Definition:

- “An episode that is frightening to the observer and that is characterized by some combination of apnea (central or obstructive), color change (usually cyanotic or pallid but occasionally erythematous or plethoric), marked change in muscle tone (usually implies limpness), choking, or gagging. In some cases, the observer fears the infant has died.” (NIH Consensus Statement 1986)

- Established to replace misleading terms such as “near SIDS” as there is no causal relationship between ALTE and SIDS

Epidemiology:

- 05% to 1.0% of infants

- 6% to 0.8% of all ED visits per year in children under 1 year of age (McGovern 2004)

- Recurrence rate of 10-25%

- Risk of subsequent death is 0%-6%

- ALTE requiring CPR have 10-30% chance of subsequent SIDS (Oren 1986)

- ALTE usually occurs in the first 2 months of life

Predisposing factors:

- Risk factors: (Kiechl-Kohlendorfer 2005)

- History of ALTE

- Maternal smoking during pregnancy

- Feeding difficulties

- Suspected seizures

- Respiratory infection

- Suspected non-accidental trauma.

- Questionable risk factors:

- Male sex

- Prematurity

Causes

- Etiology only found in about 50% of cases

- Frequency of identified causes: (McGovern 2004)

- GERD/Choking/Laryngospasm (31%)

- Seizure (11%)

- Respiratory infection (8%)

- ENT infection (3.6%)

- Errors in Metabolism (1.5%)

- Toxins (1.5%)

- UTI (1%)

- Cardiac (1%)

- Non-accidental trauma (1%)

- Mechanisms:

- GERD:

- Unclear connection/causality. GERD diagnosed in 30% of ALTE patients, but common in all infants.

- Difficult to differentiate between inadequate airway protection allowing for microaspirations vs over-active airway reflexes responding to minor regurgitation with laryngospasm. (Orenstein 2001)

- Respiratory infection:

- Usually lower respiratory infection, especially RSV and Pertussis.

- Non-accidental trauma:

- Often intentional suffocation, non-accidental head injury, and intentional poisoning.

- Suspect if the history does not match the symptoms, if the story is inconsistent, or with physical exam findings such as facial bruising, bulging fontanelle, or retinal hemorrhage.

- In one series, 1/3 of ALTE cases requiring CPR were caused by intentional suffocation (Southall 1997)

- GERD:

Presentation:

- The patient usually appears well at the time of presentation.

- Note that healthy infants can have respiratory pauses as long as 30 seconds and bradycardia for 10 seconds during sleep without any harm.

Diagnostics + Management:

- Basics

- Assess for stability. If unstable, follow standard resuscitation.

- Look for and treat potential infectious causes.

- Screen for RSV and pertussis if suspected respiratory infection

- Comprehensive History: including previous events, recent illness, infant’s usual behavior, sleeping and eating habits, family/sibling history, social history including tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs, and medications in the house. Ask specifically about cold medications as they are common and many parents will not perceive the presence or administration of these over-the-counter medications as pertinent.

- Suspected GERD:

- Try thickening feeds, trial of milk-free diet, prone positioning.

- Prokinetic and acid suppressing therapies are widely used, but have little evidence supporting, and are not approved by US FDA for this purpose.

- If recurrent, or infant has neurologic or developmental disorder then swallowing study may be indicated. (Orenstein 2001)

- Suspected Seizure:

- EEG usually normal and have low clinical yield

- Suspected Non-accidental Trauma:

- Follow up with radiographic survey, neuroimaging, fundoscopic exam, and social work screening.

- Suspected GERD:

- Laboratory investigations

- Typically unhelpful

- Order labs if working up a patient who appears ill in the ED, or if history and physical favor a certain diagnosis that can be elucidated with targeted labs. (Brand 2005)

- Polysomnography and home cardiorespiratory monitoring

- Low yield in predicting future ALTE or SIDS.

- Pose potential uncertainties and stress on parents. However some relative indications include prematurity, recurrent apnea, bradycardia, unstable airways, chronic lung disease (American 2005)

Disposition:

- In the past, most ALTE infants were admitted for observation, however interventions required during admission were infrequent.

- Clinical gestalt alone is 96% sensitive and 24% specific for identifying patients that required intervention. (Kaji 2013)

- 2 major studies exist to help reduce hospital admissions (increase specificity) without missing cases that would have benefitted from intervention (keeping sensitivity high)

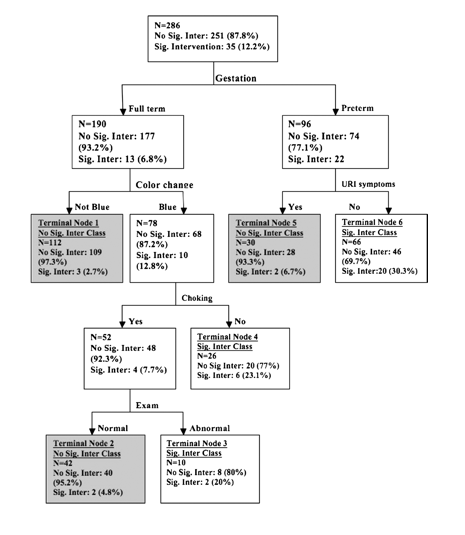

- Mittal MK et al A clinical decision rule to identify infants with apparent life-threatening event who can be safely discharged from the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2012; 28(7): 599-605. PMID: 22743742

- Single Center

- 300 infants enrolled, 76% admitted, 12% required significant intervention.

- Inclusion: under 1 year old, +ALTE dx.

- Exclusion: clear evidence of disease at ED presentation.

- Primary outcome

- Return visit to ED within 72hrs

- Requirement of significant intervention during hospitalization (including antibiotics, anti-epileptics, supplemental oxygen, suctioning, intubation, and echocardiography).

