Air Embolism (safeinfusiontherapy.com)

Definition: Entrainment of air into the venous or arterial system as a result of direct communication and a pressure gradient. Venous air can enter from blunt or penetrating trauma, central venous catheter manipulation, intravenous contrast injections, and surgery (e.g., ophthalmologic, neurosurgical, dental procedures and cesarean delivery) (O’Dowd 2013).

- Moderate to large air emboli are medical emergencies that require rapid diagnosis and treatment to prevent disability and death.

- Dog model: 0.5 mL/kg/min led to cardiorespiratory failure (Adornato 1978)

- Human data: 200-500 mL air introduced at 100 mL/sec was acutely fatal (~3–5 mL/kg), other estimates suggest < 50 mL of air (O’Dowd 2013, Feil 2015)

Epidemiology

- Central lines are the most common source in the Emergency Department. Incidence: 1/40 to 1/3000 central lines (Feil 2015)

- Unknown in peripheral lines

- In one study researchers inserted 18 or 20 gauge IVs into upper extremity veins in 208 individuals scheduled for non-con CT chest. 4.8% of patients had small, clinically insignificant air emboli: 6 in the pulmonary trunk, 2 in the right ventricle, 1 in the right atrium (Groell 1997)

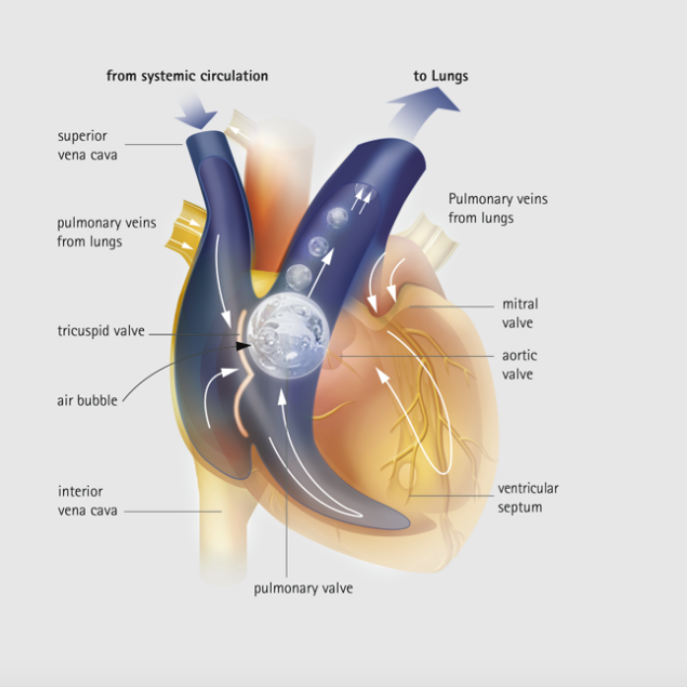

Pathophysiology

- Hypovolemia may create a sub-atmospheric pressure gradient within the venous system, allowing for higher pressure air to travel towards the veins

- Venous air travels from the right heart into the pulmonary system, diffuses across the arteriolar wall into the alveolar space

- When air > 50 mL, the remainder can obstruct the right ventricular outflow tract

- Large bubbles (“air locks”) will decrease flow from right heart

- Smaller bubbles become wedged within pulmonary arterioles, microcirculation, coronary vessels, inhibit forward flow and cause vasoconstriction, myocardial ischemia (O’Dowd 2013)

Presentation

- Variable, nonspecific presentation (Campbell 2014)

- Frequently encountered symptoms: dizziness, dyspnea, substernal chest pain, elevated JVP,

- Frequently encoutered findings: hypoxia, churning mill wheel murmur, unexplained hypotension or hemodynamic collapse, loss of consciousness

CT Chest Showing Air Embolism

Diagnostic Modalities

- EKG: sinus tachycardia, right heart strain, T wave changes (non-sensitive, non-specific)

- End tidal CO2: unexplained decrease of 2 mmHg can indicate VAE (non-specific)

- Chest X-ray or CT Chest: air in pulmonary artery or pulmonary artery enlargement (non-sensitive but highly specific)

- Transthoracic echocardiography may demonstrate intra-cardiac air. Transesophageal echo is the most sensitive monitoring device for venous air embolism, but is rarely available (O’Dowd 2013)

