Author: Liete Eichorn

Editor: Sarah Fetterolf, MD

Background

- Chagas disease (CD), also called American trypanosomiasis, is a systemic infection caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi.

- Although the triatomine bug (or “kissing bug”) transmits most cases in endemic regions of Mexico, Central and South America, non-vector-borne transmission is also possible via ingestion of contaminated food, organ transplants or blood transfusion, sexual contact, and congenital infection.

- Designated a “neglected tropical disease” by the WHO since 2005, CD remains under-diagnosed with a global case detection rate less than 10%.

- In many countries, including the U.S., detection is closer to 1%.

- The CD case fatality rate varies by disease stage and subtype, from <5% in the acute phase to >75% with acute reactivation (usually in immunocompromised patients).

- Cure rates up to 100% are possible with early diagnosis and treatment.

- Globally, however, <1% of infected patients receive treatment.

- 20-40% of untreated chronically infected patients develop serious cardiac, digestive, or neurological dysfunction decades after initial exposure.

- Risk factors

- Living in or traveling to Latin America for any extended period

- Poverty

- Sleeping in mud, thatch, or adobe housing

- Prolonged close contact with animal reservoirs (opossums, raccoons)

- Being born to a seropositive mother

- Receiving a blood transfusion or organ transplant not screened for Chagas

- Sharing needles or engaging in risky sexual behavior with anyone infected with CD

Epidemiology

- An estimated 8 million people worldwide are infected with T. cruzi, with a majority concentrated in 21 endemic countries in Latin America.

- Rising immigration has increased CD prevalence in non-endemic areas in recent years

- 300,000 infected persons currently live in the U.S., including 57,000 Chagas cardiomyopathy patients and 43,000 infected reproductive-age women.

- Most U.S. cases are imported from Latin America

- Rare locally acquired vectorborne cases have been reported in the southern U.S.

- Because infection is typically lifelong, seroprevalence rises with age.

Clinical Presentation

Acute infection

- Usually asymptomatic or pauci-symptomatic with mild flu-like symptoms (fever, myalgia) lasting 8-12 weeks. Symptomatic acute infection is most common in children under 5.

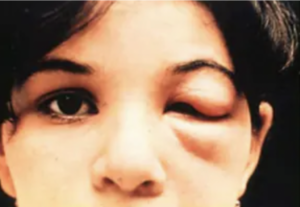

- <50% of patients develop a “chagoma” (swelling and inflammation at inoculation site) or the Romaña sign (unilateral bipalpebral chagoma, pathognomonic for Chagas when present, see image below):

- Generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly are also sometimes seen.

- <1% of patients present with high-grade parasitemia and life-threatening symptoms including myocarditis, pericardial effusion, meningoencephalitis, neuritis, or a combination of these. This presentation is often fatal and most common in immunocompromised patients and children under 2.

Chronic, indeterminate phase (latent, preclinical)

- Asymptomatic and can be lifelong if untreated.

- 20-40% progress to the chronic determinant phase.

Chronic, determinate phase

- Cardiac manifestations are most common (95% of chronic determinate cases), followed by colon (megacolon) and esophagus (megaesophagus) involvement. Neurological symptoms (neuritis, sensory impairment) also occur in up to 10% of patients.

- Gastrointestinal chronic Chagas

- Colon involvement: Constipation, abdominal pain, and distension are common symptoms.

- Esophageal involvement: Primary symptoms include dysphagia, odynophagia, and epigastric pain. Weight loss, cough, and regurgitation may also occur.

- Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy (CCC) presentation varies, but typically involves one or more of the following:

- Arrhythmias

- RBBB is often the first sign of CCC.

- Other typical findings include AV block (1st, 2nd, or 3rd degree), Afib, ventricular tachyarrhythmias (frequent PVCs, often polymorphic, and nonsustained VT), primary ST- and T-wave abnormalities, pathological Q waves, or electrically inactive areas, low voltage QRS, and sudden cardiac death

- Dilated cardiomyopathy with enlargement of all four chambers (typically visible on x-ray). LV global dysfunction, seen as reduced LVEF on echocardiogram.

- Thromboembolism, leading to stroke (more common) or PE (less common).

- Cardiac aneurysm, usually affecting the apical left ventricle.

- Cardiomegaly is an important predictor of mortality.

