -Home Points:

- Consider chronic akathisia in the anxious patient, especially those with a complicated psychiatric medication history, and avoid exacerbating with further antipsychotics.

- Avoid acute akathisia by prophylaxing with diphenhydramine before treating with anti-nausea or anti-migraine medications with D2-receptor antagonism, and slowing the rate of metoclopramide infusion.

References:

Adler L, Angrist B, Reiter S, Rotrosen J. Neuroleptic-induced akathisia: a review. Psychopharmacology 1989;97(1):1-11. PMID: 2565586.

Drake R, Ehrlich J. Suicide attempts associated with akathisia. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(4):499-501. PMID: 3976927.

Cheng H, Park J, Hernstadt D. Akathisia: a life-threatening side effect of a common medication. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 (May 21). PMID: 23697447.

Leong G and Silva J. Neuroleptic-induced akathisia and violence. J Forensic Sci. 2003;48(1):187-189. PMID: 12570226.

Braude D, Boling S. Case report of unrecognized akathisia resulting in an emergency landing and RSI during air medical transport. Air Med J. 2006;25(2):85-7. PMID: 16516120.

Hodge J. Akathisia: The syndrome of motor restlessness. Am J Psychiatry, 1959;116:337-8. PMID: 14402223.

Drotts D, Vinson D. Prochlorperazine induces akathisia in emergency patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1999; 34(4):469-75. PMID: 10499947.

Friedman B, Bender B, Davitt M, et al. A randomized trial of diphenhydramine as prophylaxis against metoclopramide-induced akathisia in nauseated emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(3):379-85. PMID: 18814935.

Foster P, Stickle B, Laurence A. Akathisia following low-dose droperidol for antiemesis in day-case patients. Anaesthesia. 1996;51(5):491-4. PMID: 8694168.

Peluso M, Lewis S, Barnes T, and Jones P. Extrapyramidal motor side-effects of first and second generation antipsychotic drugs. Brit J Psych. 2012;200(5):387-92. PMID: 22442101.

Lancon C, Bernard D, Bougerol T. Fluoxetine, akathisia, and suicide. L’Encephale. 1997;23(3):218-23. PMID: 9333553.

Barnes T. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. British J Psych. 1989;154:672-6. PMID: 2574607.

Barnes T. The Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale – Revisited. J Psychopharm. 2003;17(4):365-370. PMID: 14870947.

Silber M, Hurtig H, Avidan A, Eichler A. Treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in adults. UpToDate. June 2019.

Parlak I, Erdur B, Parlak M, et al. Midazolam vs diphenhydramine for the treatment of metoclopramide-induced akathisia: a randomized controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(8):715-21. PMID: 17545174.

Lipinski J, Zubenko G, Cohen B, Barreira P. Propranolol in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Am J of Psychiatry, 1984; 141(3):412-415. PMID: 6142657.

Poyurovsky M, Pashinian A, Weizman R, et al. Low-dose mirtazapine: a new option in the treatment of antipsychotic-induced akathisia. A randomized, double-blind, placebo- and propranolol-controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2006; 59(11):1071-7. PMID: 16497273.

Adler L, Peselow E, Rosenthal M, Angrist B. A controlled comparison of the effect of propranolol, benztropine, and placebo on akathisia: an interim analysis. Psychoparmacol Bull. 1993;29(2):283-6. PMID: 8290678.

Fischel T, Hermesh H, Aizenberg D, et al. Cyproheptadine versus propranolol for the treatment of acute neuroleptic-induced akathisia: a comparative double-blind study. J Clin Psychopharm. 2001;21(6):612-5. PMID: 11763011.

Gulsun M and Doruk A. Mirtazapine-Induced Akathisia. J Clin Psychopharm. 2008;28(4):467. PMID: 18626283.

Salem H, Nagpal C, Pigott T, Teizeira A. Revisiting Antipsychotic-induced akathisia: current issues and prospective challenges. Curr Neuropharmacol 2017;15(5):789-798. PMID: 27928948.

Vinson D. Diphenhydramine in the treatment of akathisia induced by prochlorperazine. J Emerg Med. 2004;26(3):265-70. PMID: 15028322.

Parlak I, Atilla R, Cicek M, et al. Rate of metoclopramide infusion affects the severity and incidence of akathisia. Emerg Med J. 2005;22(9)621-4. PMID: 16113179.

Image: 1: Gino Severini, La Danse Macabre, 1912. (From https://www.flickr.com/photos/rmh40/8024672340 under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC 2.0), cropped and brightened.)