- Decision Instrument – okay to discharge home if:

- Premature with URI symptoms

- Full-term with non-cyanotic color change

- Full-term with cyanotic color change and history of choking during episode

- If implemented, these rules would reduce hospital admission rate to 36% (40% reduction), with NPV 96.2%. It missed 3.8% of patients

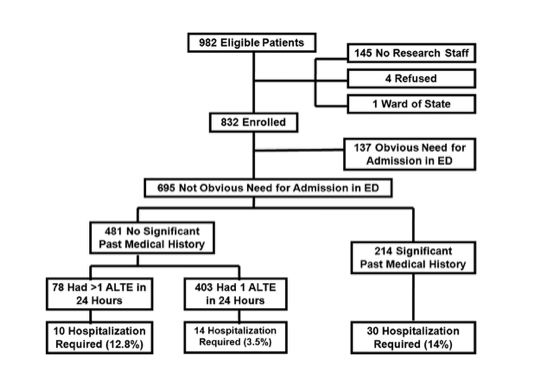

- Kaji AH et al. Apparent life-threatening event: multi center prospective cohort study to develop a clinical decision rule for admission to the hospital. Ann Emerg Med 2013; 61(4): 379-87. PMID: 23026786

- Multiple centers in Philadelphia and Los Angeles, including academic and community EDs

- 832 subjects enrolled

- Inclusion episode that meets at least 2 of the ALTE conference consensus definitions.

- Exclusion: ALTE in hospital, hypoxia<92%, seizure, systemic bacterial infection, +RSV, +pertussis, arrhythmia, concern for abuse, need for vent or inotrope.

- Their best clinical decision tree model was 89% sensitive and 61% specific. It reduced the number of admissions by 27% while missing 2% of patients who needed hospitalization

- Independent risk factors requiring hospitalization: significant medical history, greater than 1 ALTE in 24hrs, male sex.

Take Home Points:

- Most common causes of ALTE are: GERD/choking, seizure, and respiratory infection

- Clinical gestalt for admitting ALTE patients is very sensitive, but at the expense of low specificity which drains hospital resources and potentially causes undue stress for families

- Decision making tools aimed at reducing admissions exist, but they are imperfect, and not universally used

- Summarization of standards for admission vs disposition are as follows.

- Admit if: symptomatic at time of evaluation (toxic, lethargic, recurrent vomiting, respiratory distress), suspected infection, bruising or other suspicion for abuse, prior ALTE (in pt or sibling), need of resuscitation by caregiver

- No admission if: first ALTE, brief, self-limited, and associated with feeding, providing now physiologic compromise at the time of evaluation

References:

- Mittal MK et al. A clinical decision rule to identify infants with apparent life-threatening event who can be safely discharged from the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2012; 28(7): 599-605. PMID: 22743742

- Kaji AH et al. Apparent life-threatening event: multi center prospective cohort study to develop a clinical decision rule for admission to the hospital. Ann Emerg Med 2013; 61(4): 379-87. PMID: 23026786

- Infantile apnea and home monitoring. NIH Consensus Statement Online. 1986; 6:1-10. Available at http://consensus.nih.gov/1986/1986InfantApneaMonitoring058html.htm (Accessed on September 15, 2015)

- Sarohia M and Platt S. Apparent Life-Threatening Events in Children: Practical Evaluation and Management. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract. 2014 Apr;11(4):1-14. PMID: 24834606

- Kiechl-Kohlendorfer U, Hof D, et al, Epidemiology of apparent life threatening events. Arch Dis Child. 2005 Mar;90(3):297-300. PMID: 15723922

- Esani N, Hodgman JE, Ehsani N, Hoppenbrouwers T. Apparent life-threatening events and sudden infant death syndrome: comparison of risk factors. J Pediatr. 2008 Mar;152(3):365-70. PMID: 18280841

- McGovern MC, Smith MB. Causes of apparent life threatening events in infants: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2004 Nov;89(11):1043-8. PMID: 15499062

- Orenstein SR. An overview of reflux-associated disorders in infants: apnea, laryngospasm, and aspiration. Am J Med. 2001 Dec 3;111 Suppl 8A:60S-63S. PMID: 11749927

- Gray C, Davies F, Molyneux E. Apparent life-threatening events presenting to a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999 Jun;15(3):195-9. PMID: 10389958

- Brand DA, Altman RL, Purtill K, Edwards KS. Yield of diagnostic testing in infants who have had an apparent life-threatening event. Pediatrics. 2005 Apr;115(4):885-93. PMID: 15805360

- Kant S, Fisher JD, Nelson DG, Khan S. Mortality after discharge in clinically stable infants admitted with a first-time apparent life-threatening event. Am J Emerg Med. 2013 Apr;31(4):730-3. PMID: 23399327

- American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on SIDS. The changing concept of sudden infant death syndrome: diagnostic coding shifts, controversies regarding the sleeping environment, and new variables to consider in reducing risk. Pediatrics. 2005 Nov;116(5):1245-55. PMID: 16216901

- Southall DP, Plunkett MC, et al. Covert video recordings of life-threatening child abuse: lessons for child protection. Pediatrics. 1997 Nov;100(5):735-60. PMID: 9346973

- Oren J, Kelly D, Shannon DC. Identification of a high-risk group for sudden infant death syndrome among infants who were resuscitated for sleep apnea. Pediatrics. 1986 Apr;77(4):495-9. PMID: 3960618

- Corwin MJ, et al. Apparent life threatening events in infants. In: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on September 15, 2015.)

One comment about your epidemiology section, I think an “ALTE requiring CPR” is by definition not an ALTE. May want to clarify there. Otherwise thanks for the great summary!

BRUE is the new ALTE now. A great website is the rch.org.au for paeds.