Acute reactivation (primarily seen in immunosuppressed patients)

- 20% – 40% of individuals co-infected with HIV and T. cruzi experience disease reactivation, with elevation of parasitemia to acute infection levels

- In HIV positive patients, the most common presentation is meningoencephalitis, with or without brain abscesses (CNS chagoma)

- May be confused with CNS toxoplasmosis

- Up to 100% mortality if untreated

- Acute myocarditis is seen in 10-55% of reactivation cases and can be superimposed on chronic cardiomyopathy

- Additional less-common presentations include cervicitis, gastrointestinal disease, peritonitis, and skin lesions (erythema nodosum)

Congenital infection

- 60-90% of congenitally acquired infections are clinically silent.

- Presentation varies in symptomatic infants, but may include low birthweight, prematurity, low Apgar scores, and hepatomegaly with or without splenomegaly.

- As with all other routes of transmission, approximately 30% of untreated congenitally infected individuals will progress to the symptomatic chronic determinate phase in adulthood.

Pathophysiology

- Transmission:

- T. Cruzi is a flagellated protozoan transmitted by the triatomine (reduviid) bug when it defecates on human skin. Trypomastigotes, the infectious form, are present in triatomine feces and enter their human host when rubbed into an open wound (ie. reduviid bug bite) or mucous membrane.

- Ingestion of food or drink contaminated with triatomine feces can also transmit disease. This typically results in a more severe presentation, fatal in up to 35% of cases.

- Replication within host cells and release into the bloodstream leads to parasitemia and infection of distant cells, preferentially in the heart and myenteric plexus.

- Bloodborne trypomastigotes differentiate into amastigotes within cells, which can lie dormant for decades.

- In the chronic indeterminate phase, trypomastigotes continue to circulate at levels that are usually too low to detect clinically, but high enough to spread infection.

- Asymptomatic patients can transmit disease through blood transmission, such as organ donation, blood donation, needle sharing, and sexual contact. Trypomastigotes are also able to cross the placental barrier, resulting in congenital infection.

- In acute reactivation, large numbers of amastigotes (the dormant form) differentiate back into trypomastigotes (the active form) and establish a parasitemia, comparable to that seen with acute infection.

- The pathophysiology of organ damage in the chronic determinate stage is not well understood, but thought to be a combination of direct tissue parasitism and immune autoreactivity.

- In the heart, chronic inflammation and fibrosis leads to segmental motility deficits and chamber dilation. This also disrupts the conduction system, resulting in arrhythmias.

- In the GI tract (ie. esophagus and colon), there is destruction of the myenteric plexus with loss of up to 95% of neurons.

Diagnostics

In symptomatic patients, diagnosis is mainly clinical with epidemiologic considerations (travel or migration) and laboratory confirmation (parasitology or serology). The most recent guidelines recommend serologic testing in individuals with epidemiologic risk factors plus any of the following:

- ECG abnormalities

- ie. Conduction abnormalities (such as bundle branch blocks, AV block), PVCs, low voltage QRS, bradyarrhythmias, tachyarrhythmias

- Regional wall motion abnormalities (particularly basal inferolateral, apical aneurysm)

- Thromboembolism (ie. Stroke, PE)

- Congestive heart failure and/or a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction

- Megacolon/megaesophagus

Laboratory tests

- Acute phase or acute reactivation – direct detection of parasites in blood (thick and thin blood smears + PCR)

- Chronic phase (indeterminate or determinate) – serology (via ELISA or IFA)

- Must use 2 tests that detect different antibodies against T. cruzi

- If results vary, use Western blot as tiebreaker

- In endemic areas, rapid diagnostics are available for point-of-care testing (fingerstick sample yields results within 1 hour). Performance is good in areas where pre-test probability is high, but varies by region.

Regardless of disease phase and/or symptoms, all who test positive for T. cruzi infection should receive:

- Electrocardiogram

- Echocardiogram

- Chest X-ray

Management/Treatment

Benznidazole and nifurtimox are currently the only antitrypanosomal drugs approved to treat CD

- Benznidazole (5 mg/kg per day in 2 divided doses for 60 days) is first line treatment because it is better tolerated in most people

- Contraindications – pregnancy, severe renal or liver dysfunction, disulfiram use within the last 2 weeks.

