The Case

CC

Abnormal lab values

HPI

68 yo F sent to ED by PMD for abnormal lab values. Patient states she had a prolonged episode of epistaxis lasting about one hour 7 days ago and subsequently developed exertional dyspnea and increased lower extremity swelling. Patient endorses decreased exercise tolerance and is unable to walk more than one block now. Patient states she was unable to sleep last night as she was unable to laydown due to difficulty breathing. Patient denies chest pain, melena, bright-red-blood-per-rectum. Patient states she had taken furosemide in the past, but was stopped due to kidney injury from concurrently taking gout medication. Patient saw her PMD yesterday, had labs drawn and was prescribed furosemide again, but states she has not yet started taking it.

Patient also states she noted her blood pressure to be intermittently very low with sBP in 70s 3 days ago. Patient also feels her blood pressure is less than it normally is today. States her sBP is usually 160-170s.

PMH / PSH

PMH: CHFpEF (baseline EF 56%), hypertension, gout

Medications: nebivolol, clonidine, quinapril, colchicine, vitamin D

PSH: None

ALL: NKDA

ROS

+Shortness of breath, Lower extremity edema, otherwise negative

Physical Exam

PE: Exam limited by habitus

Tc 36.9 HR83 RR20 BP140/85 O2Sat 96% RA

GEN: NAD, AOx3, elderly obese woman, speaking in full sentences

HEENT: Atraumatic, Normocephalic, EOMI, PERRL, +JVD

COR: +s1, s2, Regular rate and rhythm, no distinct murmurs

PULM: CTA b/l

ABD: Obese, Soft, non-tender

Extr: WWP, +1 pitting edema b/l up to knees

Neuro: CNII-XII grossly intact

Labs

CBC: 6.7 > 9.7/29.6 < 350 (baseline H/H from 5 months ago 12.8/40.5)

BMP: 132 | 96 | 18 < 101

5 | 26 | 0.8

BNP: 5090

Troponin: Negative

Media

Questions

-

We then did a diagnostic test that revealed the diagnosis. What was the test and the diagnosis?

A bedside echo was performed showing a large pericardial effusion consistent with tamponade physiology.

Cardiology and electrophysiology were consulted and a formal bedside echo was obtained confirming tamponade. Given the relative stability of the patient’s blood pressure, the patient was emergently transferred to the OR for pericardiocentesis instead of opting for bedside pericardiocentesis. One liter of bloody fluid was drained from the pericardium and a pigtail was left in place. Pericardial fluid was sent for a myriad of tests including rheumatologic panel, cytology, TB, culture with no diagnostic yield. Etiology of the inciting event remains elusive. Patient is currently stable with no recurrent pericardial effusion

More Info

Point-of-care ultrasonography has become an integral tool for emergency physicians to assess patients in extremis, especially when classic physical exam findings such as Beck’s triad of JVD, muffled heart sounds and hypotension are rarely present3,8,11. However, most patients with tamponade will manifest either frank or relative hypotension7. So when evaluating patients with a decreased blood pressure, tamponade should always be part of the differential.

Bedside echocardiography for the evaluation of pericardial effusion has been accepted in the scope of practice for emergency physicians and is supported by ACEP (American College of Emergency Physicians) and ASE (American Society of Echocardiography)3,11. Bedside echocardiography becomes especially helpful in the undifferentiated dyspneic patient as up to 10% of patients with undifferentiated dyspnea in the Emergency Department have been found to have underlying pericardial effusions2.

In cardiac tamponade, increased pressure in the pericardial sac from accumulation of fluid deters the lower pressure system of the heart to fill during diastole causing eventual right atrial and ventricular collapse. The earliest and most sensitive sign of cardiac tamponade is right atrial collapse4. Right ventricular collapse is very specific for tamponade physiology, but less sensitive11. A plethoric IVC with no respiratory variation can also be found in tamponade though this is non-specific and can occur in other conditions with elevated right heart pressure. Importantly, if the patient has chronic pulmonary hypertension with chronically elevated right heart pressures, right atrial or ventricular collapse may only be a very late manifestation11.

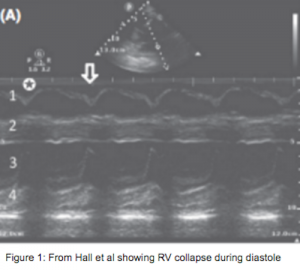

To differentiate between diastolic collapse and normal systolic movement of the right ventricular free wall, one can view the heart in parasternal long view using M-mode with the axis through both the right ventricular free wall and the mitral valve1-2,6,11. In tamponade, the right ventricular free wall paradoxically moves inwards toward the septum as the mitral valve opens (Figure 1).

To differentiate between diastolic collapse and normal systolic movement of the right ventricular free wall, one can view the heart in parasternal long view using M-mode with the axis through both the right ventricular free wall and the mitral valve1-2,6,11. In tamponade, the right ventricular free wall paradoxically moves inwards toward the septum as the mitral valve opens (Figure 1).