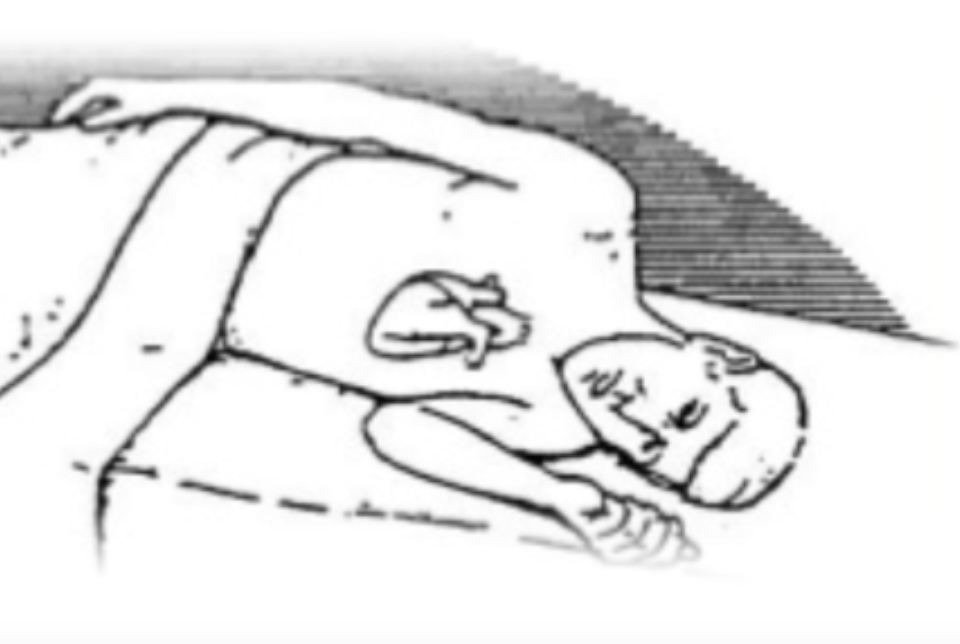

Durant’s Maneuver

Management

- High-flow, 100% oxygen

- Left lateral decubitus position (Durant’s maneuver) and/or Trendelenburg position if hemodynamically unstable

- Cardiovascular collapse and arrest should be managed in standard fashion

- Hemodynamic support: IV fluids, inotropes, and vasopressors

- Rapid initation of CPR with high-quality chest compressions

- Mechanical removal/air aspiration from existing central line (if in place)

- Consider emergent cardiopulmonary bypass

- Hyperbaric oxygen (Adornato 1978, Alvaran 1987)

- Hyperbaric oxygen ncreases the partial pressure of oxygen and decrease the partial pressure of nitrogen in the blood

- Theoretically, this causes nitrogen from inside the emboli to diffuse into the blood and reduce the bubble size

Take Home Points

- Air embolism is a rare but potentially fatal complication of central line placement and specific surgical procedures

- Recognition can be difficult as initial signs and symptoms are non-specific. Consider the diagnosis in any patient with decompensation after placement of a central line

- Treatment should focus on supportive care, air embolism aspiration when feasible and consultation for hyperbaric and cardiopulmonary bypass

References

Adornato DC et al. Pathophysiology of intravenous air embolism in dogs. Anesthesiology. 1978;49:120-7. PMID: 686416

Alvaran SB et al. Venous air embolism: comparative merits of external cardiac massage, intracardiac aspiration, and left lateral decubitus position. Anesth Analg. 1978;57:166-70. PMID: 565152

Campbell, J. Recognising air embolism as a complication of vascular access. Br J Nurs. 2014;23 Suppl 14:S4-8. PMID: 25158360

Feil M. Preventing central line air embolism. Am. J. Nurs. 2015;115:64–69. PMID: 26018011

Groell R et al. The peripheral intravenous cannula: a cause of venous air embolism. Am J Med Sci 1997;314:300–2. PMID: 9365331

O’Dowd LC, Kelley MA. Air embolism. UpToDate 2013. LINK

Hi,

arterial gas embolisation also occurs as a rare complication to lung biopsies. (but not THAT rare)

Air enters pulmonary veins and direct cerebral arterial embolisation results in more classical pattern of stroke symptoms

Patient should then be placed in right lateral decubitus and trendelenburg position in order to trap bubbles in the trabeculae of the left ventricle (not Durants maneuver)

There are few other causes of direct arterial gas embolization — i.e. CPBP — though this is probably the most common.

Hyperbaric therapy also directly and immediately reduces bubble size (Boyle´s law) in addition to the mechanisms mentioned.