- In pregnancy, treatment should be started immediately after birth for both the mother and infant

- Despite being the standard of care, as of 2024, benznidazole is only FDA approved for pediatric use in patients ages 2-12 years. All other use is considered “off label”

The decision to treat hinges on disease stage and patient demographic:

- Acute stage (up to 90 days post inoculation), all ages – treat

- Chronic infection in all patients under 18 – treat

- Chronic infection in adults without organ damage (indeterminate phase) – treatment is suggested, but not required

- Early chronic phase, treatment preferable

- Late chronic, antiparasitics less effective; must weigh potential benefit against adverse medication side effects

- Exception: women of childbearing age – trypanocidal therapy recommended over no treatment due to risk of congenital transmission

- Chronic infection in adults with associated organ damage (determinate phase) – symptomatic/supportive treatment only; antiparasitics not recommended

- Admit and/or refer to specialist

- Acute reactivation (ie. in HIV) – anti-trypanosomal treatment urgently indicated

Managing chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy

- Evidence of the efficacy of specific therapies is limited.

- Current guidelines recommend treating according to standards of care for non-Chagas cardiomyopathy.

- One randomized control trial by showed that in patients with ventricular arrhythmias, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator plus amiodarone may reduce sudden cardiac death and CHF exacerbations/hospitalizations when compared with amiodarone alone.

Accessing anti-trypanosomal drugs in the U.S.

- For assistance with clinical management, contact CDC ([email protected]; 404-718-4745) or CDC emergency operator (770-488-7100)

- If you have further questions for treatment at your facility, make sure to contact infectious disease to get the patient started on the correct treatment and ensure close follow up.

Prophylaxis, Screening, and Disease Control

- There is currently no CD vaccine.

- Prophylactic antitrypanosomal treatment may be considered for transplant patients with CD due to risk of reactivation with immunosuppression, but evidence of benefit is limited.

- Disease control efforts have primarily centered around vector control and screening of donated blood and organs prior to transfusion or transplantation.

- The CDC recommends screening all women who have lived in Mexico, Central America, or South America before or during pregnancy. Barriers to achieving this goal include limited knowledge among U.S. medical providers of congenital Chagas infection and how to order testing.

- The Pan American Health Organization also recommends screening anyone who was born in or lived longer than 6 months in a country with endemic Chagas as well as travelers with confirmed exposure to triatomines

CD in the ED

Most patients presenting with Chagas will be unaware of their infection status.

Emergencies secondary to cardiac or GI dysfunction in the chronic determinate phase are most often seen, with the following acute complaints:

- Cardiac: chest pain, palpitations, recurrent syncopal episodes, dyspnea, sudden cardiac death

- Upper GI: dysphagia, coughing/choking, chest/epigastric pain

- Lower GI: constipation, meteorism, abdominal pain or distention

Other rarer presentations have been described in case reports:

- Acute CNS CD

- 56yo Hispanic male with lower extremity weakness, malaise, and difficulty voiding x 3 days, as well as fevers, chills, rash, nausea, and vomiting x 3 weeks

- Found to be HIV positive with a CD4 count of 50

- Multiple ring-enhancing lesions visualized on brain MRI, largest in the corpus callosum.

- After 3 days of empiric treatment for toxoplasmosis without improvement, brain biopsy was performed, confirming CD diagnosis. Nifurtimox treatment was initiated but continued decline of mental and respiratory status led to withdrawal of life support.

- 56yo Hispanic male with lower extremity weakness, malaise, and difficulty voiding x 3 days, as well as fevers, chills, rash, nausea, and vomiting x 3 weeks

- Acute CD reactivation in an immunosuppressed patient

- 49yo male 11 months post heart transplant presenting with palpitations and lightheadedness

- New right bundle branch block discovered on ECG

- Treatment: pacemaker and benznidazole, with improvement in conduction disease (75% reduction in ventricular pacing) after 1 month

- 49yo male 11 months post heart transplant presenting with palpitations and lightheadedness

- Acute CD after travel

- 53yo F returning from travel in Latin America with suspected orbital cellulitis, headache, and 102° fever

- Treatment with nifurtimox, the only drug available at CDC at the time, led to complete recovery

- 53yo F returning from travel in Latin America with suspected orbital cellulitis, headache, and 102° fever

Prognosis

- Clinical cure rate:

- 60-85% for patients treated in the acute phase

- >90% for infants treated in first year of life (up to 100% with early initiation)

- Approaches 0% with progression to chronic phase

- Prognosis worsens with progression to the chronic determinate phase.