Sonographic pulsus paradoxus can be documented in the apical-four chamber view with pulsed-wave Doppler. Paradoxical decrease in velocity of blood flow through the mitral valve greater than 25% during inspiration will be seen in tamponade physiology1-2 (Figure 2).

Sonographic pulsus paradoxus can be documented in the apical-four chamber view with pulsed-wave Doppler. Paradoxical decrease in velocity of blood flow through the mitral valve greater than 25% during inspiration will be seen in tamponade physiology1-2 (Figure 2).

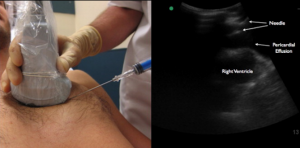

Pericardiocentesis has been performed to relieve tamponade since the 18th century, but without visualization of the effusion, blind Pericardiocentesis has historically had an unacceptable rate of morbidity up to 50% and mortality of 6%10. Since the advent of ultrasound in the 1970s, ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis has become the standard-of-care, significantly reducing morbidity and mortality9-10. A retrospective review from the Mayo Clinic of 21 years of ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis found a 97% overall success rate and a complication rate of 4.7%9.

In 2013, Nagdev et al published a step-by-step protocol demonstrating an in-plane approach allowing the user to visualize the needle as it approaches the pericardium6. With the ultrasound screen on the patient’s right side, the operator stands on the patient’s left side6. The operator obtains the parasternal long view and the needle is inserted in plane while the ultrasound probe is maintained on the patient’s chest with real time visualization of the needle insertion into the pericardium5.

In 2013, Nagdev et al published a step-by-step protocol demonstrating an in-plane approach allowing the user to visualize the needle as it approaches the pericardium6. With the ultrasound screen on the patient’s right side, the operator stands on the patient’s left side6. The operator obtains the parasternal long view and the needle is inserted in plane while the ultrasound probe is maintained on the patient’s chest with real time visualization of the needle insertion into the pericardium5.

References:

- Chandraratna PA, Mohar DS, Sidarous PF, Role of echocardiography in the treatment of cardiac tamponade. Echocardiography, 2014 Aug;31(7):899-910.

- Hall KM, Coffey EC, Herbst M, Liu R, Pare JR, Taylor AR, Thomas S, Moore CL, The “5Es” of emergency physician-performed focused cardiac ultrasound: a protocol for rapid identification of effusion, ejection, equality, exist and entrance. Acad Emerg Med, 2015 May;22(5):583-93.

- Labovitz AJ, Noble VE, Bierig M, Goldstein SA, Jones R, Kort S, Porter TR, Spencer KT, Tayal VS, Wei K, Focused cardiac ultrasound in the emergent setting: a consensus statement of the American society of echocardiography and American college of Emergency Physicians. J Am Soc Echocardiogr, 2010 Dec;23(12):1225-30.

- Materazzo C, Piotti P, Meazza R, Pellegrini MP, Viggiano V, Biasi S, Respiratory changes in transvalvular flow velocities versus two-dimensional echocardiographic findings in the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade. Ital Heart J, 2003 Mar;4(3):186-92.

- Nagdev A, Mantuani D, A novel in-plane technique for ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis. Am J Emerg Med, 2013 Sep;31(9):1424.e5-9.

- Perera P, Lobo V, Williams SR, Gharahbaghian L, Cardiac echocardiography. Crit Care Clin, 2014 Jan;30(1):47-92.

- Spodick DH, Acute cardiac tamponade. N Engl J Med, 2003 Aug;349(7):684-90.

- Tang A, Euerle B, Emergency department ultrasound and echocardiography. Emerg Med Clin North Am, 2005 Nov;23(4):1179-94.

- Tsang TS, Enriquez-Sarano M, Freeman WK, Barnes ME, Sinak LJ, Gersh BJ, Bailey KR, Seward JB, Consecutive 1127 therapeutic echocardiographically guided pericardiocenteses: clinical profile, practice patterns, and outcomes spanning 21 years. Mayo Clin Proc, 2002 May;77(5):429-36.

- Tsang TS, Freeman WK, Sinak LJ, Seward JB, Echocardiographically guided pericardiocentesis: evolution and state-of-the-art technique. Mayo Clin Proc, 1998 Jul;73(7):647-52.

- Weekes AJ, Quirke DP, Emergency echocardiography. Emerg Med Clin North Am, 2011 Nov;29(4):759-87.

An echo-the patient may have an acute mitral regurgitation (perhaps from myocardial ischemia…there are a few t wave abnormalities in the lateral leads of the EKG) causing flash pulmonary edema and the irregular rhythm on the EKG (mitral regurgitation leads to dilation of the left atrium causing atrial fibrillation due to stretching of the myocardium).