- Non-trypanocidal treatment of CCC may improve survival.

- >75% of acute reactivations are fatal, due in part to late recognition by healthcare providers.

- Early antitrypanosomal therapy can be curative.

Sociocultural Considerations

- Associations between CD and low socioeconomic, rural populations has created a lasting social stigma against affected individuals.

- Physicians practicing in Latin America or engaging with patients from endemic areas should be aware of and sensitive to this stigma, which may affect patients’ willingness to report symptoms or seek care.

- Engaging in cultural sensitivity when delivering a diagnosis and evaluating or counseling patients fosters trust in the healthcare system, enhances treatment adherence, and improves patient health outcomes.

Take Home Points

- CD is a neglected tropical disease that causes significant morbidity and mortality across the Americas. Increased awareness of CD among healthcare providers and at-risk individuals is urgently needed.

- EDs in the U.S. are seeing increasing numbers of cardiac emergencies ultimately attributed to undiagnosed chronic Chagas.

- Consider Chagas in the setting of unexplained cardiomyopathy or gastrointestinal pathology (megaesophagus and megacolon), especially in adult Latin American migrants or travelers.

- Anti-trypanosomal treatment (benznidazole or nifurtimox) is indicated in adults in the acute or early chronic phase; all children and adolescents under age 18, regardless of phase; all immunocompromised individuals with disease reactivation; women of childbearing age, especially those who intend to become pregnant.

- For asymptomatic adults in late chronic indeterminant phase, weigh benefits of treatment against potential adverse effects on a case-by-case basis. In general, risk:benefit ratio worsens with age.

- Adults in the chronic determinate phase receive no benefit from antitrypanosomal treatment (organ damage irreversible at this point) and should instead be referred to an appropriate specialist for monitoring, supportive care, and/or surgery.

References

- Carter, Y. L., Juliano, J. J., Montgomery, S. P., & Qvarnstrom, Y. (2012). Acute Chagas disease in a returning traveler. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 87(6), 1038–1040. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0354

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Treatment of Chagas Disease. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/chagas/treatment/index.html

- Clark, E. H., & Bern, C. (2021). Chagas Disease in People with HIV: A Narrative Review. Tropical medicine and infectious disease, 6(4), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6040198

- Department of Health and Human Services. (2023) Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents With HIV. Retrieved from https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/chagas-disease

- Gali, W. L., Sarabanda, A. V., Baggio, J. M., Ferreira, L. G., Gomes, G. G., Marin-Neto, J. A., & Junqueira, L. F. (2014). Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for treatment of sustained ventricular arrhythmias in patients with Chagas’ heart disease: comparison with a control group treated with amiodarone alone. Europace : European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology : journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology, 16(5), 674–680. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eut422

- González-Tomé, M. I., López-Hortelano, M. G., & Fregonese, L. (2018). Challenges and opportunities in the vertical transmission of Chagas disease. Anales de Pediatría (English Edition), 88(3), 119–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anpede.2018.01.001

- Guhl, Felipe & Ramírez, Juan David. (2021). Poverty, Migration, and Chagas Disease. Current Tropical Medicine Reports. 8. 10.1007/s40475-020-00225-y.

- Irish, A., Whitman, J. D., Clark, E. H., Marcus, R., & Bern, C. (2022). Updated Estimates and Mapping for Prevalence of Chagas Disease among Adults, United States. Emerging infectious diseases, 28(7), 1313–1320. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2807.212221

- Kuehn, B. M. (2016). Chagas Heart Disease an Emerging Concern in the United States. Circulation, 134(12), 895–896. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024839

- Li, S. X., Soles, E. O., Sharma, P. S., & Rao, A. K. (2023). Case report: diagnosis of chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy using a multimodality imaging approach. European heart journal. Case reports, 7(1), ytac487. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcr/ytac487

- Lury, K. M., & Castillo, M. (2005). Chagas’ Disease Involving the Brain and Spinal Cord: MRI Findings. American Journal of Roentgenology, 185(2), 550–552. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.185.2.01850550

- Manne-Goehler, J., Reich, M. R., & Wirtz, V. J. (2015). Access to care for Chagas disease in the United States: a health systems analysis. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 93(1), 108–113. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.14-0826

- Marin-Neto, J. A., Rassi, A., & Simoes, M. V. (2023). Chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. UpToDate. Retrieved June 25, 2024 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/chronic-chagas-cardiomyopathy-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis/print

- Meymandi, S., Hernandez, S., Park, S., Sanchez, D. R., & Forsyth, C. (2018). Treatment of Chagas Disease in the United States. Current treatment options in infectious diseases, 10(3), 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40506-018-0170-z

- Montgomery, S., Roy, S., & Dubray, C. (2023). Trypanosomiasis, American / Chagas Disease | CDC Yellow Book 2024. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved June 22, 2024, from https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2024/infections-diseases/trypanosomiasis-american-chagas-disease

- Neeki, M. M., Park, M., Sandhu, K., Seiler, K., Toy, J., Rabiei, M., & Adigoupula, S. (2017). Chagas Disease-induced Sudden Cardiac Arrest. Clinical practice and cases in emergency medicine, 1(4), 354–358. https://doi.org/10.5811/cpcem.2017.5.33626

- Nunes, M. C. P., Beaton, A., Acquatella, H., Bern, C., Bolger, A. F., Echeverría, L. E., Dutra, W. O., Gascon, J., Morillo, C. A., Oliveira-Filho, J., Ribeiro, A. L. P., Marin-Neto, J. A., & American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Stroke Council (2018). Chagas Cardiomyopathy: An Update of Current Clinical Knowledge and Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 138(12), e169–e209. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000599

- Pan American Health Organization. (2018). Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Chagas disease. https://www.paho.org/en/documents/guidelines-diagnosis-and-treatment-chagas-disease

- Pecoul, B., Batista, C., Stobbaerts, E., Ribeiro, I., Vilasanjuan, R., Gascon, J., Pinazo, M. J., Moriana, S., Gold, S., Pereiro, A., Navarro, M., Torrico, F., Bottazzi, M. E., & Hotez, P. J. (2016). The BENEFIT Trial: Where Do We Go from Here?. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 10(2), e0004343. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004343

- Pinazo Delgado, M.-J., & Gascón, J. (Eds.). (2020). Chagas disease: A neglected tropical disease. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44054-1

- Rezende Filho, J., de Oliveira, E.C. (2020). Chronic Digestive Chagas Disease. In: Pinazo Delgado, MJ., Gascón, J. (eds) Chagas Disease. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44054-1_7

- Schweis, F., Aslam, S., Enciso, J. S., Adler, E., & Logan, C. (2018). Abstract 15466: Recurrent Reactivation of Chagas Disease After Cardiac Transplant Presenting as Acute Heart Block. Circulation, 138(Suppl_1), A15466–A15466. https://doi.org/10.1161/circ.138.suppl_1.15466

- Suárez, C., Nolder, D., García-Mingo, A., Moore, D. A. J., & Chiodini, P. L. (2022). Diagnosis and Clinical Management of Chagas Disease: An Increasing Challenge in Non-Endemic Areas. Research and reports in tropical medicine, 13, 25–40. https://doi.org/10.2147/RRTM.S278135

- Tucker, C. M., Marsiske, M., Rice, K. G., Nielson, J. J., & Herman, K. (2011). Patient-centered culturally sensitive health care: model testing and refinement. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 30(3), 342–350. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022967

- Vancini, R. L., Vancini-Campanharo, C. R., Andrade, M. S., Teixeira de Gois, A. F., & Barbosa de Lira, C. A. (2017). Patients with Chagas Disease and Cardiac Arrest Treated at the Emergency Department of a Reference Hospital in Brazil. Archives of Clinical Infectious Diseases, 12(3), e12504. https://doi.org/10.5812/archcid.12504

- Westjem. (2020, May 31). Chagas Disease-induced Sudden Cardiac Arrest. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. https://westjem.com/case-report/chagas-disease-induced-sudden-cardiac-arrest.html

- Wiltz, P. (2023). Identifying and Managing Vector-Borne Diseases in Migrants and Recent Travelers in the Emergency Department. Current Emergency and Hospital Medicine Reports, 11(2), 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40138-023-00265-4

- Yoshioka, K., Manne-Goehler, J., Maguire, J. H., & Reich, M. R. (2020). Access to Chagas disease treatment in the United States after the regulatory approval of benznidazole. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 14(6), e0008398. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008398